Editor’s Note: This is the second installment in a two-part column. The first installment can be found here.

Hundreds [of] dirty lousey [sic] destitute Mexicans arriving at El Paso daily will undoubtedly bring and spread typhus unless a quarantine is placed at once. The City of El Paso backed by its medical board and state federal and militia officials feel that the government should put on a quarantine.

—Telegram from El Paso Mayor Tom Lea to the US Surgeon General, 1916

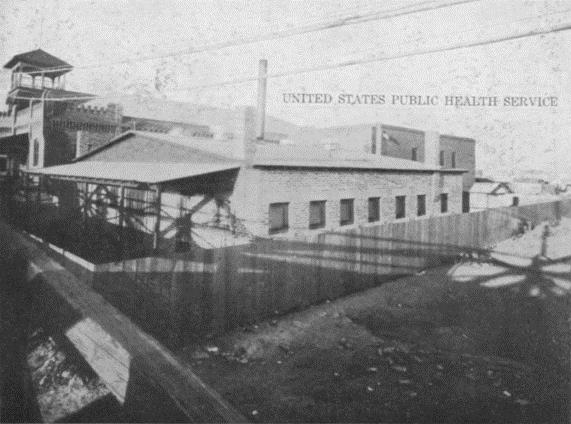

On the morning of January 28, 1917, Carmelita Torres boarded the trolley that carried her from her home in Juárez, Mexico, to work in El Paso, Texas. At 7:30 a.m., the trolley stopped at the Santa Fe Street International Bridge. There, customs officials asked all Mexicans to exit the trolley and make their way to the disinfection plant, a two-story brick building that housed screening processes to determine eligibility to enter the United States.

The disinfection plant at Santa Fe Street International Bridge was part of a larger public health infrastructure that assumed immigrants brought disease with them across the border. C. C. Pierce, “Combating Typhus Fever on the Mexican Border,” Public Health Reports 32, no. 12, March 23, 1917 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office), 427.

Rather than comply with another round of mandated disinfection and inspection, Torres exited the trolley and convinced 30 other women to protest the humiliating process. After just an hour, the crowd grew to more than 200 protestors, and soldiers from nearby Fort Bliss were sent to break up the growing protest. But the women doubled down—they laid down on the tracks and they hurled insults at custom officials. They even reportedly clawed the trolley motor controllers from the hands of the motormen, effectively halting all bridge traffic for the day. Known as the Bath Riots, this event was much more than the refusal of a bath. It was a statement against the medicalized violence imposed on racialized bodies on the US-Mexico border.

Built in 1910, the Santa Fe Street Bridge plant “disinfected” Mexicans well into the 1920s and ensured that Mexicans were clean enough to work in the United States. More specifically, it ensured they wouldn’t carry any perceived pathogens into the homes of wealthy El Pasoans who relied on Mexican domestic labor, inspecting, on average, 2,830 people a day. The disinfection process, overseen by the United States Public Health Service (USPHS), began with corralling Mexican border crossers into sex-segregated lines. Crossers were then forced to strip naked so their clothing could undergo a chemical bath. USPHS agents then inspected each head for lice. Men with lice had their head shaved on the spot, while women were given a mixture of kerosene and vinegar to apply to their scalps. Then came the bath. Everyone was sent to showers to be sprayed with soap, kerosene, and water, and later, disinfectant Zyklon B. After the body was cleaned according to USPHS standards, clothes and certificates of disinfection were distributed. Entry, however, could still be denied based on perceived physical and mental deficiencies.

The plant ensured they wouldn’t carry any perceived pathogens into the homes of wealthy El Pasoans.

In the words of El Paso historian David Dorado Romo, “1917 was a bad year for the border.” Over that year, resentment toward nonwhite immigrants developed into institutional practices that justified and normalized racism in the name of public health. The ongoing Mexican Revolution (1910–20) and typhus outbreak of 1916 had already caused El Paso mayor Tom Lea and the white elites to advocate for closing the border and implementing a quarantine of ethnic Mexicans in Juárez and El Paso. The Immigration Act of 1917 solidified the perceived differences between Mexicans on both sides of the border and the white elite. It also mandated and justified exclusion based on perceived contagion, a preexisting practice at the US-Mexico border that now had broader support.

Of course, the connection between public health and race is not specific to the Santa Fe Street Bridge or to the early 20th century. As Natalia Molina and Nayan Shah have argued, public health and racial formation have been intertwined throughout American history. Alexandra Minna Stern has even discussed this history in the specific context of the Santa Fe Street Bridge, arguing that ports of entry at the El Paso-Juárez border were physical sites of containment, processing, and violence that became a normalized part of the borderland landscape. Disinfection plants marked the border as a line between clean and unclean, between inclusion and exclusion. Discourse around cleanliness and contagion from nonwhite immigrants justified medicalized racism, determining who was and was not capable of social inclusion.

These ideas and practices, however, are not restricted to the past. The Santa Fe Street Bridge is one of the busiest ports of entry in the United States today. Customs and Border Protection agents still screen each border crosser for their admissibility to the United States. Though baths are no longer required, the institutional infrastructure that required thousands of people to undergo daily disinfection remains.

Disinfection plants marked the border as a line between clean and unclean, between inclusion and exclusion.

The COVID-19 pandemic revealed that legislation allowing mass medicalized violence is not a remnant of the past. These policies and practices have simply taken on new forms that serve present-day needs. In May 2022, a federal judge in Louisiana blocked President Joe Biden’s plan to end Title 42, a Trump-era COVID-19 related public health order that restricted immigrants from crossing the southern border. Texas governor Greg Abbott praised the ruling for curbing immigration. To Abbott, Title 42 was a positive step toward preventing the entry of “hundreds of thousands of illegal immigrants [who] remain at our southern border ready to flood into Texas.” And indeed, although Title 42 was initially invoked in March 2020 due to COVID-19, it has proved an effective tool for restricting the asylum process—essentially halting the process altogether. In addition to Title 42, a 2021 ruling ordered the Department of Homeland Security to restart the Migrant Protection Protocols, commonly referred to as “Remain in Mexico,” which requires that immigrants seeking entry to the United States must stay in Mexico while their US removal proceedings are pending. As a result of both rulings, Juárez has become America’s waiting room for immigrants from Mexico, Venezuela, Central America, Cuba, and Haiti. Between March 2020 and February 2022, US Customs and Border Protection reported more than 1.7 million Title 42 expulsions, despite the Center for Disease Control and Prevention saying that Title 42 was no longer necessary to combat COVID.

In April 2022, I embarked on my first flight since the pandemic. As I checked in at Los Angeles International Airport, it was hard to ignore the excitement from fellow travelers. People of all ages were headed across the country and across the world. I was particularly interested in the young couple in line ahead of me, buzzing about their adventure plans as they had their passports checked. Their destination? Caracas, Venezuela. I felt immediately uneasy. Here they were, here I was, casually going through LAX like the world was open. Well, it was—for us. This couple could travel back and forth as they pleased. I could travel as I pleased. As can my dad, an employee at a binational organization, who frequently crosses to and from Juárez as a part of his daily routine. At the same time, Title 42 forces asylum seekers to stay in Mexico, a mere 15-minute drive from my childhood home, for a hearing that would not happen anytime soon.

While Title 42 may have served some sort of initial purpose to combat COVID, it doesn’t anymore. As Abbott alluded, it is now an effective immigration policy that can be deployed in the name of public health. But as the Santa Fe Street Bridge shows, border restrictions that came with COVID-19 are part of a much longer history of medicalized exclusion that has allowed the United States to justify the removal of racialized bodies.

Arabella Delgado is a PhD student in American studies and ethnicity at the University of Southern California. She tweets @ArabellaDelgado.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.