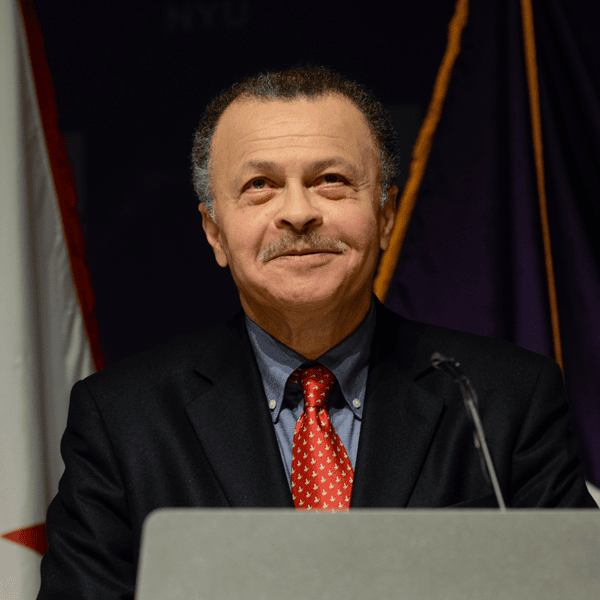

In 16 days and on the morrow of the Martin Luther King national holiday, a black man will assume the presidency of these United States as the people bid good riddance to the worst administration in their history. A civil rights dream, whose large potential will emerge only in the fullness of time, appears palpably achievable. Surely, the best professional judgments about the historical significance of the 2008 election will come with the 2012 election. It was the German philosopher Friedrich Schlegel who cautioned that historians serve the public best as prophets in reverse rather than as commentators on fast-moving current events. Arthur Schlesinger’s The Cycles of American History may offer one of the most serviceable American exemplifications of Schlegel’s maxim. As Schlesinger took his leave not quite two years ago, he assured us that the start-up of one of his 25- to 30-year cycles in the nation’s political life had begun, that the conservative ascendancy personified by Reagan and institutionalized by Rove would soon be displaced by liberal reform—idealistic but pragmatic.

Seen from this altitude, Barack Obama’s victory becomes a zeitgeist phenomenon whose campaign mantra of change was perfectly in sync with the republic’s historic oscillation between antigovernmentalism and regulatory redress—which in no way gainsays the president-elect’s superb political intelligence and becalming temperament. The problem with reading history as a cycle or, for that matter, as a consensus largely spared of extremes, or, yet again, as a linear progression interrupted by civil war and market crises, is that such grand narratives tend to swallow up the contingent or the unique in explanatory neatness. Even after the House of Representatives fell to an unstable Democratic majority in 2006, only the most sanguine historian might have expected a cyclical or Zeitgeistian capture of the White House and the Senate in 2008.

Five years ago when Paul Krugman decried the “great unraveling” of our institutions or just several months ago when Naomi Klein unmasked the rationale behind “disaster capitalism,” many must have feared that the radical right had permanently rigged the electoral game by institutionalizing a war on terror and by ginning up a putative “stakeholder society” based on painless mortgages, ceaseless credit debt, and stratospheric real estate values.

All presidential contests matter greatly, but the constitutional and public policy stakes of this last one were way up there with the pivotal election of 1860. Indeed, after their 2004 disarray, it seems no exaggeration to say that the Democrats along with their political kinfolk could have faced an ideological massacre in 2008 comparable to that inflicted on Bryan’s Democratic-Populists by McKinley’s business-financed campaign behemoth in the fateful 1896 election. In The Wrecking Crew, Thomas Frank spoke for those who feared that the progressive forces would be outgunned and outsmarted once again last November by the radical rightists. The larger vision of Rove, Tom Delay, Phil Gramm, and their like, Frank wrote, “is of a future in which liberalism is physically barred from the control room—of an ‘end of history’ in which taxes and onerous regulation will never again be allowed to threaten the fortunes that private individuals make for themselves.”

So how, against the odds of plutocracy, experience, color, class, and misconceived patriotism, has it come about that change comes to Washington in 16 days? Beyond the cycles and the other paradigms, the election of America’s 44th president is distinguished by three special, not to say unique, factors: the global; the racial; the catastrophic.

World

The first, the global, is that the 2008 election was the first U.S. election in history in which the whole world voted—figuratively. The planet was excited by Barack Hussein Obama as much for what he was as for what he said. Arguably, not since Woodrow Wilson promulgated his 14 Points have the ideals of an American politician mattered as much to the rest of the world. To observe this unprecedentedly expensive and long presidential campaign from Berlin, Paris, and London as my wife and I did during an extended European Union residency was to be instructed in an exalted European idea of American exceptionalism.

Think 250,000 Berliners in the Tiergarten waving the stars and stripes almost in desperation for a once-admired superpower. These Berliners, as did most Europeans, saw the United States’ indifference to international law and comity, military adventurism, and self-fulfilling policies of a civilizational shootout as the major source of the rising tide of religious, cultural, and security crises threatening to engulf them. Granted, popular opinions abroad were fueled by long pent-up resentments and schadenfreude. No matter that a Turkish chancellor of Germany, an Algerian president of France, or a Pakistani Prime Minister at Downing Street was not even a EU fantasy, Europeans, Asians, Africans, Indians, Chinese, Latin Americans, and Canadians claimed that Barack Obama’s election was America’s last chance to regain global respect and retain geopolitical leverage. And to a great many Americans these concerns really mattered.

Race

The second factor is the racial. W.E.B. Du Bois set the terms for American race relations a hundred years ago, famously prophesying that the color-line would be the paramount problem of the 20th century. Writing the first academic biography of Martin Luther King Jr. 40 years ago, I reasonably assumed that King’s vision would be indefinitely trumped by Du Bois’s axiom. To watch from Berlin the television fulminations of Reverend Jeremiah Wright made one expect the Obama candidacy to be fatally wounded by the hate that, until then, had dared not speak its name. Since LBJ’s presidency, the race wedge with its Bradley factors, welfare queens, and Willie Horton scarecrows had been the Democratic Party’s special curse. Then Senator Obama’s astonishing speech at Philadelphia’s National Constitution Center succeeded for the first time in American public debate in triangulating race, class, alterity, and opportunity. In proclaiming that his life story had “seared into my genetic makeup the idea that this nation is more than the sum of its parts,” the candidate turned the race wedge on itself by transforming the third rail of national politics into a causeway to American exceptionalism at its finest. In so doing, Barack Obama, the first existential president, seemed to resolve those insurmountable dilemmas of nationality and color unforgettably posed by Du Bois’s foundational text, The Souls of Black Folk.

Catastrophe

Finally, this election was probably most decisively decided by catastrophe, notwithstanding the delightful gift of Sarah Palin. Although the math in the House and Senate is gratifying to the president-elect’s ambitious change agenda, it has to be noted that 59 million Americans trudged through the carnage of Greenspanomics to pull the McCain-Palin lever. Absent the breathtakingly sudden collapse of unregulated capitalism and the GOP candidate’s eerie economic unsophistication manifested in the final campaign weeks, neither Obama’s position on the Iraq war nor his insurance prescriptions for health care might have given him a clear electoral-college victory. Fifty-five percent of whites still voted for McCain. Many more of them, plus others, would almost surely have done so. The catastrophic failure of the market caused the electorate to experience a crisis of profligacy that played to Obama’s unflappable temperament and Keynesian nostrums. In The Audacity of Hope, the president-elect proffered his readers the wisdom of Hamilton and Lincoln. Their basic insight “that the resources and power of the national government can facilitate, rather than supplant, a vibrant free market,” he wrote, “has continued to be one of the cornerstones of both Republican and Democratic polities at every stage of America’s development.” Enough of us have decided that the insights of a Hamilton and the confidence of an FDR make a replay of the New Deal imperative.