“Patient has an anxious frightened and distressed expression . . . is unhappy and emotional . . . .” During the First World War, such descriptions were often used in case notes to describe patients with shell-shock. This particular description comes from the case notes of a woman named Margaret Müller, a Belgian refugee who was admitted to Colney Hatch Asylum in 1915. I found Müller’s case notes during my dissertation research, thanks to the help of the dedicated archivists at the London Metropolitan Archives. Müller’s story sheds light on the sometimes overwhelming effects of war on noncombatants, as well as the treatment that many women received in hospitals on the home front.

Before the establishment of the National Health Service in 1948, those unable to afford private treatment in Britain received care through charitable institutions such as hospitals and dispensaries, local officials, or under the Poor Law. Over 80 of these hospitals—many of which have now closed—deposited their extant records at the London Metropolitan Archives. These records range in scope and in condition, but where case notes are available, they provide fascinating, and often moving, insight into the history of medicine, gender, and the First World War.

The case notes are significant not necessarily because (or not only because) of the medical diagnosis of the patient, but because they reveal a power relationship between the patient and her doctor, a relationship that is colored by medical and cultural assumptions about gender and emotionality. This is especially true in the case of Margaret Müller. Though access to the specific records in which I found Madame Müller’s case notes is prohibited under British Data Protection legislation, I obtained special permission from the London Metropolitan Archives to consult them.

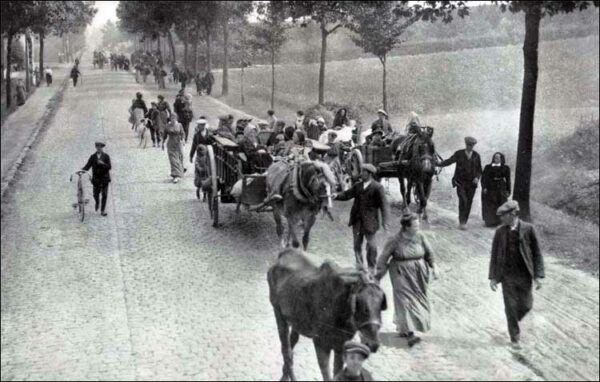

With its 1,250 beds, Colney Hatch Lunatic Asylum, located in what is now the London Borough of Barnet, was the largest asylum in Europe when it opened in 1851. By the turn of the century, the asylum had grown to house over 2,500 inmates. Superintendent’s Report Books from several public hospitals paint a picture of institutions such as Colney Hatch as incredibly stressful places for patients and staff alike during the war. Men were leaving hospitals to enlist in such numbers that, often, hospitals were too understaffed to operate according to regulations. Doctors were responsible for dozens, if not hundreds of patients—a situation that was only exacerbated by wartime deprivations, safety concerns, the initiation of air raids on London, and the influx of Belgian refugees, many of whom were housed in these hospitals when beds could not be found for them elsewhere. Hospitals were loud and confusing places where patients were crowded together, and often restrained due to understaffing.

It was into this environment that Margaret Müller entered in October 1915 at the age of 52. From the standard information taken upon intake, we can learn that she was a Belgian refugee, without family, who had been suffering from “Prolonged Stress” for nine months. The intake also notes that she was “poorly nourished,” but otherwise in fair health. The photo taken upon her admission shows a woman who appears older than her age—her dark hair has streaks of gray framing her face; she has heavy shadows under her eyes, but seems to be offering a small smile to the camera.

None of Müller’s words are recorded in her case notes. Instead we learn from an interpreter and from her attending doctor, Reid, that she was constantly fearful of being mistaken for a German. According to Dr. Reid, “She appears to suffer from Auditory hallucinations—voices through telephone speak to her. She has a delusion that people mistake her for a German, and want to do her an injury as a result.” He further noted, “She is suffering from Melancholia. She is depressed, lacking in emotional control and exhibiting much apprehensiveness.”

Margaret’s condition at the hospital, and her relationship with the hospital staff, did not improve after she was admitted. At the end of October, hospital staff noted that there was “No change, still very agitated and worried. She asks for work but when it is given to her she fails.” One week later, they recorded that she “worries the staff a good deal for employment, which when given she cannot settle herself to do.” By December, she was so “restless and agitated” that she was confined to bed for three days, in the hopes that “greater quietude” would ease her symptoms. Instead, she was “much worried by hearing voices declaring ‘She is a German.’” There was no change to her case until December 27, when it was discovered that Margaret Müller had hanged herself using her apron strings.

There are many things historians can learn from these case notes about Margaret Müller, and about the way her symptoms were received and treated by the staff at Colney Hatch. Her case sheds light onto the experiences of Belgian refuges in Britain during the First World War, and her desperate need to establish her identity in a world that was unknown to her and in which she was totally unknown. It also provides a great deal of information on the gendered nature of psychological treatment during this period.

Historians such as Joanna Bourke and Fiona Reid have discussed how shell-shocked soldiers underwent a treatment of “re-masculinization”: teaching them to don a uniform, take up arms, and defend their country. The process of treatment for women was often a similar process of “re-feminization” that relied on teaching them to be dutiful, productive, and cheerful. Margaret’s “lack of emotional control” reflects the belief in psychology at the point that men had emotions, but women were emotional. Margaret’s case notes make it clear that the asylum’s goal was to reeducate her to be less emotional, quiet, and docile, and that her failure to complete tasks, or to control her expressions of fear and anxiety represented a failure to behave according to proscribed gender norms.

There are some things that remain unknowable, however. There is no mention about what happened to Margaret before her arrival at the hospital, or if a specific incident caused her to fear being mistaken for a German. This is no doubt in part due to her inability to communicate her experiences in English (as the references to an interpreter in the case notes indicates). Individual memory, however, did not play a major role in the discourse of trauma at the time, war-related or otherwise. Freudian analysis was known, but it was eschewed by most British doctors and psychologists. Though changes would be made eventually as a result of the study and treatment of war-related trauma, those changes were mostly for the benefit of soldiers and male veterans. For civilians, and especially for refugees like Margaret Müller, 19th-century beliefs about gender, emotionality, and predisposition guided psychologists’ treatments.

Margaret’s case notes exemplify a particularly grim example of the effect that trauma, and a lack of understanding of trauma, could have on an individual. Perhaps because of this, I find her story, and her portrait, unforgettable. Margaret remains a constant reminder to me of the very real, human experiences that form the basis of trauma studies, and the need to include such stories in history of war trauma.

This post first appeared on AHA Today.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.