Ask any department chair, and most faculty, what the most vexing data point during the academic year is and the most likely answer would be “enrollments.” In a data-obsessed age when it seems everything is tracked and analyzed, few data points matter as much in higher education as enrollments. For many institutions, department funding is tied directly to enrollment numbers. Courses that don’t meet minimum enrollment requirements are canceled, snarling the distribution of teaching responsibilities among faculty and narrowing the intellectual range in the curriculum. Fluctuations in enrollments and majors—a close relative of enrollments data—are cited as reasons to create or cancel tenure lines. A lot is riding on what academic slang calls “butts in seats.”

A lot is riding on what academic slang calls “butts in seats.” Library of Congress/Thomas J. O’Halloran. Image cropped.

For the past several years, the AHA has conducted an optional annual enrollments survey of history departments. The inquiry, which asks participating departments to report enrollments for each of the previous four years, is the only available source that collects history-specific enrollments data from individual institutions. While not statistically representative of higher education as a whole, these data capture broad national trends. With the data’s limitations firmly in mind, we’re parsing this year’s survey in the context of wider efforts across the discipline and across the landscape of higher education to better articulate the value of studying history and the humanities.

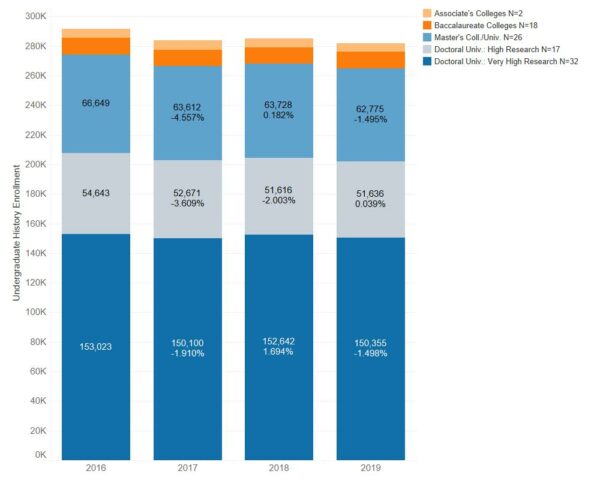

Undergraduate enrollment in history courses remained relatively stable in 2018–19, with a total decline of 1.1 percent from 2017–18 levels across the 104 US institutions that provided data to the AHA (Fig. 1). When responses from two Canadian institutions are included, the dip was just 0.8 percent overall. The four-year trends reported in our 2019 survey show a decline of 3.3 percent since the 2015–16 academic year. The modest change from 2017–18 reinforces the flattening trend we observed last year and is slightly lower than national declines in total undergraduate enrollment, according to recent data from the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center.1 Our enrollment survey corroborates a sense reported at many departments that the years of free-falling undergraduate enrollment may be behind them.

Fig. 1: Total enrollment change by year (US only).

Nevertheless, many faculty and administrators remain uneasy about the long-term downward slide of enrollments in history and other humanities disciplines. This is not a new area of concern, and much ink has already been spilled on these trends in the pages of Perspectives on History and other industry publications. The conventional wisdom on causation is well-known: the steady climb in tuition prices and the shock of the 2008–09 recession both drove students to “safe” majors that provided a clear first job after graduation; changes in general education requirements often have a negative impact on enrollments, for history and humanities departments in particular; and it is hard not to interpret declining enrollments as part of a larger devaluing of humanistic inquiry and expertise in American culture.

These and other pressure points were cited by respondents to the AHA’s 2019 survey, and it is clear that enrollments remain a major challenge for a discipline still struggling to recover from changes in higher education since the 2008–09 recession and from overall declines in national undergraduate enrollment. When asked to describe current conditions and recent changes in their enrollments or majors, institutions where enrollments have continued to decline cited several factors for the downward trend. Declining numbers of majors or overall enrollment decreases had predictably negative effects on department numbers. Respondents also cited structural conditions as causes for declines, such as state cuts to elementary and secondary education (and therefore fewer teacher-education students), the need to compete for students within revised general education requirements, students’ preference for subjects with clear pathways to employment, or a general institutional emphasis on science, technology, and health programs.

Undergraduate enrollment in history courses remained relatively stable in 2018–19.

Nonetheless, the AHA’s survey continues to identify strategies faculty can use, in conjunction with administrative partners, to address the lackluster trends. Respondents with stable or increasing enrollments described several concrete strategies to attract students. These included offering more online courses, hiring charismatic junior faculty members to teach new courses that students find exciting, and expanding departmental recruitment activities. In addition, successfully recruiting majors and minors, as might be expected, had a positive effect on overall enrollment.

Participants at the AHA’s annual Chairs’ Workshop regularly rank enrollments as one of the most important topics facing the discipline and use the workshop to share strategies to better market history courses to students, parents, administrators and colleagues in other disciplines. At this year’s workshop, chairs swapped stories of hosting regular “History Nights,” where faculty were invited to present talks relating their expertise to current events, or history students presented their capstone projects to a community audience. In addition to boosting enrollments, chairs reported that these activities also contributed to a sense of community within the department, as well as demonstrating the value of studying history.

Responses to the 2019 survey show large differences in the trajectory of enrollments at specific institutions.

Beyond its Chairs’ Workshop, the AHA has for many years endeavored to help departments increase their enrollments. In 2018, the AHA annual meeting featured a series of roundtables devoted to faculty strategies to increase enrollments.2 In January, the AHA will release a Department Toolkit, an online collection of resources produced primarily by the AHA and designed to help make the case for the value of studying history. In addition to tools designed to bolster enrollments and majors, and (dare we say it) to address graduates’ starting salaries, the resources in the Department Toolkit argue for the value of historical thinking in the broadest terms.

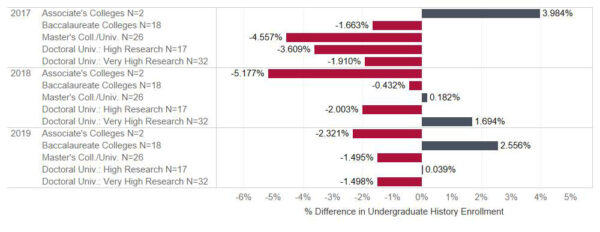

Strategies to market history courses vary, necessarily, by institutional circumstance. As in previous years, responses to the 2019 survey show large differences in the trajectory of enrollments at specific institutions. Fifty-five institutions reported stable or increasing undergraduate history enrollments, while 51 had declines. When responses are combined by basic Carnegie institutional type, only baccalaureate colleges and high-research doctoral universities were in positive territory over the past year (Fig. 2). The news might not be all bad, though: a recent reportby the Community College Research Center points to an increase in humanities enrollments at community colleges, of which only two are represented in the AHA survey respondents.3 (Though one must always be wary of a direct comparison of data at two-year and four-year colleges.)4 These divergent trends underscore the impact that department reforms and recruitment efforts, as well as local conditions, may be having on particular programs.

Fig. 2: Change in enrollment from previous year, by institution type (US only, N = 104).

Unfortunately, the number of departments responding to the 2019 survey was lower than in previous years. While the number of responses from universities offering master’s degrees was stable, and responses from baccalaureate colleges grew slightly, 21 fewer doctoral institutions provided data than last year, dropping from 70 to 49 institutions. Only two two-year colleges provided data, despite direct outreach to contacts at roughly 90 history and humanities programs. Despite this, respondents were still broadly representative of the higher education landscape as a whole. Together, they include over 1,100,000 undergraduate student enrollments over the past four years.

Moving forward, the AHA expects to offer an even more comprehensive picture of history enrollments at member departments. The association has begun asking for undergraduate enrollment data as part of program information for its annual institutional directory. This should mean less extra work for department faculty or staff who compile and report the data, and will increase the number of departments providing data, giving us an even larger window on trends in college history learning. In the meantime, the AHA will continue to conduct the annual enrollment survey and report on the findings, as well as continue to convene discussions on what departments can do to address the situation at their home institution and participate in the larger conversations on the value of history and higher education.

Notes

- Paul Fain, “College Enrollment Declines Continue,” Inside Higher Ed, May 30, 2019. [↩]

- Elizabeth Lehfeldt, “How Departments Are Tackling Lower Enrollments: Lessons from AHA18,” Perspectives on History, March 2018, https://www.historians.org/publications-and-directories/perspectives-on-history/march-2018/how-departments-are-tackling-lower-enrollments-lessons-from-aha18. [↩]

- Theo Pippins, Clive Belfield, and Thomas Bailey, “Humanities and Liberal Arts Education Across America’s Colleges: How Much Is There?” Community College Research Center, June 2019. [↩]

- Matt Reed, “Yes, But: Humanities at Community Colleges,” Inside Higher Ed, June 20, 2019. [↩]

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.