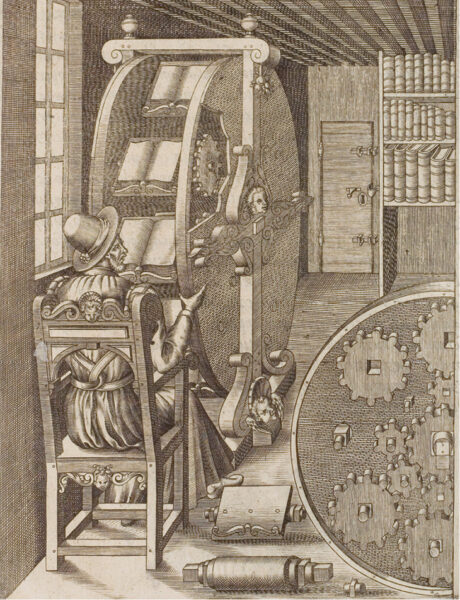

Bookwheel, from Agostino Ramelli’s Le diverse et artifiose machine, 1588.

As I read the literature on scholarly communication, participate in conversations about the changing nature of publishing, and build on my knowledge of important developments in open access policy and digital technology, I notice a recurring theme. One of the things that the rapid changes through which we are living is making clear is the importance of engagement; while the communication of ideas has always been at the core of what scholars do, the burgeoning of means for doing so has brought into focus the ways in which we engage the various audiences, collaborators, and contributors to our work. The stereotype of the humanities as a domain populated by scholars producing arcana entirely on their own is belied by the importance of the interactions we generate with other scholars, students, and audiences beyond the academy.

The ongoing conversation that is generated by publications written and peer reviewed by scholars working in a given field is what advances the discourse. The formats in which this happens can vary, while the need for the systems to evaluate and disseminate the knowledge remains. But it is also clear that there are still many questions that need to be answered as we chart the way forward for the discipline. Some of the big ones include: Can digital formats support the kind of sustained argument that historians expect from scholarly productions? What structures and training need to be in place that will allow scholars to utilize new means of presenting our scholarship? How can we, as a discipline, take advantage of these new environments to broaden our approaches to history and have that work properly counted toward professional credit?

The wider society in which we work has embraced digital means for presenting and obtaining information and knowledge, and most of us are ecumenical in the reading we do to be informed citizens. While scholarly communication has its own requirements it is vital that we remain open to new forms of communication where it’s potentially beneficial.

The four articles in this forum present a range of views on the changing nature of scholarly communication in history, and in particular the role of books in our discipline. The common thread that runs through all of the articles is the authors’ recognition of the importance of books while displaying an openness to new possibilities. Each represents an attempt to explore important issues such as discovery, peer review, book production, and the research process, and to think about the role played by monographic scholarship as the discipline and the academy changes.

Historians were writing books long before there was a tenure system, and they will continue to do so despite the changes that are expanding the possibilities for engagement. We must continue to further explore different means for communicating our knowledge, while ensuring that we don’t lose what’s valuable about books and the methods of engagement that the discipline has developed over time.

Forum: History as a Book Discipline

This article is part of the History as a Book Discipline forum. To read the other articles in the forum, see the links below:

- An Introduction by Seth Denbo

- The Opportunity Costs of Remaining a Book Discipline by Lara Putnam

- Is Digital Publishing Killing Books? by Claire Bond Potter

- Dissertations Are Not Books by Fredrika J. Teute

- The Changing Forms of History by Timothy J. Gilfoyle

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.