On planet MOOC—massive open online course—people have funny diets. Check out the menu of offerings at the restaurant called “Coursera.” The choice is almost limitless if you like the meat of science and engineering. But if you like seafood (the social sciences), the options get scarcer. It’s even slimmer pickings for a humanist-vegetarian. For now, the rapidly expanding planet is mainly a haven for carnivores. My course, A History of the World since 1300, was one of the outliers. Humanists interested in this kind of teaching will have to figure out how to adapt MOOCs, which are more hospitable to carnivores, to their own needs. At the same time, MOOCs can potentially help us reimagine teaching in the humanities.

Last spring, Princeton University became one of the founding members of Coursera, a partnership between 33 universities and an entrepreneurial private corporation, and agreed to launch a few pilot courses, among them a gateway in the History Department. Each course would be made freely available online to anyone in the world who wished to sign up—though only students at the university would receive credit.

What I learned grew out of the simultaneous challenge of teaching a course of vast scope on a vast scale. In the end, 50 Princeton undergraduates joined 93,000 students enrolled in the online course, an estimated 60 percent of whom were from outside the United States, and yielded over one million streaming views of my lectures and over 800,000 downloads.

Two principal motivations shaped my interest in teaching a MOOC. The first was to challenge my Princeton students to consider how the rest of the world thinks about the world. An important feature of this survey is to invite students to understand that the very same process—in this case the different stages or forms of what we call globalization—can mean different things to different peoples and different regions. What better way to see how this works than to engage people from around the world in debates over the very lectures that Princeton students ingest?

The second goal was to “flip the classroom”—to prerecord my lectures (24 in all) so that I could focus pedagogical energies on interactive components of the course. Students could thereby watch the lectures at any time during the week at their convenience, in the library, in a café, in the shower. But I also set fixed weekly times for precepts—discussions of preselected readings—and “Global Dialogues,” in which a guest would join me in a conversation with students. I served breakfast at 8:30 in the hallway outside the classroom; afterwards, we’d all go in and talk for 45 minutes about China and the world (with Benjamin Elman), Gandhi and Indian history (with Gyan Prakash), the Mediterranean (with Molly Greene and Anthony Grafton), Britain and the world (with Linda Colley), and so forth.

These Global Dialogues aimed to provide an interface between Princeton students and worldwide students. First, online threads asked Coursera students to presubmit questions for the guest, allowing Princeton students to hear how folks around the world framed historical problems. These conversations were recorded, edited, and then posted on the Coursera platform for the rest of the world to watch and discuss in online forums. Princeton students could thereby see how the rest of the world debated the conversations in which they participated.

Unlike most MOOCs, which are tailored for the online audience, this course is a Princeton course and designed to bring the world to Princeton and vice versa. It is an experiment in learning world history globally.

The first development phase of the course focused on the lectures and assignments. Flipping the classroom absorbed many months because lectures had to be prerecorded before the semester began. It’s not easy to lecture for so many hours to a black box with a blinking red light when you are accustomed to drawing upon the energy (or sleepiness) of students to cue you. Just getting accustomed to the ecosystem of the recording studio, the different dynamic relationship with PowerPoint images (which is one of the pluses of a recorded lecture and invite us to think more creatively about visuals of teaching), and segmenting lectures with embedded quizzes every 12 minutes or so required rewriting all my lectures and much time in the studio. This brings me to two major lessons learned while teaching this course.

Lesson One: Have a team. Preparing lectures is not just a matter of taking your normal, solo performances and recording them; the standard “sage on the stage” undergoes important changes once she or he steps behind a camera. If you are considering flipping the classroom, set aside time and secure a team; I had fabulous graduate assistants, invaluable help from our teaching and learning center, film editors, and an associate dean of the college upon whose shoulder I could weep. In the sciences, where more performed delivery goes on behind screens of equations and graphs, it is easier to produce videos. But if administrators do not put the capacity and resources behind their humanities teachers to produce discipline-appropriate courses for the web, planet MOOC will remain a haven for carnivores.

This development phase also involved designing assignments and an assessment scheme for Coursera students; there is no way I or my graduate students could evaluate thousands of papers. How to evaluate on scale? This is how it worked. The gist of the course for Princeton students (weekly readings, papers, exams) did not change. For Coursera, I assigned fortnightly papers of 750 words each to be peer-reviewed. Any student who completed a paper by the due date was expected to assess five papers submitted by classmates. They had a week to write a paper and a week to assess their peers. In the end, 1,963 discrete “users” submitted over 5,000 essays and participated in almost 30,000 evaluations. All this also required a team.

Lesson Two: Think about your objectives. Before this experiment, I used to focus more on what I was teaching than what students were learning. But once I had to consider how students themselves would peer-assess, I became mindful of what they had to learn as a condition for evaluation. The course required that students learn how to evaluate each other and themselves; in the course of writing and conducting evaluations they were expected to explore the art of thinking historically. Learning how to evaluate meant being clear about what and how to evaluate so that students could gauge their own development by tracking how they became better at mastering the variables we asked them to assess (in this case, the use of evidence, the logic of the argument, and exposition).

The depth of the challenge became clear only as the course unfolded—I watched Coursera students from the Ukraine to Uruguay valiantly submit essays and then evaluate each other, discovering how thinking historically is more than mastery of content—it includes developing methods of analytical thinking. Of course, discovering this as the course marched through its paces meant scrambling and improvising, and helping where I could. Next time around, I will bring the wisdom of hindsight to bear at the outset.

Both lessons stem from the challenge of designing of an open online course in an interpretive discipline like history. Far more time goes into production than simply uploading lectures. This is because learning an interpretive discipline implies skills that require a different kind of interactivity that is not reducible to problem-solving knowledge. Some critics say that this makes the humanities more immune to scalable economies; I am not so sure. But what I now know from experience is that good humanities teaching on a large scale has to be conscious of the distinctive epistemic properties of the disciplines.

Did the course live up to hopes? Partly. But it was an experiment and will require reiteration to reach its full learning potential. There were snafus all over the place (spelling errors on slides, irritating mistakes in my delivery, and so forth).

Where it stumbled was where I had hoped that it would break new ground: the possibility of enhanced, global interactivity. From the perspective of Princeton students, participating in inter-visible conversations with Coursera students was never baked into the course expectations; it was entirely voluntary, a bonus. Only in the process did I come to recognize this was a design flaw.

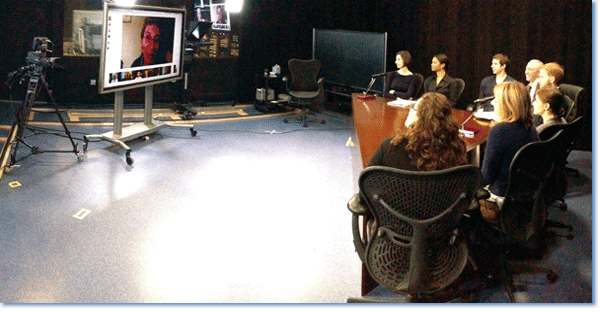

One solution: improvise. In the closing weeks of the course, for instance, I experimented with a couple of global classes, in which six Princeton and six Coursera students (from India, Italy, the Congo, etc.) convened in a Google Hangout to talk about topics in world history (Fig. 1). This pulled the veil back on the limits and possibilities of web technologies for global learning.

Figure 1. Princeton students meet Coursera students in a Google Hangout to discuss a recent lesson. Photo by and courtesy of Jeffrey Himpele.

The development of the course now goes into its second phase to emphasize the meaning and format of web-based interactivity. Next year, I will focus the inter-visibility of the Princeton and Coursera worlds. For instance, Princeton students will be expected to engage in dialogues across borders, place the results of these exchanges in their coursework, and be evaluated accordingly.

For Coursera students, peer assessment needs upfront tutoring. It is not a natural skill; it cannot develop organically within the timeframe of an accelerated 12-week semester without frustration and attrition. With time, students did learn to evaluate each other, and by the end many students did feel they had gained from the exercise of writing and assessing six essays. But there was too much stumbling around in the dark as I learned along the way.

In sum, there is enormous thirst for learning beyond our citadels. This thirst transcends national boundaries. The end of the course brought a tide of gratitude from all over the planet for the access that learners had to what was once so exclusive.

I’ll end, then, with a question that MOOC teaching left me: what is the future role of the university’s commitment to society as the ramparts around our institutions are being torn down? Centuries ago, the walls of the medieval university, defined as a sanctuary of knowledge, began to crumble. One might wonder whether and how the Internet has simply accelerated an ongoing process, and what this spells for the future of history.

Jeremy Adelman is the Walter Samuel III Professor of Spanish Civilization and Culture and director of the Council for International Teaching and Research at Princeton University. His most recent book is Worldly Philosopher: The Odyssey of Albert O. Hirschman(Princeton Univ. Press, 2013).

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.