The first time I realized my love for history and the outdoors could be combined into a single career, I was sitting in a graduate class I was not even enrolled in. A cultural resources specialist from the National Park Service (NPS) gave a presentation about working in cultural resources management. As I listened, I realized for the first time that there were opportunities to combine history and the outdoors into a single job.

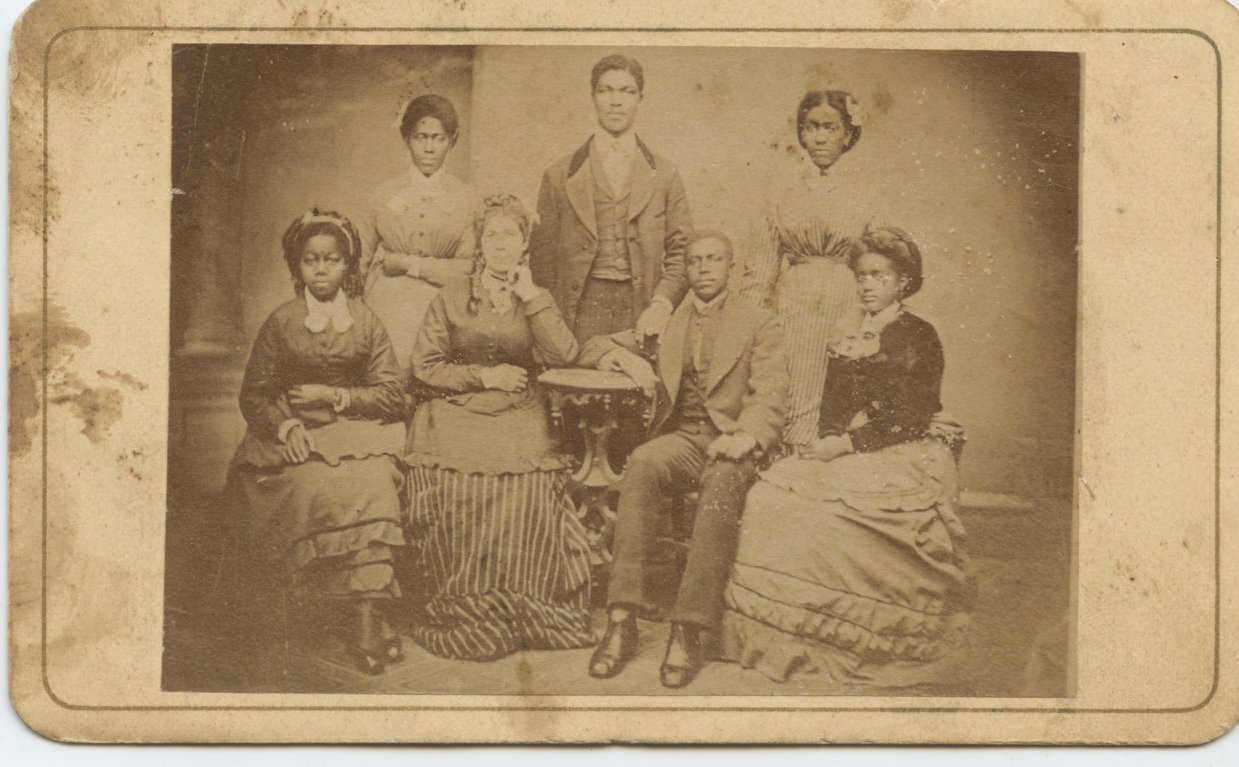

Allison Isham is working this summer for Whiskeytown National Recreation Area with the National Council of Preservation Education. Courtesy Allison Isham

That day is what ultimately convinced me to pursue a master’s degree in public history. My journey to public history consisted of a combination of career changes, supportive mentors, and figuring out what my true passions are. While my time in academia did help shape my decision, my experiences and interests outside academia showed me that a career in parks and cultural resources management is what I want to do.

My parents instilled in me at an early age the importance of being outdoors. I spent hours playing outside with friends, shooting basketballs, and drawing chalk cities. I played soccer for 13 years and softball for five, and I cherish the memories of spending time outside with my teammates both on and off the field.

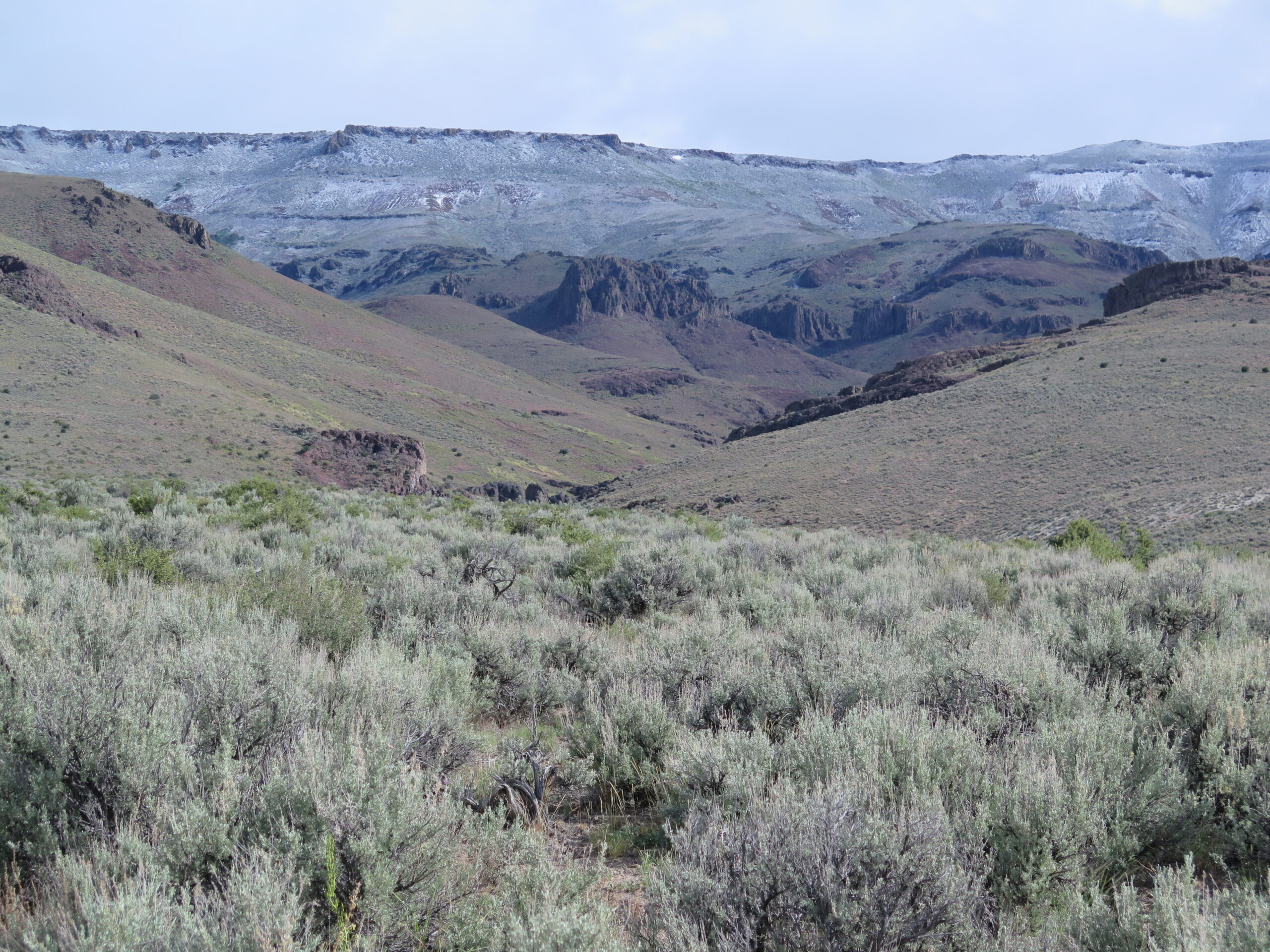

Family vacations reinforced my parents’ belief in the value of being outside. We frequently went camping near Lassen Volcanic National Park. Wherever we traveled, my dad made a point of taking us hiking. On these trips, I loved going to new places and learning about their local histories. No matter where we traveled, I enjoyed reading interpretive signage and visiting museums. It always amazed me how each place I visited had a rich, unique history, and I enjoyed delving deeper into understanding the people and events that shaped the present in the places I visited.

Each place I visited had a rich, unique history.

In addition to a love for the outdoors, my parents instilled in me the importance of hard work. My first job at age 12 was umpiring youth softball games, which began my 10-year stint working in parks and recreation. Over eight years, I climbed my way to head umpire. I trained dozens of new umpires, emphasizing work ethic, leadership, and de-escalation tactics. In my sophomore year of high school, I began working for my soccer club, painting soccer fields for nearly 30 different parks and schools. The next year, my local parks and recreation department hired me to run the snack bar at the city’s indoor sports complex. I worked there until the COVID-19 pandemic closed the complex for nearly a year.

I started college at Folsom Lake College as a history major, but I realized that I had loved my parks and recreation jobs because they allowed me to work outside and be an active part of influencing peoples’ recreational activities. I asked my old manager if I could work as a receptionist and manager of the indoor sports complex. Over the next five years, I climbed the ranks within the parks and recreation department and eventually worked as a facility supervisor and program manager. I oversaw the operation of nearly all our department’s sports programs and trained dozens of staff. When I transferred to California State University, Sacramento, I added a minor in recreation management, as I planned to pursue a career in parks and recreation after graduation.

But Patrick Ettinger, my advisor at CSU Sacramento, helped me to find ways to combine these two passions. In his courses, I completed assignments on environmental history, the history of preservation and conservation in the United States, and the American West. Dr. Ettinger guessed that my love for the outdoors and interest in national parks might be best fulfilled as a public historian. The fall semester of my senior year, he invited me to attend a session of the introductory graduate public history course, which was discussing a book I had read in his seminar and being visited by an NPS employee.

My mentor guessed that my love for the outdoors and interest in national parks might be best fulfilled as a public historian.

The cultural resources specialist described his work in cultural resources management and how he uses his master’s degree in public history. He writes reports on historic resources found in national parks and aids with historic research for potential new park sites. He travels to existing national park sites and conducts research on the nation’s history. Though at times his work can be extremely specific in scope, he explained that it always has the power to impact park planning and visitor experiences for generations. The public is often involved in his work through collaboration and outreach, which reminded me of things I had done in my municipal parks and recreation job. Previously, I had assumed that NPS careers were limited to park ranger positions, but this presentation unveiled to me a different side of the national parks. Everything he detailed appealed to me, especially the research topics and travel components. This presentation ultimately convinced me to apply for Sacramento State’s graduate program in public history.

What I learned during that presentation, and subsequently in my master’s program, is that careers in history can bring together our academic passions and experiences outside academia. My upbringing and decade working in parks and recreation directly shaped my decision to pursue a career in public history. With my advisor’s help, I have connected the dots between my love for recreation and the outdoors with my passion for history. What I thought were two completely unrelated passions have merged into viable career path in the field of cultural resources management, a career that will allow me to get outside, research places that matter to people, and positively shape peoples’ experiences for generations to come.

Allison Isham is a master’s student in public history at California State University, Sacramento.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.