A federal survey of faculty at U.S. colleges and universities in 2004 found real increases in the number of history faculty employed, as well as proportional increases in the number of historians employed on the tenure track and full time. Unfortunately, even as historians’ employment prospects improved, the survey shows that average salaries for historians fell further behind most other academic disciplines and the demographic diversity of the profession was largely unchanged.

According to newly available data from the National Survey of Postsecondary Faculty, the latest in a series conducted at roughly five-year intervals by the U.S. Department of Education and published recently, an estimated 29,220 historians were employed at two- and four-year colleges and universities in fall 2003.1 This marked an increase of almost 15 percent from the previous survey, which estimated that 25,470 historians were employed in fall 1998. History faculty constituted approximately 2.41 percent of the 1.21 million faculty employed in American colleges and universities in fall 2003, which marked a modest increase in the proportion of faculty teaching history—up from 2.37 percent in fall 1998 and 2.31 percent in fall 1992.

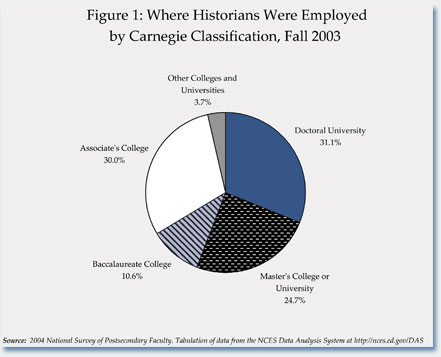

The largest proportion of historians were working at doctoral universities, but only by a narrow edge over faculty at two-year colleges (Figure 1). With 31.1 percent of academic historians at doctoral institutions, history lagged behind the average for all fields. According to the survey, 37.4 percent of all faculty were employed at doctoral universities. The difference was primarily in larger proportions of history faculty at other types of four-year colleges and universities, as 24.7 percent were employed at institutions that confer the master’s degree (compared to 20.6 percent of faculty in all fields), and another 10.6 percent were at baccalaureate institutions (compared to an average of 7.3 percent). History was near the average in the proportion working at colleges that confer associate’s degrees, which account for 30 percent of faculty in the field.

The largest proportion of historians were working at doctoral universities, but only by a narrow edge over faculty at two-year colleges (Figure 1). With 31.1 percent of academic historians at doctoral institutions, history lagged behind the average for all fields. According to the survey, 37.4 percent of all faculty were employed at doctoral universities. The difference was primarily in larger proportions of history faculty at other types of four-year colleges and universities, as 24.7 percent were employed at institutions that confer the master’s degree (compared to 20.6 percent of faculty in all fields), and another 10.6 percent were at baccalaureate institutions (compared to an average of 7.3 percent). History was near the average in the proportion working at colleges that confer associate’s degrees, which account for 30 percent of faculty in the field.

As these findings indicate, this survey is particularly valuable because it provides a rare window into the employment and work conditions of historians at both two- and four-year institutions. The data we typically report in Perspectives—drawn from departments listed in the AHA’s Directory of History Departments—consists disproportionately of four-year institutions with discrete departments of history. So the federal survey allows us to look at trends affecting all historians in academia and compare them to faculty in other disciplines.

Sharp Increases in History Faculty

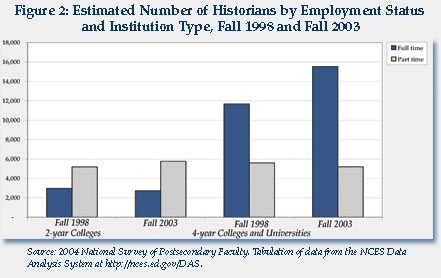

Perhaps the best news in the survey is a sizeable increase in the number of historians employed full time. The proportion of full-time faculty among all historians employed in academia grew from 57.6 percent in the fall of 1998 to 62.5 percent in fall 2003. This increase is in contrast to the decrease (albeit slight) in the proportion of full-time faculty in all fields, from 57.4 to 56.3 percent over the same span. It should be noted, however, that the growth in full-time history faculty occurred exclusively at four-year colleges and universities.

In real terms, the number of faculty reported as employed full time at four-year institutions increased by almost one-third—rising from approximately 11,680 historians employed full time in fall 1998 to 15,537 in fall 2003 (Figure 2). The increase in the number of full-time faculty indicated by the federal survey is greater than the increase shown by our tabulations of faculty listed in the Directory of History Departments, which have shown modest but steady growth in recent years.2 The growth is even more pronounced when viewed in comparison to other fields, as the federal data indicates that history was one of the fastest growing fields, lagging behind just four of the 26 disciplines in their survey. Among all fields, the average growth was only 12 percent.

In real terms, the number of faculty reported as employed full time at four-year institutions increased by almost one-third—rising from approximately 11,680 historians employed full time in fall 1998 to 15,537 in fall 2003 (Figure 2). The increase in the number of full-time faculty indicated by the federal survey is greater than the increase shown by our tabulations of faculty listed in the Directory of History Departments, which have shown modest but steady growth in recent years.2 The growth is even more pronounced when viewed in comparison to other fields, as the federal data indicates that history was one of the fastest growing fields, lagging behind just four of the 26 disciplines in their survey. Among all fields, the average growth was only 12 percent.

At the same time, the data indicates that the number of historians employed part time at four-year institutions fell a bit more than 7 percent in real terms, from 5,600 in 1998 to 5,193 in 2003. As a result of these divergent trends, the proportion of history faculty employed part time at these institutions fell from 32.4 to 25.1 percent of the departmental faculty, reversing a trend that extends back more than two decades.

In contrast to the trend at four-year institutions, the growing use of part-time faculty at two-year colleges continued along its earlier trajectory. The estimated number of historians employed full time at those institutions fell 8.4 percent (from 2,970 in 1998 to 2,721 in 2003), while the number of part-time faculty rose 11.2 percent (from 5,190 to 5,769). This continued trends from the previous survey of faculty employed in fall 1992.

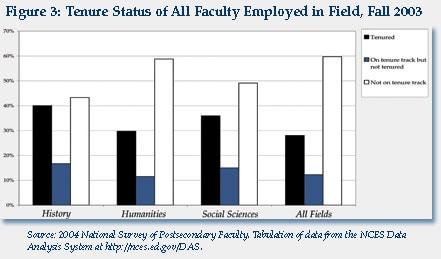

Of course, just because someone is working full time does not mean the job is more secure. The growth in part-time employment during the 1990s coincided with a growth in the number of positions off the tenure ladder. In a 1981 survey of faculty in two- and four-year programs, the AHA found that 91.4 percent of the faculty in history departments were either tenured (78.9 percent) or on the tenure track (12.5 percent).3 According to the new survey, in fall 2003 just 56.7 of the history faculty in two- and four-year colleges and universities were employed on the tenure ladder—as 40 percent held tenure, and 16.7 percent were on the tenure track. Although the numbers were down significantly from 1981, the new survey does offer some positive news, as this represents an improvement from the fall of 1998, when barely 51 percent of historians held tenure or a position on the tenure track.

Moreover, the proportion of history faculty on the tenure ladder was unusually high in comparison to other disciplines. Among all fields, barely 40 percent of faculty were on the tenure ladder, with 28.0 percent holding tenured appointments and 12.2 percent on the tenure track (Figure 3). Among the humanities fields (which includes history), only 41.3 percent were on the tenure ladder, while in the social sciences, just 50.9 percent of the faculty have or could earn tenure.

Moreover, the proportion of history faculty on the tenure ladder was unusually high in comparison to other disciplines. Among all fields, barely 40 percent of faculty were on the tenure ladder, with 28.0 percent holding tenured appointments and 12.2 percent on the tenure track (Figure 3). Among the humanities fields (which includes history), only 41.3 percent were on the tenure ladder, while in the social sciences, just 50.9 percent of the faculty have or could earn tenure.

If we limit our analysis just to faculty who were employed full time, the gap between history and other disciplines becomes a bit more pronounced. In the fall of 2003, 60.4 percent of the full-time history faculty held tenure, while another 25.7 percent held tenure-track appointments. With 86.1 percent of its full-time faculty either tenured or on the tenure track, history was second only to political science in the proportion of full-time faculty with tenure-ladder appointments. The average for all fields was just 68.1 percent, with 47.5 percent tenured and 20.6 percent on the tenure track.

The estimated number of historians employed full time with tenure grew from 9,155 in 1998 to 11,020 in 2003, while the estimated number on the tenure track grew from 3,037 to 4,696. The number of full-time faculty employed off the tenure track also increased, but much more slowly, from 2,458 to 2,544.

As the high proportion of tenured faculty in history suggests, our discipline had an unusually large segment of faculty in the associate and full professor ranks. Looking broadly at faculty employed at all institution types, 22.8 percent of history faculty held the rank of professor and 17.6 percent held the rank of associate professor. History had the ninth largest proportion of faculty in the upper ranks, which positioned us among the hard science and social science fields.

Further Evidence of Lagging Salaries for Discipline

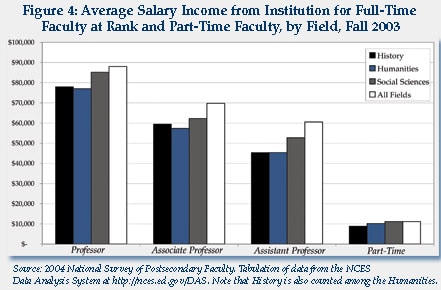

In contrast to the trends in employment, the news on historians’ salaries was not nearly as positive. The survey shows history is losing ground relative to the rest of the academy, particularly at the assistant professor level. The estimated average salary for history faculty employed full time in calendar year 2003 was $60,717—10 percent below the average ($67,796) for faculty in all fields.

This actually understates the gap for most historians, since the average was pushed up by the higher proportion of full professors in history than in other fields noted above. When we make a rank-by-rank comparison, we find history lagged further behind at every rank and the gap grows progressively wider at each step down (Figure 4).4 Full professors in history earned 11.5 percent below the average for faculty at that rank ($77,948 as compared $88,041 in all fields). At the associate professor level the gap grows to 14.8 percent ($59,461 compared to $69,769), and expands further to a 25.2 percent gap for assistant professors in the field ($45,328 compared to $60,570). It seems reasonable to assume that as those assistant professors move up the ranks, their salaries will be hobbled by this poor start, pulling down average salaries for the field in the future.

This actually understates the gap for most historians, since the average was pushed up by the higher proportion of full professors in history than in other fields noted above. When we make a rank-by-rank comparison, we find history lagged further behind at every rank and the gap grows progressively wider at each step down (Figure 4).4 Full professors in history earned 11.5 percent below the average for faculty at that rank ($77,948 as compared $88,041 in all fields). At the associate professor level the gap grows to 14.8 percent ($59,461 compared to $69,769), and expands further to a 25.2 percent gap for assistant professors in the field ($45,328 compared to $60,570). It seems reasonable to assume that as those assistant professors move up the ranks, their salaries will be hobbled by this poor start, pulling down average salaries for the field in the future.

The salary gap for history faculty employed part time was comparable to that for full-time faculty. Historians employed part time earned an average of $8,852 from the college or university employing them—21 percent below the average for all fields, making history the fourth lowest discipline. This appears to be at least partially a function of part-time history faculty teaching fewer courses (the survey does not tell us whether this was due to faculty choice or a smaller number of courses available). On a per course basis, historians earned an average of $1,749 per class, just 5.7 percent below the average for all fields.

This income gap between history and other fields grows much wider when we take all income into account—including income from book royalties, consulting, and other activities. In calendar year 2003, full professors in history lagged 12.1 percent behind the average for all fields, earning an average of $90,900, and the gap again grew progressively larger at the next two ranks down. Associate professors in history earned an average of $65,177 (21.6 percent below the average in all fields), while assistant professors earned $50,316 (29.9 percent below the average).

Looking at the total incomes also casts in starker relief the enormous financial advantage that full-time faculty enjoy. Among history faculty with PhDs, there was a 25 percent gap in total income between those who were employed full time and those employed part time. History PhDs employed full time earn an average of $81,165 per year from all sources, while those employed part time (that is, those teaching part time in history departments while earning their living in other full-time positions) earn an average of $63,421. When we look more narrowly at those who indicated that their part-time employment was their “primary job activity,” the average total income falls to $33,402. While one might assume that the discrepancy between the average salary of full- and part-time faculty could be attributed to differences of age and time in service to the institution, the gap remains fairly consistent when analyzed by these other factors.

High Job Satisfaction Despite the Salaries

Despite the lagging salaries in the field, historians in academia—including faculty working part time who would have preferred full-time employment—report high levels of job satisfaction.

Historians employed full time reported a higher average level of job satisfaction than faculty in other fields. Full-time faculty in the social sciences were moderately less satisfied than faculty in other fields while humanities faculty were slightly more satisfied, but these were all within a fairly narrow range. Notably, among full-time faculty in all fields, the highest level of dissatisfaction could be found at the associate professor level.

Well over 80 percent of full-time history faculty said they were satisfied with their current jobs. Almost 50 percent of the full professors reported they were “very satisfied” with their jobs, as compared to 44.4 percent of the faculty at the assistant professor level. In history, only 37.0 percent of associate professors said they were “very satisfied” with their jobs.

History faculty employed part time reported slightly higher levels of dissatisfaction, but again, their average rating of job satisfaction was very close to the rating for full-time faculty in the field, and even just a bit better than associate professors in the field. Among history faculty employed part time, 56.3 percent reported they were “very satisfied” with their jobs—a mark higher than among any of the full-time faculty ranks. However, because a large proportion of part-time faculty reported they were “very dissatisfied” with their job (at the other extreme of the scoring range), the average level of satisfaction among part-time faculty is lower than the average for full-time faculty.

As we have noted in previous reports, faculty teaching part time do so for a variety of reasons and under a variety of conditions. The common perception of part-time faculty tends to be of someone carrying a number of these underpaid positions to eke out a living. However, past AHA surveys and evidence in the federal survey indicate that a majority were doing so as an avocation, either in combination with a full-time job or after retirement from full-time teaching. Not surprisingly, the part-time faculty who would have preferred a full-time appointment reported lower levels of job satisfaction, as just 37.7 reported they were “very satisfied,” though another 45.3 percent said they were “somewhat satisfied.”

The differences in reasons for teaching part time help explain another anomalous finding in the survey, which shows that full-time faculty were more likely to doubt that part-time faculty were being treated fairly than part-time faculty in the same discipline. In history, 47.1 percent of the full-time faculty disagreed with the statement that “part-time faculty are treated fairly” at their institution, as compared to 32.7 percent of part-time faculty in the field. It should be noted, however, that while fewer part-time faculty perceived unfair treatment than their full-time colleagues, the proportion indicating some mistreatment was almost 25 percent higher than the average among part-time faculty in all fields—the fifth highest among the disciplines.

One of the other markers of satisfaction can be found in responses to the question whether a particular faculty member would choose an academic career again. Among full-time faculty, just over 94 percent of historians—second only to law faculty—said they would choose the same academic career path again; this assessment was consistent among history faculty at every rank except the instructor level. In contrast, among part-time faculty in history, just 85.6 percent said they would choose an academic career again—the fourth lowest among 26 disciplines.

Demographics of History Faculty

As we have noted in recent reports on students receiving degrees, history seems to be unusual in the limited number of women and minorities earning degrees in the field.5 It is hardly surprising, then, that the faculty teaching them reflect and perhaps reinforce this trend.

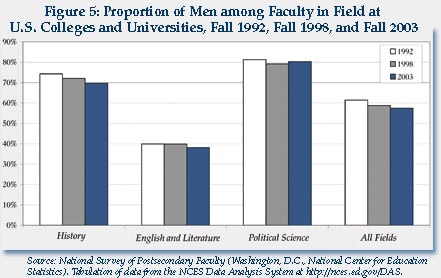

The proportion of women teaching history grew slightly, from 27.9 percent of the faculty in 1998 to 30.4 percent in 2003. As indicated in Figure 5, this was in line with the previous trend in the field. Nevertheless, history had the seventh smallest proportion of women of the 26 fields in the survey, as women comprised 42.5 percent of the faculty in all fields.

The proportion of women teaching history grew slightly, from 27.9 percent of the faculty in 1998 to 30.4 percent in 2003. As indicated in Figure 5, this was in line with the previous trend in the field. Nevertheless, history had the seventh smallest proportion of women of the 26 fields in the survey, as women comprised 42.5 percent of the faculty in all fields.

An important part of this change is generational, as increases in the proportion of women earning history PhDs over the past three decades were reflected in the proportion of faculty teaching. Women account for just 24.5 percent of the historians over the age of 55 and 37.1 percent of those under the age of 45. Even in the younger cohort, however, women still comprise a smaller proportion of the history faculty with PhDs than their representation among history PhDs earned over the past 15 years (where it has hovered around 40 percent).

The proportion of minorities among surveyed history faculty was so small that the data analysis system of the Department of Education will not provide more specific calculations that will allow us to draw useful conclusions. The proportion of white history faculty was closer to the average for all fields, as 85.3 percent of history departments were identified as white as compared to 82.5 percent of faculty in all fields. This was essentially unchanged from 86.2 percent of history faculty in fall 1998. The survey estimates that 1.4 percent of history faculty were American Indian or Alaska Natives, 5.4 percent were Asian American, 4.9 percent were African American, and 3.0 percent were Hispanic.

One other notable trend in the demographics of historians in academia was a modest decrease in their average age relative to other disciplines. In the 1999 survey, history faculty had the highest average age of any discipline in the survey at 51.8 years. In the latest survey that has fallen to 50.5 years—still a full year above the average for all fields, but falling to sixth among the disciplines in the survey.

This report only scratches the surface of the rich array of data offered by the survey. In the coming months we will offer more focused examinations on the status of women and minorities and the different practices in teaching and the use of technology in our field.

Notes

- The survey is based on a random sample of 35,629 faculty at 1,080 two- and four-year institutions, with a weighted response rate of 75.6 percent. This data was used as a sample to provide estimates about the larger faculty population. For more information on the survey methodology see https://nces.ed.gov/surveys/nsopf/. The tabulations for this report were drawn from data runs taken from the National Center for Education Statistics web site at https://nces.ed.gov/dasol/tables/. [↩]

- See, for instance, the most recent job market article in the January issue of Perspectives. [↩]

- Survey of the Historical Profession, Academia: 1980–81 (Washington, D.C.: American Historical Association, 1981). [↩]

- We exclude the instructor and lecturer positions from our analysis because they include a wide range of different employees under the same title, with senior faculty in visiting positions as well as entry level faculty who are still ABD. This produced an unusually wide range of results and severely skews the data. [↩]

- Robert B. Townsend, “Rising Tide of History Undergraduates Contrasts with Declining PhDs,” Perspectives (December 2005), 8. [↩]