Asked to describe how they learned to teach with primary sources, one instructor recalled, “I was like a deer in headlights, had no idea what I was doing, so I had to figure it out.” This sentiment, reported in Ithaka S+R’s recent Teaching with Primary Sources project, resonated with my experience designing and teaching an introductory history course. I had minimal instruction and even less supervision while building my first courses as a doctoral student.

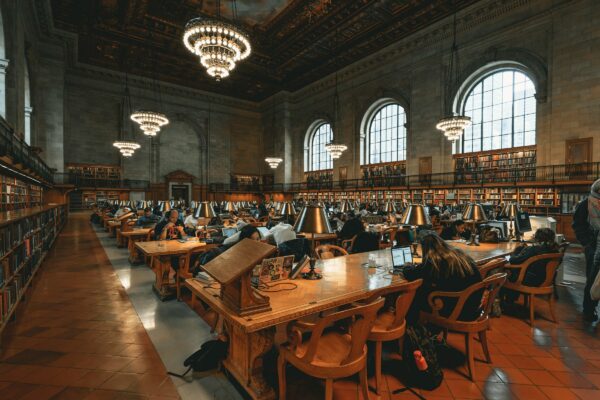

A new report from Ithaka S+R found that history instructors need to collaborate with librarians, archivists, and publishers to help students master the skills required to find and use primary sources. Clay Banks/Unsplash

Few disciplines rely more heavily on primary sources as instructional tools than history, but many of us find that learning to teach effectively with them is difficult. Faculty can turn to a sizable and valuable literature exploring the pedagogy of teaching with primary sources, much of it focused on case studies of single courses or assignments. But part of teaching students to engage with primary sources depends on teaching them how to navigate libraries and archives and use resources like card catalogs, finding aids, and search engines. These skills are difficult to master across a major, let alone within a single course. As historians, we want our students to experience something of the joy we discover in the open exploration of primary sources. But what does it take to get them there?

In Teaching with Primary Sources, Ithaka S+R sought a broad perspective on how universities—particularly, university libraries—can support faculty who teach with primary sources. Working in partnership with ProQuest and 26 institutions, including liberal arts colleges, regional public and private universities, and research universities, the Teaching with Primary Sources project (not to be confused with the Library of Congress project of the same name) generated interviews with 335 faculty (roughly one-third of them historians) who detailed how they and their students discover, access, and use both physical and digital primary sources in upper- and lower-division courses. The resulting report highlights common challenges that instructors face regardless of academic field and offers examples of successful collaborative instructional practices between faculty and librarians. One of the project’s core findings is that primary source pedagogy benefits from collaboration between teachers, departments, librarians, and publishers, each of whom plays an important role in helping students gain experience discovering and interpreting primary sources.

Few disciplines rely more heavily on primary sources as instructional tools than history.

Despite almost unanimously reporting that they began their career as a “deer in the headlights,” most faculty said that they were now fairly comfortable teaching students to interpret primary sources. Typically, this involved assigning students carefully curated materials from readers, open-access or subscription digital collections, and sometimes physical objects held by university archives or special collections. Many instructors used primary sources to provide students with opportunities to understand how historical arguments are made. As one instructor noted, “It’s really [about] teaching students key historical skills to be able to assess evidence and develop arguments based on competing evidence.” To facilitate this learning, instructors invest considerable time creating packages of complementary sources that students used to stage debates.

However successful these practices were at teaching students to engage with primary sources, they fell short when it came to teaching students to find their own primary sources for analysis. This important skill—the ability to locate and sift through “raw” sources and make independent judgments about their value, perspective, and relevance—is at the core of historical research and information literacy. Instructors who had tried to integrate primary source discovery into their courses noted that students struggled to evaluate the quality and relevance of what they found, becoming discouraged or gravitating towards resources that popped up readily through Google searches. Faculty voicing these concerns were not accusing their students of laziness: they recognized that students were juggling many personal and intellectual demands on their time. Nevertheless, there was a palpable sense of frustration among instructors at their lack of success teaching students to conduct open-ended research and find their own primary sources. Faced with these challenges, many faculty, especially those teaching in lower-level courses, settled for providing sources rather than requiring or encouraging students to discover their own.

Evidence emerged of a common curricular gap: instructors felt that teaching research skills was too advanced for their lower-division courses, but also felt that it was something that students in upper-division courses ought to already know. Everyone recognized the importance of students, especially majors, learning these skills along the way, but exactly when they should be taught—and by whom—remained elusive.

Working with primary sources requires significant intellectual dexterity.

Individual faculty cannot bridge this gap alone. They will need to collaborate with librarians, archivists, and publishers. Many of the faculty who were most successful in having students find their own sources had developed long-term collaborative relationships with librarians and archivists with expertise in helping students navigate databases and special collections. Publishers—including digital content providers such as EBSCO and ProQuest—have a role to play as well. They might consider building “sandbox” style collections of primary sources, with enough curation to structure student exploration but sufficient depth and diversity to allow for an authentic discovery experience. Digital collections hosted by major research institutions or museums might consider similar ways of highlighting resources of the right length, genre, and language to be broadly useful for students at various levels.

As historians know, working with primary sources requires significant intellectual dexterity: doing it well demands information literacy, command of search and discovery, and the domain knowledge necessary to contextualize what you find. Perhaps the most significant implication of the Teaching with Primary Sources project is that it takes more than a single course for students to master this mix of skills. If we want students to be ready to practice historical research at the level of a capstone project at the end of their university careers, we should be thinking about how to provide students with incremental opportunities to move from reading a small number of preselected primary sources to finding and evaluating sources on their own. As AHA initiatives like Tuning and History Gateways have shown, history education benefits from approaches that think about individual courses in relation to the curricula as a whole and that emphasize disciplinary competencies that are developed over the course of a degree program. The Teaching with Primary Sources project underscores the importance of this holistic approach and suggests an ongoing need for more conversations about how to scaffold primary source discovery across courses, within the curriculum, and as a core learning outcome for the major.

Dylan Ruediger is a qualitative analyst with Ithaka S+R’s Libraries, Scholarly Communication, and Museums program. He tweets @dylan_ruediger.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.