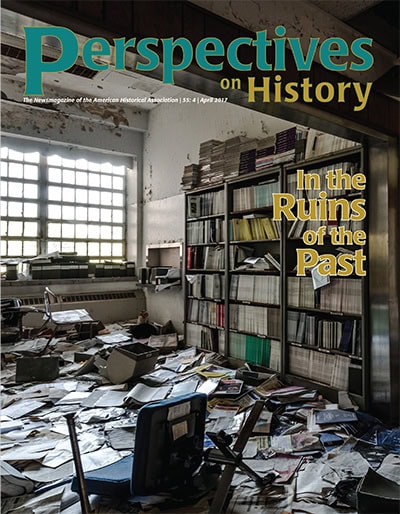

With Eliot’s “cruelest month” upon us, Perspectives considers the role ruins and the destruction of cultural heritage play in history. The subject might evoke the Taliban’s demolition of the Buddhas of Bamiyan in 2001 or, more recently, the terrorist group Daesh (ISIS), its role in the illegal antiquities trade, and its devastation of heritage sites in Palmyra. But as Rachel Van Bokkem shows in “History in Ruins,” the destruction of cultural heritage is far from a new phenomenon, nor is it limited to one part of the world or a few groups of people. Byzantine historians have worked for years to tell the story of seventh- and eighth-century Iconoclasm. Without malicious intent, simple human neglect can destroy sources, but the problem also lurks when urban developers are capricious about cultural heritage. The impact of destruction is more complex than it appears.

The AHA’s own Elizabeth Elliott looks at ruins closer to home, in “Picturing Jewish Vacationland,” which takes us to New York state’s Catskill Mountains—the old Borscht Belt. For the uninitiated, the Catskills hosted a welter of summer resorts, largely patronized by middle-class Jewish Americans (think Dirty Dancing). Now, however, the Borscht Belt is deserted and decrepit, its swimming pools drained, its once-splendid amenities covered in dust. Photographer Marisa Scheinfeld visited the ruins of the Catskills to produce The Borscht Belt, a book of images that are each carefully contextualized. The result, says Elliott, is a window into American Jewish history and culture.

The AHA’s own Elizabeth Elliott looks at ruins closer to home, in “Picturing Jewish Vacationland,” which takes us to New York state’s Catskill Mountains—the old Borscht Belt. For the uninitiated, the Catskills hosted a welter of summer resorts, largely patronized by middle-class Jewish Americans (think Dirty Dancing). Now, however, the Borscht Belt is deserted and decrepit, its swimming pools drained, its once-splendid amenities covered in dust. Photographer Marisa Scheinfeld visited the ruins of the Catskills to produce The Borscht Belt, a book of images that are each carefully contextualized. The result, says Elliott, is a window into American Jewish history and culture.

Moving from the past into the future, Paul Sturtevant’s “History Is Not a Useless Major” is more than preaching to the choir. Most of us have heard some version of the “uselessness” refrain and perhaps struggled to respond. Sturtevant dives deep into data from the American Community Survey (ACS), a fine-grained study conducted by the US Census Bureau, to put to rest this myth once and for all. People with bachelor’s degrees in history go into a variety of careers. It’s true that some are more remunerative than others, but it’s patently false that a history degree is a sure path to unemployment or even underemployment. This conclusion and others, all based on concrete data, make the piece worthy of sharing with undergraduates, parents, professors, and department chairs.

But as Brandon Locke points out in this month’s Viewpoints column, “Protect Government Data for Future Historians,” data like the ACS need to be preserved actively. As our country faces proposed budget cuts in agencies that collect data for the public—including data on climate change and racial patterns in housing—historians must understand that they have an interest in preserving this data, both for the public and for members of the historical community yet to come. Locke has been instrumental in founding Endangered Data Week, a series of events designed to get scholars involved in hands-on preservation. Find out how you can help.

In the second in a two-part series featuring the winners of the AHA’s Equity Award, the chair of the Committee on Minority Historians, Melissa Stuckey, puts questions about access, policy, curriculum, and the PhD pipeline to our 2016 institutional Equity Award winner, the University of Texas at El Paso. Over the years, UTEP has successfully graduated a number of students of color and from less-privileged backgrounds who have gone on to receive doctorates. The department shares concrete strategies anyone can take to promote equity in the near and far term.

Our AHA leadership columns continue their forward-thinking ways. AHA president Tyler Stovall considers the ways historians use anniversaries as springboards into research and writing. The anniversaries in 2017 include the Russian Revolution, the US entry into World War I, and the Summer of Love. AHA executive director James Grossman gives space to the reasoning that goes into the Association’s decisions to speak out on policy matters germane to history and historians.

Finally, Sadie Bergen examines some of the practices and innovations of scholarly collaborative blogs, staffed mostly by early career historians and graduate students. As many in the discipline consider presenting their work to multiple publics (scholarly and popular), blogs play a significant role. They also allow bloggers to think seriously about professionalization and how their work will be assessed in the future.

Finally, this month’s “Townhouse Notes” expands my thinking on collaboration, which I discussed in the March issue of Perspectives. This month, I consider friendship—what it means to scholars and what it means to our work.

There’s more to dive into. Enjoy.

This post first appeared on AHA Today.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.