Editor’s Note: This is the first installment in a two-part column. The second column is available here.

“I’ve been thinking about pleasure, serenity, and joy lately,” J says, waiting as R and I fill a wheelbarrow with mulch. J continues working out the distinctions between the ideas, and when we finish shoveling, he takes the wheelbarrow and dumps it near a wildflower patch. Volunteers stand ready to spread mulch pathways through a pollinator garden, donated and planted by the local Sierra Club.

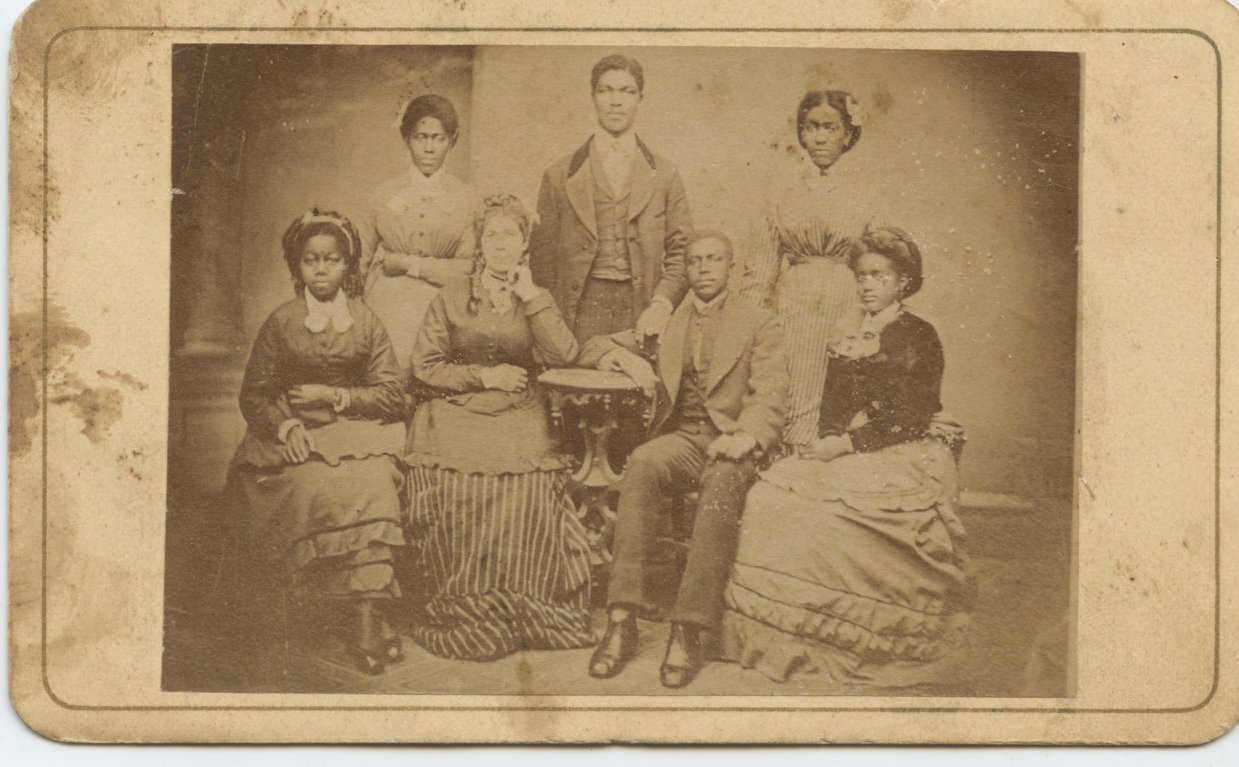

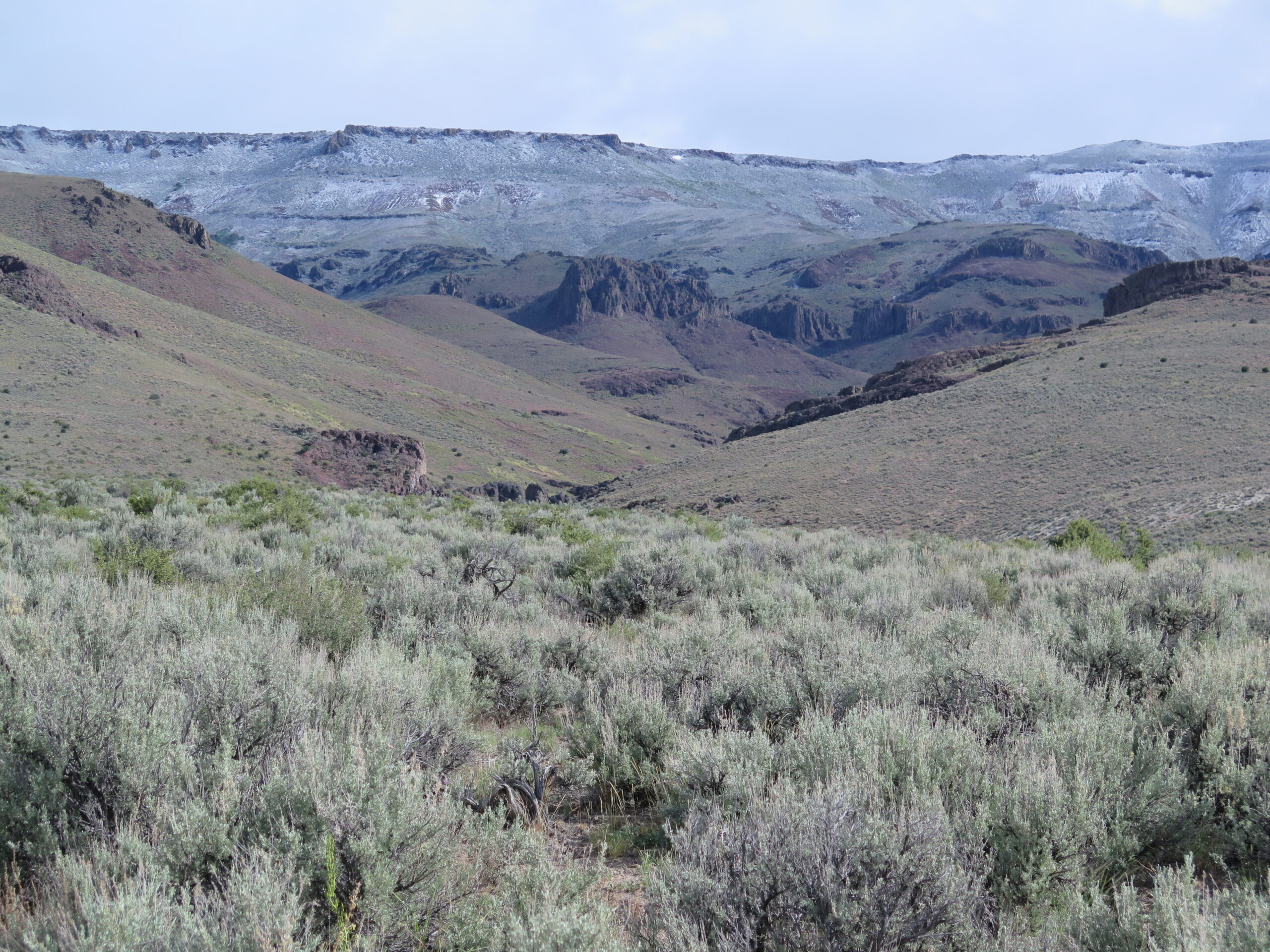

In her local community garden, Cecilia Slane has shared her historical expertise. Cecilia Slane

It’s 9:00 a.m. on a Saturday. A dusting of cotton from a nearby cottonwood tree covers the park in Norman where our community garden lies. It looks like snow in an Oklahoma June. As we shovel mulch, we have thoughtful conversations about identity, community, technology, environment, science, and even historical method (partially, but not entirely, my contribution). I find myself stretching the same mental muscles that I do in my graduate seminars but with neighbors who are dancers, social workers, grocery store stockers, university workers, and homemakers. I always feel a spark of excitement when I can contribute historical context to the conversation; luckily, my research topics—science, technology, environment, and energy—feature in many of our conversations about growing food for the local community. In these conversations and the garden’s activities, the garden becomes a space for legitimate historical practice, communication, and connection to Oklahomans of the past.

Cecilia Slane

Our primary goal is to create a welcoming community space that provides food and resources for nearby neighbors. Volunteers and neighbors get first pick of the cucumbers, tomatoes, beans, peppers, greens, and other produce that we grow, and then the remaining harvest is donated to a nearby free food pantry. There are no fences or fees here, no barriers to entry or harvest. This year, the garden committee (a group of four volunteers who coordinate garden planning, labor, and activities) decided to prioritize the garden as an educational space, where we can share knowledge about plants, cooking, and local goings-on in the community. Many of the volunteers are historically minded, thinking with and asking questions of what community gardens are for and what role they have played in tumultuous times. Alongside plants and green space, we cultivate various knowledges in ways both unstructured and structured.

First and foremost, the garden is a place to learn about nature. You can see pollinators visiting our native flowers and learn from other neighbors about what plants do or do not grow well in Oklahoma. One morning, a neighbor showed us how to cut out the squash bugs that had taken over our pumpkin patch. These are all intellectual exercises that we find valuable, but I also find this knowledge-sharing exercise to be a way of doing history. We share gardening advice shared with us by elders (some of whom we’ve never met) and knowledge gained during historical periods like the Dust Bowl, a significant memory for Oklahomans to this day. Through simple conversations about bug control and soil erosion—and the physical tasks needed to address them—we carry on historical memory as a community.

Many of the volunteers are historically minded, thinking with and asking questions of what community gardens are for and what role they have played in tumultuous times.

Yet we have gone further into historical education, notably through events and a zine project. Our host organization, Red Dirt Collective (RDC), holds a monthly Community Conversation at a church across the street from the garden. RDC members organize a potluck (or order pizza, if folks have been busy), choose a discussion topic or activity, and spend the evening chatting about the neighborhood as well as local and national concerns. Community Conversation has hosted Stop the Bleed trainings, crafting nights, and, during an evening hosted by garden volunteers, a dinner and discussion about the history of community gardens and agriculture in Oklahoma and the broader United States.

For this event, the garden committee prepared a veggie soup dinner (with some ingredients from our garden) and a 30-minute lecture covering topics such as World War II–era Victory Gardens, school gardening programs, and Oklahoma’s 1917 Green Corn Rebellion. We wrote lecture notes in a Google Doc and edited a shared Canva presentation. We printed a bibliography, which provided a combination of accessible online sources from websites like the Smithsonian’s, alongside peer-reviewed sources (with an explanation of how to request through interlibrary loan books and articles unavailable at the public library). We spent two weeks preparing the lecture materials, collecting photos, and organizing our narratives; the result was a cozy evening of roughly 20 people eating dinner and talking together about the history of gardening.

Cecilia Slane

This structured event resembled a classroom setting, using many of the skills that we instructors already have. However, we use a different method of doing history in our zine project, Cultivating Commons. We’ve created three zines so far, each reflecting the season of publication and ideas that garden volunteers have been collaboratively thinking with. I found that the zine presents an opportunity for interplay of history and historical thinking with multimedia art for a broad audience. In December 2024, the first zine focused on the second word of the title, with an essay touching on the history of enclosure of the commons in England and the allotment process in Oklahoma. One contributor wrote about the Dawes Act of 1887, which dispossessed Native Americans of their lands in Oklahoma and made “unassigned” plots available to purchase for white settlers, an act of settler colonial force in so-called Indian Territory. The writer connected these events directly to our garden, which sits in a park called Colonial Commons, in a town created by the 1889 Land Run. Oklahoma’s past is full of examples of settler colonial dispossession, though that is not always reflected in the teaching of the state’s history. Since moving to Norman in 2021, I’ve learned from many Oklahomans that they learned about the Land Run through historical reenactment of settlement, with little care or attention for the people whose lands were taken. Our most recent zine, “Practicing Queer Ecologies,” reflected on the historical importance of gardens as safe spaces for queer folks and as spaces of resistance to food insecurity, environmental injustice, and dispossession. Through these zines, we show that history is not just the big moments of elections, battles, and birth and death dates. History is also in the name of your local park, in the gardening skills of your neighbor, and in the recipes you share for community dinner.

The first zine included an essay touching on the history of enclosure of the commons in England and the allotment process in Oklahoma.

Here is the garden, a space for building community, historical education, and memory. The history that we do is not driven by a formal research plan but by the interests of the neighborhood. Rather than thinking, “How do we get historical information about gardens to the public?” we asked, “What do we want to know?” Among the historians at the garden, our approach has been to recognize that we are in the public, not a separate entity. I talk about history at the garden in the same way that I talk to friends, family, neighbors, and the workers who make my life possible. I’ve found that most people seem interested in what exactly it is that I do and what I know.

I think “reaching the public” is made more difficult when we create an invisible barrier between “us” (historians) and “them” (the public). Community members, those in and out of the university, have contributed valuable historical ideas, art, and writing to the zines and community discussions. At the garden, we’re driven by growing food and collaborative community building, not citation metrics or promotion files. In thinking about how to make complex, nuanced, and critical histories meaningful in a moment when historical education and knowledge is devalued and assailed, it will take creative endeavors and new avenues of social interaction. It will require getting out of our comfort zones, out of the classroom, and into third spaces that the “public” inhabits. Along your way, have conversations about history, what it means, why it means something to you, and how to do it. Go get your hands dirty!

Cecilia Slane is a PhD candidate in the history of science, technology, and medicine at the University of Oklahoma, where she studies fossil fuels in the history of science, technology, and settler colonialism.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.