Editor’s Note: This is the first installment in a two-part column. The second column is available here.

When I began researching academic exchange during the Cold War, I knew that the topic was deeply personal to me. After all, I was an international student from Russia getting my PhD at an American university. What I could not have predicted was how the questions I asked in the archive would echo the questions I asked myself.

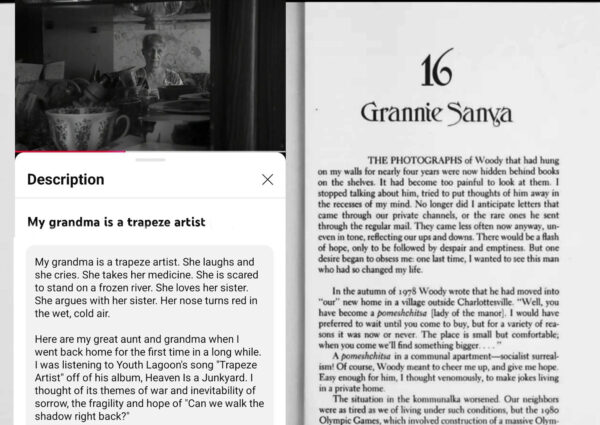

A still from Alisa Kuzmina’s video of her grandmother Nina (left) alongside Irina McClellan’s writings on her grandmother (right). Alisa Kuzmina; Irina McClellan, Of Love and Russia: The Eleven-Year Fight for My Husband and Freedom, trans. Woodford McClellan (W. W. Norton, 1989), 219.

As I researched stories of cross-cultural knowledge, I came across narratives of cross-cultural romance. These involved Soviet-American couples who navigated love, separation, and immigration policies at a time of heightened political tension. My dissertation focus shifted, and so did my life. I married an American man and experienced the complexities of immigration firsthand—a process one Soviet spouse called “a strange state called Limbo.” As I moved through the space between the life I had left in Russia and the one I was building in the United States, I read memoirs of Soviet-American couples. Their stories became not only the core of my dissertation but also inspired me to reflect on my own trajectory.

By the time I applied for a marriage-based green card, I had already experienced the unpredictability of immigration and travel policies. I arrived in the United States on an F1 visa—a sticker in my passport that granted entry for education but was not suitable for maintaining connection with family back home. Although I could legally stay in America for the duration of my PhD program, traveling abroad could jeopardize my student status. If I left the United States, my return depended on whether I could renew my visa at a US consulate overseas. Every year, I planned visits home, but consular closures and other circumstances beyond my control prevented these trips. Ultimately, I was unable to see my family for the first five years of my graduate studies.

Although I never faced the devastating loss and complete inability to return home of the many who migrate due to war or political repression, I experienced, in some small way, what it means to have no control or autonomy. But what I could do was draw clear connections with the stories I found in the archives. I thought about how Soviet-American couples I studied were subjected to strict immigration laws and visa policies. One man missed the birth of his daughter when Soviet officials denied his exit visa due to “poor US-Soviet relations.” In another case, a Soviet woman spent over a decade of married life apart from her American husband because Soviet authorities were convinced that she had access to state secrets.

The Soviet-American couples I studied were subjected to strict immigration laws and visa policies.

To protest their forced separation, these couples created new pathways through the Iron Curtain. If USSR officials refused to deliver mail to the spouses of US citizens, their loved ones found friends who could deliver it. When telephone calls were not put through, they passed messages through US correspondents and foreign officials. While these outward channels helped sustain intimacy, these methods could not provide the level of vulnerability and privacy these relationships relied on to survive. The need to express their love and the pain of separation led some spouses to turn inward, to draft unsent letters, and to produce personal writings.

When husbands and wives did reunite in the United States, some compiled their writings into memoirs and published them abroad. Through memoir, they could turn their feelings into a public record and explore the emotional reality of separation: what it was like not knowing if they would ever see their partner again, or only to hear from their spouse through newspaper articles. In such a publication, Irina McClellan shared that she cried reading her husband’s interview in a smuggled Xerox copy of the New York Times, in which he said that their marriage was “the best thing [he] ever did.”

It would be understandable to interpret these writings as reflections on spousal separation or as “a dialogue of partners fighting together against the communist slavery,” as a Soviet dissident described one such memoir. What stood out to me, however, were the pages dedicated to the family, friends, and the places these immigrants had left behind. They described a subtle yet persistent ache that became palpable to me during my first trip home after five years away.

If I could not bring my family with me, I could at least preserve fragments of memory.

Throughout that visit to my hometown, Birobidzhan, all I could think about while I was with my family was the moment I would have to leave again. I couldn’t bring myself to book a flight back to the United States despite how much I missed my partner. What if this was the last time I saw my family for a long while—or ever? Like Soviet-American spouses in the Cold War era, I resorted to documenting. If I could not bring my family with me, I could at least preserve fragments of memory. I began filming moments of daily life: my childhood friend toasting my stepdad at a New Year’s dinner, my mom swimming at the local pool, my cat sleeping under my parents’ bed.

I was not too different from the people I studied, who used words and old family photographs to keep their loved ones near. As Irina devoted a chapter of her memoir to her granny Sanya, I made a video dedicated to my grandma Nina. Although 21st-century technology means I can call her anytime I want, it is not the same as seeing her nose turn red in the cold of the Russian Far East or taking her to a performance by my childhood dance group. Perhaps for my research subjects, writing about their family offered what this video gave me: a way to create a passage that connects both worlds.

Alisa Kuzmina is a history PhD candidate at the University of Minnesota and a host on the New Books Network (Russian and Eurasian Studies) podcast.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.