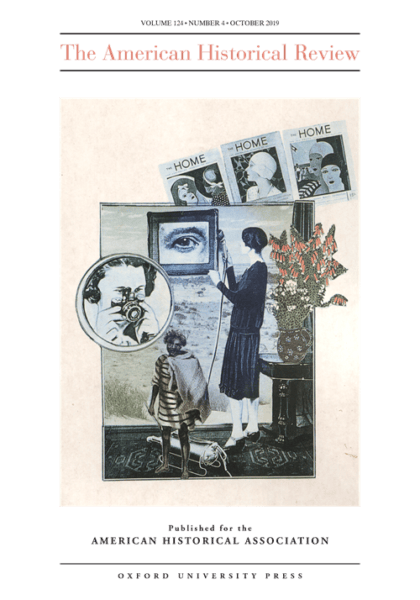

Collage no. 3 from the 1987–88 art installation Margaret and Sidney Go to the Pictures, by Australian artist Valerie Tring. As reproduced on a promotional postcard, the artwork challenges the viewer to reflect upon the historical dynamics of modernity, colonialism, and power that continue to play out in domestic space. The contributors to the roundtable in this issue, “Rethinking Domesticity,” similarly challenge readers to interrogate domesticity as both a historical and historiographical construct. The essays unsettle the notion that “modern” ideas about home life were static and easily translated, or that they affected individuals in consistent ways. The roundtable discussion seeks to reinvent, reimagine, and reclaim domesticity as a historical lens that reveals the intersections of empire, race, nationalism, citizenship, gender, class, and everyday life.

I think it would be fair to call the October American Historical Review the “Nuclear Issue.” The lead article, “Anticipating Armageddon: Nuclear Risk and the Neoliberal Sensibility in Thatcher’s Britain,” by Ellen Boucher (Amherst Coll.), reexamines popular anxieties about nuclear annihilation in late Cold War Britain. Rather than understanding this moment as one defined by “fear,” Boucher shifts our attention to discussions of “risk.” In Thatcherite Britain, she argues, the British state and public sought to cope with the potential threat of nuclear war by seeking ways to manage—and privatize—risk, often in concert with neoliberal ideals of self-reliance and state abdication from the public sphere. If Thatcher famously proclaimed, “There is no such thing as society,” the possible vaporization of this nonexistent construct in a nuclear blast accordingly became a matter for individual rather than collective apprehension.

Boucher’s concern with preparing for nuclear warfare as a form of risk management dovetails nicely with two other features, both of which address the history of civilian nuclear disasters. In response to the recent widely watched HBO miniseries Chernobyl, three scholars of nuclear disaster offer their evaluation of this made-for-TV history of the 1986 Soviet nuclear accident. Kate Brown (MIT), Yuliya Komska (Dartmouth Coll.), and Alex Wellerstein (Stevens Inst. of Technology) all find Chernobyl’s much-vaunted claims to historical accuracy severely overblown, even while they consider the important role televisual culture plays in shaping historical consciousness of recent events. Supplementing this, our regular “History Unclassified” section includes an account of the 2011 earthquake-induced Fukushima nuclear disaster written not by a historian, but by physicist and materials scientist Harry Bernas (Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique). In his highly personal essay, “The Trail from Fukushima,” Bernas argues that the meltdown was less an “unexpected catastrophe” than a result of all-too-predictable human fallibility and hubris rooted in history.

Three scholars all find Chernobyl’s much-vaunted claims to historical accuracy severely overblown.

October’s roundtable, “Rethinking Domesticity,” also touches on the “nuclear,” albeit in the sphere of the modern familial home rather than the physics laboratory. Conceived by Annelise Heinz (Univ. of Oregon) and Elizabeth LaCouture (Univ. of Hong Kong), and honed at workshops at the AHA annual meeting and the Berkshire Conference, the seven essays in the roundtable seek, in the conveners’ words, “to unsettle the historiographical legacy of domesticity as a category of analysis.” This effort brings together scholars of gender, the domestic sphere, and the family working across a wide array of fields in the 18th through 20th centuries. Kathryn Kish Sklar (Binghamton Univ., SUNY) introduces the roundtable with an essay that revisits her own classic work on Catharine Beecher and the “cult of domesticity” through the lens of imperial expansion and postcolonial categories of analysis applied to settler societies—relatively undeveloped fields in women’s history when she first published her Beecher biography over four decades ago.

Essays by LaCouture, Abigail McGowan (Univ. of Vermont), and Victoria Haskins (Univ. of Newcastle) do much the same thing for 19th-century China, colonial India, and indigenous peoples in the United States and Australia. LaCouture, for example, describes how the very concept of “domesticity” does little to illuminate the historical reality of women and the household during China’s encounters with modernity. She concludes, “The history of translating ‘domesticity’ into Chinese . . . reveals that Euro-American historiographical terms that were once thought to be universal map poorly onto other places and suggests that we need more inclusive frames for comparative gender history.” McGowan, in her gendered analysis of the material possessions and social arrangement of space inside aspirant bourgeois homes in late colonial India, shows how the creation of physical domestic interiors deployed caste hierarchies to articulate definitions of proper home life in a colonial context. And Haskins, comparing the fates of indigenous young women placed in white homes as servants in the United States and Australia, shows how state intervention not only helped to define domesticity, but could be integral to the formation of the modern settler colonial nation in its claims to civilizing authority. Yet Haskins also notes that colonial domesticity could have multiple effects. By demanding demonstrations of domesticity from female employers of domestic labor, the settler state sought to “perfect” white as well as indigenous women.

State intervention not only helped to define domesticity, it could also be integral to the formation of the modern settler colonial nation.

In a more traditionally “metropolitan” vein, the essays by Heinz and Julie Hardwick (Univ. of Texas, Austin) reflect the historical narrative that typically frames the rise and fall of domesticity, from early industrialization to postindustrial Europe and the United States. In her essay on Old Regime France, Hardwick describes the emergent domestic regime as “fractured.” By focusing on a single Lyonnaise household, Hardwick shows how domestic life and gender relations were both inextricably tied to the perils and promises of commerce for individual households in an unpredictable global economy and yet profoundly shaped by local familial practice. For her part, Heinz critically examines the role of the leisure-time “women’s” game, mahjong, as a crucial element in the making and marking of domestic space in mid-century Jewish American middle-class households. Commonly derided as an element of hegemonic domesticity, the ritualized playing of mahjong, Heinz suggests, could also represent a temporary reallocation of household labor and the understanding of domestic space.

The roundtable concludes with a comment by Antoinette Burton (Univ. of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign), a scholar who has done as much as anyone to re-center gendered histories around questions of empire and colonial ideology. In her remarks, Burton emphasizes the unsettled and unsettling character of domesticity and challenges facile definitions of its global history. Fruitfully, she refuses to approach the six accompanying essays in their fixed order (nor have they been described that way here), instead prompting ways of reading the essays in pairs, backward and forward in time, and together as a kind of prospective course syllabus.

“History Unclassified” has become such a successful feature of the AHR that Bernas’s essay on Fukushima is one of two in this section in the October issue. It is accompanied by Charles Francis’s account of queer “archive activism” in his essay “Freedom Summer ‘Homos’: An Archive Story.” Francis, president of the Mattachine Society of Washington DC, describes the organization’s successful effort to document how the infamous Mississippi State Sovereignty Commission harnessed homophobia to crush gay civil rights activists during Freedom Summer 1964. Bringing together oral histories of openly gay African American activists and straight Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee organizers, informant reports, and the papers of segregationist Mississippi Governor Paul Johnson Jr., the essay shows how the Sovereignty Commission outed the students and faculty of historically black Rust College as “homos” and “queer” in an effort to smear President Ernest Andrew Smith, a supporter of Freedom Summer.

As always, research articles, roundtables, and “unclassified” essays are accompanied by a robust reviews section. In addition to the regular book reviews, the October AHR includes 10 featured reviews, including a close look by civil rights historian John Dittmer (DePauw Univ.) at a pair of recent books on civil rights photography in Mississippi. In a new determination to attend to matters of pedagogy as well as scholarship, the issue also offers a cluster of reviews of titles in the Bedford Series in Culture and History, document collections designed for classroom use.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.