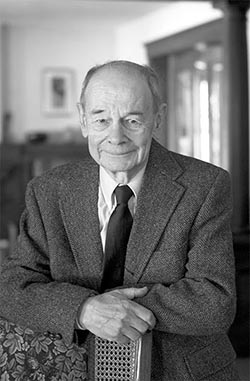

Edmund Sears Morgan. Courtesy Michael Marsland/Yale University

Edmund Sears Morgan, a quiet yet decidedly witty man, was an amazing historian whose articles and books recast the biggest topics in American history, from the Puritans to slavery to the Revolution. He helped establish colonial American history as a powerful, distinctive field within American history, personifying the field itself and what it meant to be a historian.

Born in Minneapolis, Minnesota, on January 17, 1916, Morgan received an AB at Harvard in 1937 and a PhD in American Civilization in 1942, studying with Perry Miller. He taught at the University of Chicago (1945–46), Brown University (1946–55), and Yale University (1955–86). In 1939 he married Helen Mayer, with whom he wrote The Stamp Act Crisis in 1953; she passed away in 1982. He later married the historian Marie Caskey, with whom he coauthored many review essays for the New York Review of Books. He led an exceptionally active life after retiring in 1986 and died in New Haven, Connecticut, on July 8, 2013, at age 97. Marie Morgan, daughters Penelope Aubin and Pamela Packard, six grandchildren, and seven great-grandchildren survive him.

Once he started, Morgan never really stopped writing. His first books, The Puritan Family (1944) and Virginians at Home (1952), displayed his lifelong fascination with New England and Virginia, an unstrained revisionism, and the translucent prose that attracted readers beyond professional historians. Morgan’s New Englanders embraced sex and music even as they pursued salvation with sometimes deadly purpose, and his Virginians sought pigs, plantations, and their own freedom on the backs of enslaved Africans.

The Stamp Act Crisis, which was his favorite, transformed a tax dispute into a dramatic narrative about colonists challenging Parliament. The Birth of the Republic (1956) offered a synthesis of the Revolutionary era so masterful that it has recently appeared in yet another edition (the fourth).

The Puritan Dilemma: The Story of John Winthrop (1958) fixed Morgan’s star at age 42. Morgan, who was an atheist, wrote about men and women as they were, no matter their language and ideas. Morgan’s elucidation of the Puritans’ experiment—“doing right in a world that does wrong”—made The Puritan Dilemma the most commonly assigned book in US history survey courses.

Morgan wrote a stream of books on the Puritans and the Revolution well into the 1990s: on Ezra Stiles and Roger Williams, on a key Puritan idea in Visible Saints, two books on the Revolution, one on George Washington, and a book on popular sovereignty, Inventing the People. Morgan stressed the coherence of Puritan thought, especially its continuing development in America, and the remarkable creativity and occasional shenanigans of America’s Revolutionary leaders.

Morgan’s American Slavery, American Freedom: The Ordeal of Colonial Virginia (1975) became a watershed book like The Puritan Dilemma. Through quantitative and demographic evidence, Morgan described how enslavement unified whites as it oppressed Africans, allowing farmers and planters alike to “more safely preach equality in a slave society than in a free one” and bringing on the American Revolution while deepening America’s racial tragedy.

Morgan observed that his best-selling Benjamin Franklin (2002) also might mark a watershed, but for its “geezer factor”; “there aren’t that many 86-year-olds writing books,” he said. In fact, it was a writer’s tour de force, steeped in Morgan’s mastery of Franklin’s voluminous papers and his judgments of “a man with a wisdom about himself that comes only to the great of heart.”

Morgan’s New York Review of Books essays, many written with Marie Morgan, constituted a nearly 30-year ongoing seminar for thousands of readers. Morgan went to the heart of a book. In assessing a new edition of John Winthrop’s journal, he asked, “What makes a great man great?” then laid out Winthrop’s case in a mere ten pages.

His work brought its criticism. Historians challenged Morgan’s accounts of Puritan doctrine, demographic data, characterization of Virginia’s move to slave labor as an “unthinking decision,” and appraisals of the American Revolution. But no one questioned the importance of his arguments, the breadth of his research, or the fluidity of his prose.

“Tell me what you see,” Morgan urged graduate students examining original sources. If they were surprised, he offered simple advice: “Stop right there. Ask yourself, ‘Why did I not know that?’” For Morgan’s many students, the answers often became books.

The ’70s rumor that a high school rock band had named itself The Puritan Dilemma may have been apocryphal, but Morgan’s formal awards were real: the National Humanities Medal, a Pulitzer Prize for lifetime achievement, the Bancroft Prize, presidency of the Organization of American Historians, at least nine honorary degrees, Yale’s Sterling Professorship and DeVane Medal for teaching, the American Historical Association’s Distinguished Scholar Award, membership in the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and the British Academy, and more.

Morgan was a legendary lecturer. At his final lecture in 1986, he observed, “No matter how we looked back on our Revolution, it was ‘as it always has been, good enough for us.’” Then, as one student recalled, he ended ten minutes early, closed his notes, and “bending forward one last time over his microphone, . . . bade us a quiet ‘Thank you,’” leaving the room quickly as students clapped.

Nearing retirement, Morgan took up piloting airplanes “for the hell of it,” then pursued woodworking in a basement chocked with tools, producing bowls widely admired at woodworker shows.

Morgan’s life and histories rested comfortably on his humanity, and his 1984 tribute to his then ill friend Sydney Ahlstrom expressed Morgan’s integrity as well as it described Ahlstrom’s. Morgan credited Ahlstrom with revealing “things I had never noticed or thought about.” One was the stone wall around New Haven’s Grove Street Cemetery.

I never really saw it until a year ago when you pointed it out. “Have you ever noticed what a wonderful wall that is?” you asked. And indeed I had not. The texture, the proportions, the workmanship make it a thing of extraordinary beauty. It is truly a wonder, and the awareness of it now enriches my day every time I pass. Why couldn’t I have seen it for myself? Because I lack your sense of wonder. But I can borrow yours when you offer it, and you offer it continuously.

Edmund Morgan offered students, readers, and fellow historians his own sense of wonder for more than 70 years. He is a model for generations to come.

Jon Butler

Yale University, emeritus

University of Minnesota, Twin Cities, adjunct