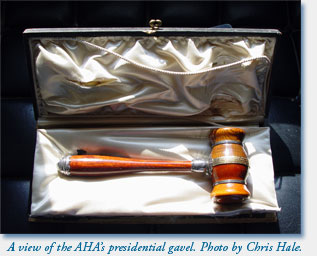

I muffed my first official act as president of the AHA. When outgoing president Gabrielle Spiegel handed me the gavel at the end of the business meeting on January 4, 2009, I quickly pounded it on the table and adjourned the meeting. At that point, the parliamentarian turned to me and said, kindly, “First, you were supposed to ask if there was any new business.” Like Chief Justice Roberts, I had forgotten the script. Fortunately, nobody asked me to do it again.

I muffed my first official act as president of the AHA. When outgoing president Gabrielle Spiegel handed me the gavel at the end of the business meeting on January 4, 2009, I quickly pounded it on the table and adjourned the meeting. At that point, the parliamentarian turned to me and said, kindly, “First, you were supposed to ask if there was any new business.” Like Chief Justice Roberts, I had forgotten the script. Fortunately, nobody asked me to do it again.

Each year since 1899, the elaborately engraved AHA gavel has facilitated the transfer of authority from one president to the next. Frederick Jackson Turner passed the gavel to his successor in 1910, just as Arthur M. Schlesinger did in 1942 and James McPherson in 2003. I have no idea whether anyone before me altered the script, though in 2005 Linda Kerber clearly got the ritual right. According to Perspectives, she accepted the gavel, “and noting there was no further business . . . declared the meeting adjourned.” A few years earlier a caption-writer for Perspectives added a little drama to the ceremony by writing: “Wm. Roger Louis passes the torch to 2002 president Lynn Hunt.” You will be relieved to know that the object in their hands was a gavel.

The AHA torch is metaphorical. The gavel is real. A band of gold encircling its head bears the following inscription:

This gavel is presented to the American Historical Association by Samuel Macauley Jackson, Boston December 28, 1899. It is made of the five following woods, four of which forming the head consist of the maple of Conn. The ash of Penn. The red birch of NH. And the oak of NY State. The gold band upon which this is engraved is from Cal. Upon the two silver bands are the words “From Nevada”. The handle is made of the vermilion of Kentucky. Tiffany 18k Solid Gold.

The inscription offers both information and symbolism.

Because I teach and write about artifacts as historical sources, I have been puzzling over the AHA gavel, trying to connect what I could learn about its provenance and attributes with the larger history of voluntary societies in the 19th century. I have also wondered what the gavel might tell me as incoming president of the AHA. In that regard three themes stand out.

For me, the provenance of the AHA gavel is a reminder that from the very beginning, the AHA was sustained by its affiliates. When Samuel Macauley Jackson presented the Tiffany, he was secretary of the American Society for Church History, an office listed alongside the roster of AHA officers on the opening page of that year’s Proceedings. The relationship between the AHA and its affiliates has taken different forms over the years, but the link between the umbrella organization and its subgroups endures. Assessing and improving those relationships is in fact one of the tasks that the Council has set for itself in the coming year. This is not only an issue for those groups formally designated as affiliates, but also for the many subgroups and committees that allow a very large organization to address the needs of its members. Toward that end, the Council has established two new task forces, one focused on strengthening our commitment to community college and K–12 teachers, and the other to address GLBTQ issues—the latter having been proposed long before anybody proposed boycotting a hotel in San Diego.

Second, the AHA gavel reminds me of the geographic reach of the association. Although wood and metal from seven states hardly represented the full membership of the Association even in 1899, the mixture of materials did suggests the expansiveness of history, a theme we are building on in the 2010 convention. The conference theme, “Islands, Oceans, Continents,” is meant to suggest literal and metaphorical spaces. How do we as historians consider the intersection of geography, politics, and culture—within and beyond our organization?

Finally, the AHA gavel intrigues me in part because there is much more to be learned about it. The gavel offers another gift—a historical puzzle. Over the past few weeks I have been surfing the internet, delving into odd volumes in the library, and frantically e-mailing experts in many fields, to see if I could establish some sort of context for Jackson’s gift. I have learned enough to know that there is more to discover, but for what it is worth, here are my conclusions.

Gavels belong to a broader category of common objects used to signify authority. Think of the Woolsack in the British House of Lords. Or the miniature oars employed in Admiralty Courts in colonial British America. A gavel is a stylized version of the mallets or hammers used in the building trades, and is appropriated by Freemasons as insignia of apprenticeship or mastery. George Washington used a Masonic gavel in laying the cornerstone for the U.S. Capitol in 1793. His gavel, embellished in 1856 with a silver disc giving its provenance, is now owned by a Lodge in the District of Columbia. It has a slight peak on one edge, signifying the mallet used by real masons to break up stone.1 In contrast, the supposed gavel used in the U.S. Senate is really a kind of knocker. It has no handle and, I suspect, was never intended to represent a hammer. Made of natural ivory, it is shaped like an hour glass. No one is quite certain when it was first used, though by the 1830s, some people associated it with Thomas Jefferson. There was apparently no gavel at the Continental Congress or in any representative body in the early years of the Republic. Some remembered John Adams calling the Senate to order by tapping on his water glass.

The gavels in use today appear to have derived from what Arthur M. Schlesinger called the “passion for associational activity” that developed in the 19th century. In his 1942 AHA Presidential Address, Schlesinger quoted the humorist Will Rogers: “Why, two Americans can’t meet on the street without one banging a gavel and calling the other to order.”2 Neither scepter nor mace, a gavel relies for its power on respect for the ongoing flow of leadership in participatory gatherings. It is useful for managing a fractious meeting, but only if those present are willing to honor its call.

By the end of the 19th century, the presentation of gavels had become a way of asserting the power of constituent groups within a body. At the Democratic National Convention held in Chicago in 1892, a man representing “the zinc producers and miners of Missouri” claimed the floor in order to present the presiding officer with a gavel, “not made of tin nor stolen from a Nebraska homestead, but mined and made in Jasper County, Missouri, and bearing the inscription, ‘We need no protection.’” In this case, the gavel made its own argument against a hated tariff.3

In the late 19th century, gavels also became repositories of historical memory. At a gathering of Civil War veterans at Council Bluffs, Iowa, in 1894, someone presented the presiding officer with a gavel made from wood cut “from a spot near where the gallant and chivalrous General McPherson fell.” Praising the boys in blue, the speaker added a not-so-gracious allusion to “the Negro mule-drivers in the rear.”4 At the annual convention of the Master Car and Locomotive Painters, a man the presiding officer called “plain Sam Brown” presented the association “a gavel made out of a piece of wood taken from the U.S. Flagship Olympia, which made such a memorable record for the United States on May 1, 1898, at Manila Bay.” He explained that he had received the wood from an officer at the Charlestown, Massachusetts, navy yard, where the Olympia had come for repairs.5

So when Samuel Macauley Jackson presented the Tiffany gavel to the American Historical Association, he was building on a long and broad tradition. Like the zinc gavel presented to the Democratic National Convention a few years before, it could also have been a reminder of the importance of a large and, perhaps in his view, neglected affiliate. Those better versed than I in the history of the AHA may have more to say about that, but it is probably worth noting that the Society for Church History does not itself have a gavel.

A full history of the gavel requires an exploration of Tiffany’s role in its construction. I do not know whether Jackson commissioned an item composed of particular metals and woods or whether this was something the manufacturer had on hand. There is, however, a bit of a puzzle in the inscription. Note that it mentions five woods, listing the four woods used in the head (maple from Connecticut, ash from Pennsylvania, red birch from New Hampshire, and oak from New York state), then adding after the reference to California gold and Nevada silver, that the handle of the gavel was made from “the vermilion of Kentucky.” Vermilion is a color, not a wood. So what kind of material actually came from Kentucky?

In an attempt to answer this question, I consulted a reference librarian at the Kentucky Historical Society, two experts on Kentucky folklore, a Harvard bibliographer, and a museum curator, four of whom joined me in a search on Google. Several of us found a reference to a wood called “vermillion” (with two l’s) that came from Papua New Guinea. None of us came up with a reference to Kentucky “vermilion.” Yet surely there must have been a wood with that name, unless the engraver left out a word and vermilion was simply an adjective. One of my consultants thought it referred to red oak. Another suggested the Kentucky Coffee Tree. Although actually a legume rather than a tree, this plant, now the official state tree, was highly valued in the early days. George Washington apparently had a specimen on his estate. According to the Kentucky State Library, its wood was prized “for its rich color and dense grain.” It was sometimes called “Kentucky Mahogany.”6 If anybody reading this essay has a better answer, please let me know!

The AHA gavel is a reminder of the complexity of seemingly simple things. In its slim frame, voluntarism, craft, economy, environment, politics, and historical memory come together inviting us to acknowledge both the geographical breadth and the methodological depth of our enterprise. Sometimes I imagine carrying the AHA gavel to Antiques Roadshow. The camera would zoom in on its polished surface, while the interviewer asked, “And what do you think it is worth?”

I would tell him that in 1984, it was appraised at $1,800. He would pause for dramatic effect, and then say: “Today, if it should come up for action, I would estimate its value at . . . “

I would gasp, and then say, “We do not plan to sell it.”

Notes

- For a photograph, see www.potomac5.org/gavel.php. [↩]

- Arthur M. Schlesinger, “What Then Is the American, This New Man?” AHA Presidential Address, 1942. American Historical Review 48:2 (January 1943), 225–244. [↩]

- Official Proceedings of the National Democratic Convention (Chicago: 1892) p. 68. [↩]

- Report of The Proceedings of the Society of the Army of Tennessee, (Cincinnati: 1895), p. 20. [↩]

- Proceedings of the 36th Annual Convention of the Master Car and Locomotive Painters’ Association (Chicago: 1904), p. 26. [↩]

- “Kentucky’s State Tree,” Kentucky Department for Library and Archives. [↩]