The June issue of the American Historical Review features articles and forums that rethink approaches to global, environmental, and intellectual history and introduce readers to new methods in historical digital scholarship.

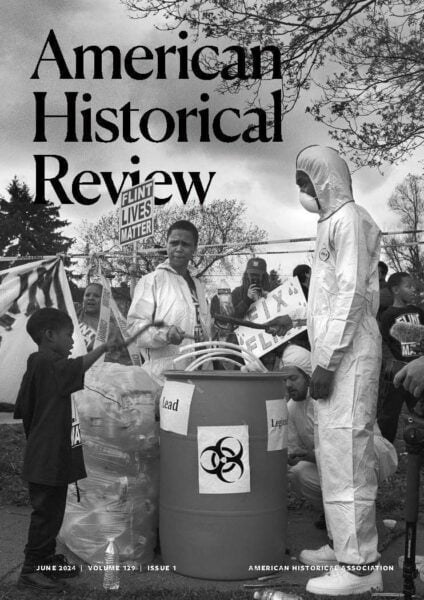

The June AHR includes a featured review of recent scholarship on the Flint water crisis and histories of environmental justice. The cover image is drawn from the visual artist, photographer, and MacArthur Fellow LaToya Ruby Frazier’s Flint Is Family in Three Acts project, for which she spent five years in Flint, Michigan, documenting the lives of those most affected by the city’s water crisis. In approaching her project, Frazier was inspired in part by a collaboration between photographer Gordon Parks and writer Ralph Ellison for their 1948 “Harlem Is Nowhere” essay that explored the psychological effects of racism on Black residents in Harlem. Through photographs and text, Frazier examined the disproportionate impact of the water crisis in Flint, where Black residents make up a majority of the city’s population and more than 30 percent of the population lives below the poverty line. LaToya Ruby Frazier, “Flint Students and Community Members outside Northwestern High School (Est. 1964) Awaiting the Arrival of President Barack Obama, May 4, 2016, Flint, Michigan, II,” 2016–17. Gelatin silver print. 24 × 20 inches (61 × 50.8 cm) © LaToya Ruby Frazier. Courtesy of the artist and Gladstone Gallery.

Elizabeth Chatterjee’s (Univ. of Chicago) “Late Acceleration: The Indian Emergency and the Early 1970s Energy Crisis” explores how the global energy crisis briefly unlocked a radically new horizon of possibilities that played out differently around the world. In India, she argues, the crisis did not begin with the famous Arab oil embargo of 1973. Instead, like many poor oil-importing nations, India experienced the first oil shock as merely one component of a broader climate-food-energy emergency that reverberated throughout the political system and brought a twinned set of fateful changes: the imposition by Prime Minister Indira Gandhi in June 1975 of a constitutional dictatorship called the Emergency, and a parallel state-led embrace of coal despite elite reservations about the environmental damage that would follow. Chatterjee argues that these genealogies also provide the origin story for today’s carbon-intensive energy regime in India and the accompanying challenges of climate change.

Sarah Thal’s (Univ. of Wisconsin–Madison) “Chivalry without Women: The Way of the Samurai and Swinton’s World History in 1890s Japan” explores how an American world history text—read, interpreted, and used in an entirely unintended context—shaped what we now see as a quintessentially Japanese concept, the Way of the Samurai. William Swinton’s influential textbook, Outlines of the World’s History, was widely read in Japan in the 1890s in English and Japanese translation. Proponents of the new and evolving idea of Bushidō (the Samurai code) found Swinton’s discussion of European chivalry particularly useful and, borrowing from his text, challenged what they saw as the immoral “woman worship” of the West. Thal argues that Swinton’s textbook gave rise to a Japanese conception of chivalry without women that posited an inherently male-supremacist national spirit with a mission to civilize Japan and, for some proponents, the world.

In “Gulistan in Black and White: The Racial and Gendered Legacies of Slavery in 19th-Century Qajar Iran,” Leila Pourtavaf (York Univ.) uses the late Qajar Iranian court and harem as a historically specific site through which to examine the complex and diverse histories of slavery within the region in the 19th century. Pourtavaf is particularly attentive to how hierarchies of race, gender, and sex functioned as constitutive elements of this institution. She also zooms in on the lives and afterlives of two eunuchs, Aziz Khan and Agha Bahram, who were part of the servant class of Gulistan Palace during Nasir al-Din Shah’s reign, and whose life trajectories offer further insight into the racial and gendered legacies of late 19th-century slavery in Iran.

The AHR History Lab opens with two interventions into digital history. In “The Coded Language of Empire: Digital History, Archival Deep Dives, and the Imperial United States in Cuba’s Third War of Independence,” Kalani Craig, Arlene J. Díaz, and David Kloster (Univ. of Indiana Bloomington) develop and deploy what they term Mixed-Method Approaches to Collaborative History (MMATCH) that blends more traditional close readings with digital tools including computational text analysis to explore the language of empire and the struggles for Cuban independence from 1895 to 1898 from both American and Cuban perspectives. They also reflect on what it means to undertake a collaborative historical research project with nontraditional methods, foregrounding the importance of overlapping interpretative dialogue with each other around sources and methods for successfully realizing their project. Jo Guldi (Emory Univ.) in “Text Mining for Historical Analysis” examines the importance of several recent developments in computational analysis and the use of big data for historians: efforts to understand structural silences and biases in the archive around the histories of race, gender, and the postcolonial; explorations of causality in changing language usage over time; and emergent efforts to develop a theory of text mining for the discipline.

A forum on “Globalizing Publics” is also a part of the June History Lab. Organized by Valeska Huber (Univ. of Vienna), it brings together 10 historians to discuss the modes of public-making pursued by historical actors such as journalists, writers, educators, translators, radio listeners, theater producers, and activists from varying political positions and regions of the world. Along with Huber, Emma Hunter (Univ. of Edinburgh), Nile Green (Univ. of California, Los Angeles), Ismay Milford (Freie Univ. Berlin), Sophie-Jung Kim (Freie Univ. Berlin), Su Lin Lewis (Univ. of Bristol), Sarah Bellows-Blakely (Freie Univ. Berlin), Ali Karim (Univ. of Calgary), Katharina Rietzler (Sussex Univ.), and Lea Börgerding (Freie Univ. Berlin) explore the often fragile and contingent practices through which these historical actors have sought to “globalize” publics, as well as what it means to do more public-facing work ourselves as historians. As Glenda Sluga (Univ. of Sydney) writes in her comment, the forum helps us appreciate the kind of public-making history can do “across the linguistic, cultural, and geopolitical borders that define our discipline . . . and to what global ends.”

The June History Lab includes two new modules for the #AHRSyllabus project. In “Teaching How Official History Is Made: State Standards as Primary Sources,” Stephen Jackson (Univ. of Kansas), the 2023 recipient of the AHA’s Eugene Asher Distinguished Teaching Award, traces the controversial rise of state standards over the last decade for K–12 education and offers teachers a flexible lesson plan that encourages them to draw on the history standards in their own states to help students better understand the complexities of how local constructions of official knowledge are made. Rebecca Earle’s (Univ. of Warwick) “How to Teach an AHR Article” offers a lesson plan for teaching her own 2010 AHR article “‘If You Eat Their Food . . .’: Diets and Bodies in Early Colonial Spanish America,” which is among the journal’s all-time top 10 most downloaded articles. Earle reflects on how she came to write the article and why she wanted to pay attention to the history of food. She also provides a set of primary documents from the 15th through 17th centuries and guiding questions that allow students to undertake a deep dive into the significance of food for early modern colonists in Spanish America and their understandings of bodily health.

A History Unclassified essay closes out the June edition of the Lab. In “Grassroots Archives,” Daniel McDonald (Univ. of Oxford) considers the opportunities and challenges of using social movement archives to democratize the study of history. He reflects on an effort to preserve the memory of the activism in São Paulo’s urban peripheries during Brazil’s civil-military dictatorship (1964–85) in which he took part, and what this effort reveals about preserving at-risk historical sources, enhancing local capacity, and broadening the practice of history beyond the academy.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.