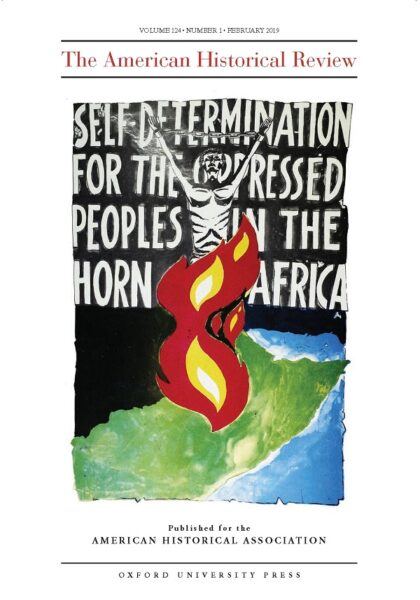

“Self-Determination for the Oppressed Peoples in the Horn of Africa.” Poster, Mogadishu, artist and date unknown. The Digital Somali Library, Indiana University. Visual, textual, and aural materials, including posters, pamphlets, and songs, circulated widely during the “long moment” of decolonization in Africa in the 1960s and 1970s. Often anonymously authored and shared through vast networks across colonial borders, these representations made claims to new forms of sovereignty through the reclamation of the visual language of the map and the redeployment of political rhetoric. The Kenya–Somali frontier erupted into violent conflict in the mid-20th century at the time of decolonization. Somali political activists used such posters to implore viewers to reimagine the border as a space of belonging. As Julie MacArthur demonstrates in “Decolonizing Sovereignty: States of Exception along the Kenya–Somali Frontier,” foregrounding the conceptual and rhetorical strategies of those living in borderlands challenges the uncritical dichotomy between territorial fixity and mobility, historicizes the discursive and practical content of sovereignty, and contributes to larger debates over the continuing global processes of decolonization. The conflict over the Kenya–Somali frontier reveals such borderlands as neither marginal nor exceptional, but rather as the core of postcolonial enactments of sovereignty.

The February 2019 issue of the American Historical Review features a Forum titled “Indigenous Agency and Colonial Law,” which focuses on the Americas. As Josh Reid (Univ. of Washington) observes in his introduction to the pair of essays in the Forum, rather than existing as mere victims of colonial expansion, “Indigenous peoples have engaged in the law to advance their priorities and to maintain or restore some control over their lives.”

The first article in the Forum focuses on a legal case from 17th-century southern Mexico. In “A Court of Sticks and Branches: Indian Jurisdiction in Colonial Mexico and Beyond,” Bianca Premo (Florida International Univ.) and Yanna Yannakakis (Emory Univ.) examine the 1683 arrest and trial of a native man at a makeshift rural court. Close attention to this case, they contend, offers glimpses of how imperial law on the books animated local understandings of jurisdiction on the ground. The case, by translating local events and native practices for a Spanish judge, demonstrates how “Indian jurisdiction,” a unique source of native authority within the Spanish empire, could be produced through engagement with imperial legal practices.

Examining a very different time, place, and legal environment, Miranda Johnson (Univ. of Sydney) analyzes the 1962 case of a Yellowknife Dene duck hunter who insisted on his treaty right to hunt as he pleased in a northwestern Canadian borderlands region. In “The Case of the Million-Dollar Duck: A Hunter, His Treaty, and the Bending of the Settler Contract,” Johnson recovers Canada’s indigenous peoples’ strategies for making sovereignty claims prior to 1970s native activism. Such claims undermined settler states’ legal frameworks with what Johnson calls “treaty talk”: the vernacular stories, civic rituals, and political disputes concerning the promises Canadian authorities made to northern indigenous communities earlier in the 20th century. Treaty talk, she claims, could pose a significant challenge to settler law and led one judge to reinvent a Canadian myth of benevolent empire. As Reid says, both articles in the Forum should be understood as “part of the larger historiographical context of what was once identified as ‘new Indian history.’” Their appearance together conjoins the indigenous history of 20th-century North America and 17th-century Spanish America in an unusual and fruitful way.

Fortuitously, the AHA Presidential Address (always published in the February issue) affirms the methodology embodied in these two articles. In her address, Mary Beth Norton (Cornell Univ.) reexamines her own historical practice to shed light on how looking at old evidence in new ways can generate novel questions. Drawing on the poetry of Emily Dickinson, she calls this writing “history on the diagonal,” and promotes the historiographical innovations of women’s, gender, and African American history, particularly in revolutionary and antebellum America, as a model for breaking open fresh approaches to understanding the past. Norton offers a number of strategies for engaging this method, including “taking a body of evidence collected in the past for one purpose and commonly used to investigate that same purpose, but instead employing it creatively for another” and “developing new analytical categories that supersede and replace older ones.”

Two other articles round out the issue. “From Cross-Cultural Credit to Colonial Debt: British Expansion in Madras and Canton, 1750–1800,” by Jessica Hanser (Yale-NUS College), makes credit relationships on imperial margins central to understanding how empires expand. Hanser’s comparative analysis of simultaneous financial crises in Madras and Canton during the late 18th century shows how voluntary and (initially) mutually beneficial financial transactions could transmute into imperial domination, as initial generous credit became the vise of colonial debt. Her article demonstrates how a global network of British brokers and investors connecting Madras, Canton, and London used legal, diplomatic, and military means to enforce their contracts abroad. The article reveals the process by which shifting debt and credit relationships amplified imperial engagement and reconfigured global and local relationships of power at a crucial moment in the British Empire’s history in South Asia.

The final article in the February issue shifts attention to decolonization in 20th-century East Africa. In “Decolonizing Sovereignty: States of Exception along the Kenya–Somali Frontier,” Julie MacArthur (Univ. of Toronto) shows how the borderland between Kenya and Somalia acted as a flashpoint for broader debates over belonging, security, and territoriality. Somali partisans variously resisted, negotiated, and confounded frontier governance and became the alien “strangers” in colonial Kenya’s racial order. Supporters of a “Greater Somalia” reconfigured diverse practices of mobility and kinship into an anticolonial rhetoric of trans-territorial statehood, even while Kenyan nationalists secured their own postcolonial vision by transforming Kenya’s northern frontier into a stage for violent performances of state power. As MacArthur argues, the emerging conflict over Kenya’s northern frontier in the 1960s was not merely a battle over territory or material resources, but over the very meaning of sovereignty, citizenship, and nationalism in a postcolonial order.

In addition to these six full-length articles, the February issue includes another contribution to our ongoing “Reappraisals” series, which examines classic historical works. The prize-winning historian of abolitionism Manisha Sinha (Univ. of Connecticut) revisits one of the signal works in that field, David Brion Davis’s The Problem of Slavery in the Age of Revolution, 1770–1823 (1975), in light of the recent scholarship on the history of slavery and capitalism. Her essay, “The Problem of Abolition in the Age of Capitalism,” places Davis’s book in the context of his intellectual biography, the well-known trilogy The Problem of Slavery, and his larger corpus of work on slavery and antislavery. In particular, Sinha focuses on Davis’s central argument about the relationship between abolition and the rise of capitalism, and the heated debates about capitalist hegemony, slave emancipation, and wage labor that his thesis continues to engender. It concludes by pointing to new directions in the history of abolition and exploring the impact of Davis’s scholarship on his students, innovative historians of abolition in their own right.

Finally, as is our habit these days, we include five reviews of recent documentary films: an essay by Mark Philip Bradley (Univ. of Chicago) on the Ken Burns and Lynn Novick television documentary The Vietnam War, as well as appraisals of recent films about race and eugenics, Historically Black Colleges and Universities, the Chinese Exclusion Act, and Lorraine Hansberry. The authors of these reviews—Molly Ladd-Taylor (York Univ.), Crystal A. deGregory (Kentucky State Univ.), Erin Chapman (George Washington Univ.), and Beth Lew-Williams (Princeton Univ.)—offer deeply informed perspectives on the presentation of the past in this form.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.