Élise Franssen, a Belgian postdoctoral researcher, and Frédéric Bauden, a professor at the University of Liège, are creating an online database of paratextual elements in Arabic, Turkish, and Persian manuscripts in order to track the transmission of Middle Eastern books. By doing so they aim to learn about the histories of public and private libraries, patrons of manuscripts, the geographic circulation of books, and the reading practices of individuals and communities.

Paratextual elements include marks that owners wrote into the manuscript (including their names and the dates of purchase) and waqf statements, which indicate that the owner of the book donated it to a religious charitable endowment. Some books contain notes from the authors stating that they had reviewed the copy of the book and approved it, while some book owners make notes about those who read or borrowed the manuscript as well.

In a talk at the Middle East Studies Association annual meeting in Washington, DC, Franssen stated that studying the paratextual elements in manuscripts provides information about scholars’ collections and the practice of selling entire libraries in the medieval period. Additionally, “Having samples of scholars’ handwriting would help researchers in paleography and assist in the identification of autograph or holograph manuscripts,” Franssen said.

The project, funded by the Fonds de la Recherche Scientifique, is in the process of being developed at the University of Liège with the help of two computer specialists who also have backgrounds in literary studies. Other scholars, specialists in Persian and Ottoman manuscripts, will verify the readings of marks and participate in their entry into the database. Others, especially curators of important collections of Arabic manuscripts, will serve as consultants.

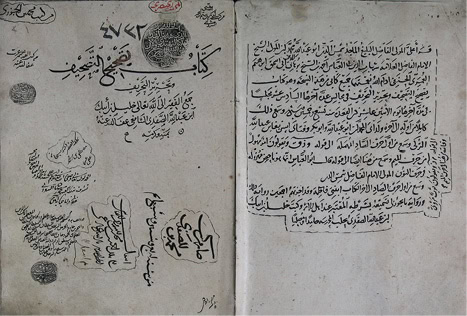

In a manuscript from the Süleymaniye Library (Ms Ayasofya 4732), in the hand of Al-Safadi, various ownership marks, stamp impressions, a waqf statement, and an autograph sama can be found.

The database will include the price of the manuscript, if it is mentioned on the manuscript’s pages, as well as photographs of autographs, author handwriting, and any other marginal notes. It will complement the information found in the Islamic seals database of the Chester Beatty Library, which is also accessible online (www.cbl.ie/islamicseals/Home.aspx).

Franssen provided examples of what researchers might find through a systematic study of paratextual elements in Islamic manuscripts. In the case of 450 Mamluk-period manuscripts held at the Süleymaniye Library in Istanbul, a particular book collector, Al-Shirwani, emerges as a prominent name. Al-Shirwani, who died in 1723, was a civil servant of the Ottoman state. Franssen also discovered that the son of the famous author Al-Safadi, who is said to have written about 50 books, among them the important biographical dictionary Al-Wafi bil-wafayat, inherited his father’s collection after his death in 1363 and decided to keep at least some of his father’s books in his library. This information was gleaned from the ownership marks the son inscribed into the manuscripts.

According to Nelly Hanna, distinguished university professor and chair of the Department of Arab and Islamic Civilizations at the American University in Cairo, the history of the book is an underdeveloped area in the field of Middle East studies. Whereas books have been studied as art—especially when they contain calligraphy and illuminations—there has been limited work on the Middle Eastern book’s history. Most libraries have not even cataloged their collections of Arabic manuscripts, she said. Therefore, this new methodology and approach will allow scholars to use sources differently; in published books, the language is often “corrected,” and therefore lost. The size and shape of a manuscript, which can tell the scholar a great deal about the uses of the book, are also lost when a book is studied in its published form rather than in manuscript. Additionally, many editors and scholars skip the marginal notes in manuscripts when they prepare a text for publication, but these notes provide valuable information about the authors and readers, as well as the scribes who copied the manuscripts.

Franssen called on other scholars of Middle East history to contribute information and photographs of paratextual materials to the database, which will be online in the spring, on the University of Liège Department of Arabic Language and Islamic Studies website (web.philo.ulg.ac.be/islamo/portfolio-item/ex-libris-ex-oriente).

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.