Few would turn down an opportunity to visit Los Angeles in late February. But when over 100 historians, including graduate students, faculty, and colleagues employed beyond academia, descended upon the University of California, Los Angeles, campus on February 25, sunshine and warm temperatures were not the main attractions. Instead, the group had convened for “Futures of History: Discussions, Demonstrations, Displays,” a two-day conference hosted by the UCLA Department of History, home to one of four pilot programs for the AHA Career Diversity for Historians initiative. Organized by Graduate Career Officer Karen Wilson and graduate students Grace Ballor, Kristina Markman, Kelly McCormick, and Kate Creasey, the conference aimed to empower the next generation of historians and defend the value of historical training by facilitating conversations about graduate education in history, the work of historians, and how we might redefine both in order to meet the challenges and opportunities facing the discipline today.

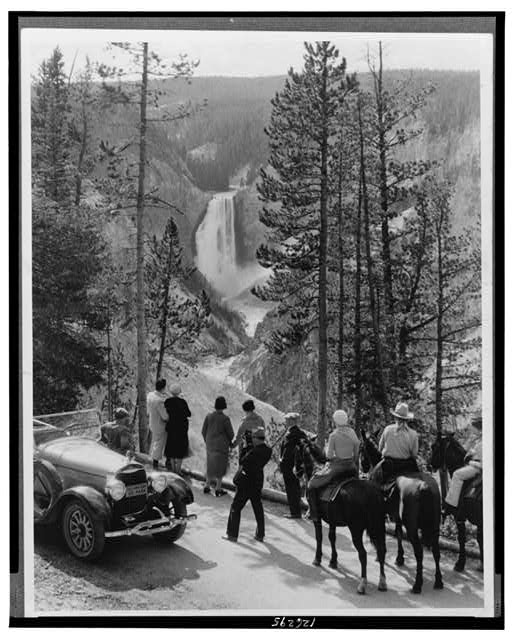

California sunshine and the UCLA campus. Credit: Lindsey Martin

The conversations that emerged during two days of panels and breakout sessions were united by a few common themes related to graduate training in history and its professional outcomes. One was the need to reconceptualize what it means to work as a historian, which for many is synonymous with an academic appointment. Panelists employed outside the professoriate, however, argued that historians should be defined not by where they work, but how. As Kim Gilmore, senior historian and vice president for corporate outreach for HISTORY and A+E Networks, contended, our discipline is distinguished by a historical sensibility that shapes the way we ask questions and solve problems, and which does not suddenly evaporate if one leaves the tenure track. Gilmore noted that the boundaries between academic and nonacademic work are far more porous than usually assumed. For her, the decision to pursue a career beyond the academy was not a sharp break with her dissertation research, but a continuation of pursuing the same intellectual questions that had motivated the project.

Lance Blyth, historian for NORAD and USNORTHCOM, speaking in his personal role as a practicing historian, indicated another recurring theme: if we accept that there are many ways of being a historian, then it is not sufficient for graduate programs to tacitly acknowledge the wide range of career paths for doctorates in history. Instead, programs must actively embrace alumni employed in diverse fields and encourage them to serve as mentors and models for current students. As Blyth noted, this could be accomplished quite easily by inviting alumni working beyond academia back to campus to speak about their research. Such a simple step, he argued, would speak volumes about a department’s commitment to training future historians and celebrating their many career paths.

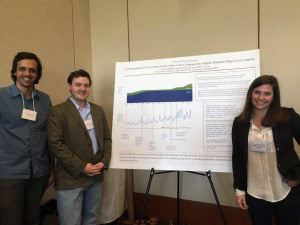

Anthony Vivian, Preston McBride, and Jennifer Tiari present their project, “Understanding the UCLA Labor Center’s Role in the Campaign for a Higher Minimum Wage in Los Angeles,” during the HistoryWorks poster session at the Futures of History conference. Credit: Sona Tajiryan

A curious strain of the conference was how efforts to grapple with big issues confronting the discipline frequently provoked debates about the very words and terminology used to discuss graduate education and the work of historians. To some extent, conference organizers invited this line of questioning when they titled the conference “Futures of History.” As Karen Wilson explained via e-mail, the group deliberately chose the plural “futures” with no definite article to recognize that members of the discipline “are not all headed for the same future or even a couple of the same futures.” Furthermore, they were seeking to disrupt the dichotomy that the only career choice for graduate students is to become a professor.

Others readily followed their lead. Both Jim Grossman, executive director of the American Historical Association, and Steve Aron, chair of the UCLA Department of History and faculty director of its AHA Career Diversity pilot program, pushed back against the term “production” to describe PhDs, reminding the group that a doctorate is not something produced by programs, but earned through much hard work by graduate students. Similarly, participants debated the language used to describe employment opportunities for historians. Grossman, for example, rejected the notion of career “placement” for PhDs, and others considered the utility of describing a singular “job market” for historians versus multiple “job markets” separated into academic and nonacademic career paths.

Annie Maxfield, associate director of graduate student relations and services at the UCLA Career Center, asked graduate students at the Futures of History conference to ponder some deep questions about their professional goals and values as she guided them through a career exploration exercise. Credit:

On one hand, scrutinizing the language we use to discuss the discipline and its job prospects may seem entirely beside the point; after all, simply changing whether or not we describe the job market as a singular or plural phenomenon will neither halt the steady decline of tenure-track positions nor alleviate the pressure placed on graduate students to single-mindedly pursue those jobs at the expense of others. But on the other hand, questions like these are at the heart of the AHA’s efforts to explore the culture and practice of graduate education through its Career Diversity initiative. As historians, we are highly attuned to the power and meaning of language. Grossman, for example, provocatively pointed out that referring to faculty course requirements as a teaching “load” betrays an assumption in the discipline about teaching as a distraction from the “real” work of professors (i.e. research and writing), rather than a fundamental part of what it means to be a historian.

Discomfort with language stemmed from a final theme of the conference: the need to empower graduate students to chart their own courses as historians. Terms such as “production” and “placement” of PhDs withhold agency from students; rather than describing them as individuals earning degrees and pursuing careers, both imply that the purpose of historical training is to simply reproduce existing academic models. Instead, Elaine Carey, associate professor of history at St. John’s University, argued that graduate programs and the language we use to describe them must have a space for students to ask, “What makes you tick?” Allowing young historians to explore their intellectual passions, even if that takes them beyond the tenure track, is not simply empowering for graduate students. Any career path that demonstrates the value of history and advocates for the relevance of historical training is ultimately a boon to the discipline, and one that makes its future—or rather, futures—a little brighter.

This post first appeared on AHA Today.

Lindsey Martin is the coordinator of Making History Work, the AHA Career Diversity initiative at the University of Chicago. She received a PhD in Russian history from Stanford University in 2015.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.