This year the staff at Appomattox Court House National Historical Park wanted the 150th anniversary commemoration of the Confederate surrender to Union troops at the end of the Civil War to look different than the previous large commemorations in 1965 and 1990. The 100th and 125th events were largely “white” events, with white people commemorating a white-only history. Arguably, white northerners and southerners even found reconciliation and comfort in that exclusive history. But how could the 150th commemoration be done differently so that it speaks to African Americans as well as white people?

During the summer of 2013, Chris Bingham, a seasonal interpreter, began reviewing more than 10,000 service records of the men that made up the seven United States Colored Troop (USCT) regiments at Appomattox on the morning of April 9, 1865. He determined that about 5,000 of them were present at Appomattox on that historic morning. Besides the black servicemen present at the surrender, more than 50% of the population of Appomattox was of African descent, and mostly enslaved. So, interpretations from a black perspective would not be “forced” but critical to understanding the history of Appomattox.

In January 2014, the park began sharing the progress of Chris’s research with the Carver-Price Legacy Museum in Appomattox. The museum is dedicated to preserving and telling the black perspective as part of the American story. Thus was born a partnership between the park and the stewards of the black history in Appomattox. Park staff and members of the museum formed the “1865 Committee,” which began meeting every two weeks to discuss Appomattox’s history in an inclusive way and, perhaps more importantly, to grow the relationship between the two organizations, which had come together over the shared history of the USCTs.

In the early months, the committee members did not know exactly what they were there to accomplish, but everyone seemed instinctively to know that with the 150th only a year away, there was an important opportunity at hand. Ora McCoy of Carver-Price, a catalyst for the committee, and I would often say after a meeting, “We are not sure what to do next, but let’s meet again in two weeks.” We kept meeting regularly, and as we had more honest discussions about the park’s reputation within the black community, a trust that had not been there for some, began to grow. The park admitted the shortcomings of its past efforts to engage the community. It wasn’t that individuals at the park didn’t want to engage or didn’t try; the problem was that nothing we tried really seemed to bring in more black visitors. More interpretation (new exhibits, living history, and ranger programs) from the “black” perspective did not help. At the same time, the 1865 Committee members from Carver-Price admitted that the black community was largely unaware of the role that African Americans played in 1860s Appomattox, or even in the war as a whole. I was surprised to learn that not everyone had seen the movie Glory, and some didn’t even realize there were black soldiers in the Civil War. Thanks to Chris’s research, we were learning together that 5,000 USCTs were an integral part of the surrender story. But how would we communicate that to the community?

It was serendipitous that in July 2014 the park engaged in making a new educational film that would be released for the 150th anniversary. Unlike the two older (1970s) programs that it would replace, this film included more information about the village where the surrender unfolded, its demographics, and dependence on slavery. It also shed light on the USCT presence, the Lincoln assassination that followed, and emancipation as a legacy of the war—none of which were in the older films. To more accurately depict village life and the role of the USCTs, the partnership between the park and the museum bore fruit as together we reached out to the black community, and more than a dozen of its members came out to portray villagers and soldiers in the new film.

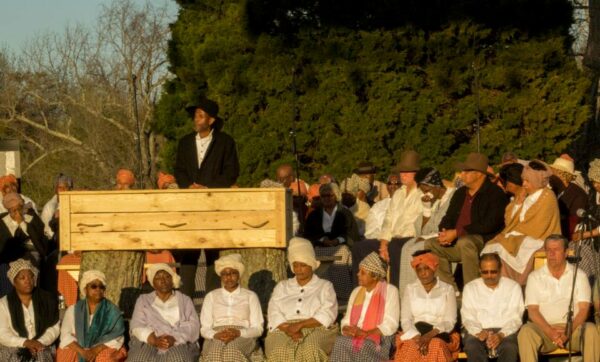

Despite this productive partnership, we could not yet envision what it would contribute to the 150th. During the discussions at our bi-weekly meetings, however, we talked about the only known civilian casualty of the fighting at Appomattox: an enslaved woman named Hannah Reynolds. The group came up with the idea of reenacting Hannah’s funeral as part of the 150th commemoration. There was tremendous excitement at the possibilities, and good ideas began to multiply. We decided to call the program “Footsteps to Freedom,” and that it would be both a living history program and a commemoration. The objective of the 150th anniversary commemoration would thus be twofold: to involve the black community in park activities and to establish emancipation (though not freedom) as one of the legacies of the surrender.

The living history program that resulted was a simple, typical, outdoor 1860s funeral consisting of a preacher, family members, pallbearers, and a small choir. The service reflected influences of distinctly African burial traditions such as dancing and wailing. There was a horse-drawn wagon and coffin that was nailed shut as part of the service. Other commemorative elements included an introduction by a park ranger and a 100-person choir of members from black churches all over the area singing spirituals before the funeral (and “Amazing Grace” afterwards).

After the service, 4,600 luminaries were lit throughout the village. Each light represented a person in Appomattox County who was emancipated as a result of the surrender. One light belonged to Hannah, who, though mortally wounded on April 9, didn’t die until April 12, an emancipated woman.

Luminaries line the road through Appomattox Court House Historical National Park, symbolizing each person from Appomattox who was emancipated at the end of the Civil War. Photo by National Park Service.

Only time will show what impact this partnership will have on race relations in Appomattox and beyond. At the park, however, we learned that it is not enough to want to have inclusive history, and it’s not enough to create interpretation for a minority community. What actually got African Americans in the park was doing interpretation with their community. What can also be said now with certainty is that the 150th at Appomattox looked very different than the 100th and 125th anniversaries.

grew up around Lynchburg, Virginia. After graduate school he taught English in South Korea before beginning a career with the National Park Service. He has lived and worked in Appomattox since 2008 as the chief of education and visitor services at the park.

This post first appeared on AHA Today.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.