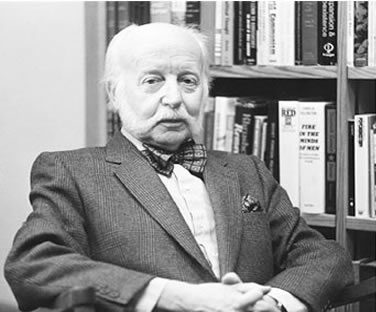

Gordon Craig, AHA President 1982. Photo courtesy Chuck Painter/Stanford News Service

Gordon Alexander Craig was born in Glasgow on November 26, 1913. His family emigrated to Canada and in 1925 moved to New Jersey. Craig attended public schools in Toronto, Ontario, and Jersey City; he graduated from Princeton University in 1936, received a BLitt from Oxford in 1938, an MA from Princeton in 1939, and a PhD in 1941.

In the summer of 1935, Craig toured Germany with a group of Princeton undergraduates. His keen observations of the Nazi regime, then just two years in power, began an engagement with the “German question” that would last for seven decades. Craig’s trip to Germany also had a more direct and immediate impact on his future: a chance meeting with a Rhodes scholar led him to apply for a scholarship, which, much to his surprise, he won. He arrived at Balliol College in the fall of 1936 to spend two of the most important years of his life. In Oxford, Craig studied with B. H. Sumner and E. L. Woodward, two of Britain’s finest historians, deepened his knowledge of European affairs, and watched from a ringside seat the preliminary bouts for the new world war that everyone expected. In 1938, Craig returned to Princeton, where he completed his doctoral dissertation a few months before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. After working in the Office of Strategic Services, he joined the Marine Corps and served in the South Pacific.

After the war, Craig taught at Princeton until 1961 when he moved to Stanford; from 1969 until his retirement 10 years later he was the J. E. Wallace Sterling Professor of Humanities. At both Princeton and Stanford, Craig was extraordinarily successful in the classroom. Beautifully written and flawlessly delivered, his lectures introduced generations of students to the drama of European history. He had a distinguished group of doctoral students, many of whom went on to be leaders of the profession: at the time of his death, the president and executive secretary of the German Studies Association, and the editor of theGerman Studies Review all had received their PhDs under his direction.

Craig’s scholarship was distinguished by both depth and breadth. He first made his reputation as a historian of diplomacy and military affairs. Two collections that he co-edited, The Makers of Modern Strategy (1943) and The Diplomats, 1919–1939 (1953), instantly become standard works in the field. His first book, The Politics of the Prussian Army, 1640–1945 (1955), remains a classic, still worth reading a half century after its publication. Craig’s best known works are his Germany, 1866–1945 (1978), a volume in the Oxford History of Modern Europe, and The Germans (1982), a brilliantly written record of the author’s enduring fascination with German politics and culture. Craig also published books on the battle of Königgrätz, the end of Prussia, Zürich in the 19th century, and the great German novelist, Theodor Fontane. There are three collections of his essays: War, Politics, and Diplomacy (1966), The Politics of the Unpolitical: German Writers and the Problem of Power, 1770–1871 (1995), and Politics and Culture in Modern Germany: Essays from the New York Review of Books (1999). Throughout his long and remarkably productive scholarly career, Craig wrote on a variety of topics but returned again and again to the question he had first confronted in 1935: how could a country like Germany, apparently so civilized and culturally creative, become the source of unparalleled misery and destruction?

Beginning with his selection as valedictorian of his Princeton graduating class, Craig received an unbroken chain of awards and honors. He had four honorary degrees, including one from the Free University of Berlin. He was an honorary fellow of Balliol College and a member of the British Academy, the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, and the Orden Pour le Mérite für Wissenschaften und Künste. He held a Commander’s Cross of the Legion of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany, the Goethe Medaille of the Goethe Gesellschaft, the Historikerpreis of the city of Münster, and the Benjamin Franklin-Wilhelm von Humboldt Prize. He was elected president of the American Historical Association in 1982 and served as vice president of the Comité International des Sciences Historique from 1975 to 1985.

Although Craig was long admired as a scholar and teacher, in the last two decades of his career he became increasingly well known as a public intellectual. He regularly reviewed works on European and German history for the New York Review of Books. In Germany, where his books were best sellers, he became something of a celebrity, widely sought after as a lecturer and the subject of several magazine articles and television interviews.

For more than 60 years, Craig kept a diary, now available in the Stanford University library, in which he recorded a life of extraordinary commitment and accomplishment. In addition to the pleasures of family and friendship, the daily entries describe Craig’s travels, the books he read or rediscovered, his experiences as a teacher, research projects, lectures, university politics, and government service. Plans to publish an edited version of this extraordinary document are now underway.

Craig remained intellectually engaged until the final months of his life, when first his eyesight and then his heart failed. He endured the infirmities of age and the burdens of declining health with remarkable grace and fortitude—this was a master teacher’s final lesson to those who watched the slow dying of his light.

Gordon Craig died on October 30, 2005, in Portola Valley, California. He is survived by his wife of 66 years, Phyllis Halcomb Craig; his daughters, the Reverend Susan Craig, Dr. Deborah Preston, and Professor Martha Craig; a son, Charles Craig; eight grandchildren; and two great-grandchildren.