In the middle of last summer, seeking an escape from my daily rounds and craving fiction, I picked up Amitav Ghosh’s Sea of Poppies (2008), the first of a still incomplete trilogy of novels set in early 19th-century India, China, and the Indian Ocean. (The second is River of Smoke [2011], and the third has been announced for 2015 publication.) The book had its desired effect almost immediately, transporting me to a small village outside Ghazipur, on the Ganges, where Deeti, a girl with an insubstantial dowry, has been married off to a much older man, an employee in the local opium-processing factory, who turns out to be in the advanced stages of opium addiction. His family compensates for his sexual impotence by intoxicating her with opium on her wedding night and having her impregnated by her husband’s younger brother. I was soon, in my turn, intoxicated: by the lush prose of the novel, the twists and turns of its many interrelated plots, and its compelling descriptions of a world hitherto outside my ken.

As I continued further, I became aware that I was, in the process, learning a great deal of history. The book is set in 1838 during the run-up to the First Opium War between Britain and China (1839-42). The lucrative opium trade with China dominates the agricultural region around Ghazipur; the British sahibs have forced the villagers to use all their land to grow poppies. The quality of the crop, unknown until the petals have fallen and the bare pod can be nicked for sap, determines the annual livelihood of each smallholder. The opium factory at Ghazipur—where the sap is turned into cakes ready for export—flies the British flag, and the boats on its riverfront fly the pennants of the East India Company. The opium trade, Ghosh notes in passing, was an expedient hit upon by the British to rectify their balance of trade with China. While Europeans couldn’t get enough of Chinese tea, silk, and porcelain, the Chinese had little taste for comparable European manufactures; by adding opium to their offerings, British merchants could gain a competitive edge. A second economic project of global scale looms large in the novel: the effort of the British, after abolition, to populate their colonies in the region with coolies, or indentured laborers, from the subcontinent. A refitted slave ship, the Ibis, will, as the novel progresses, gather up many of the characters who figure in Ghosh’s multiple plots and take them from Calcutta into the “Black Water” en route to the island of Mauritius. Among them are Deeti, now widowed, and her lower-caste lover, Kalua, who are fleeing the wrath of Deeti’s in-laws.

.jpg)

A white opium poppy (Papaver somniferum, or sleep-inducing poppy) depicted in a British botanical print of 1853. The petals of Papaver somniferum also come in shades of pink, purple, and red. Credit: Wellcome Library, London. CC-BY 4.0

As I realized all the unfamiliar history that I, as a Europeanist, was effortlessly absorbing by reading Ghosh, I didn’t enjoy the novel any less. But my original escapist impulse was soon supplemented by the professional eye that I turned to the text. Was Ghosh’s history accurate? The exquisitely detailed description of the huge Sudder Opium Factory at Ghazipur, which a terrified Deeti visits for the first and only time when her husband collapses there, rang true; and in fact Ghosh acknowledges his reliance on an 1865 account written by the factory’s one-time superintendent. My consultations with a handful of South Asianist colleagues produced a unanimous opinion that Ghosh’s history could be trusted; this particular novelist, I was told, had both archival and ethnographic training. (I subsequently learned that he holds a PhD in social anthropology from Oxford.) By this point I was persuaded that Sea of Poppies—and its successor, River of Smoke—should form the subject of a Perspectives column. The books deserve to be brought to the attention of AHA members as superlatively good reads and as pedagogical tools for both our students and, quite possibly, given the ascent of global history, ourselves.

Ghosh has availed himself of a vast geographical canvas, one that stretches from India to the Chinese coast, with occasional backward glances at Britain and the trading ports of the eastern United States. His social vision, often compared to that of Dickens, is similarly vast, spanning the full hierarchy from an untouchable like Kalua, to a mulatto sailor from Baltimore, to the orphaned daughter of a poor but genteel French botanist working in India, to the exorbitantly wealthy British merchants stationed in Calcutta and Canton, and the indigenous Indian zamindar elite. He employs a pastiche of literary styles—the thriller, the comedy of manners, the romance—and makes repeated use of coincidence to join together his disparate plots. Artfully constructed fiction is offset by true, historical detail: Ghosh crams in as much of the latter as the plot will bear. Thus the opium factory of Sea of Poppies, a place of manufacture, has its counterpart in River of Smoke inthe similarly thickly described “factories” standing cheek by jowl in the foreign enclave of Canton. These produce no tangible products but instead house the mercantile operations of the various nations permitted to conduct business in China; their name derives from the word “factor,” meaning business intermediary. Who knew that there were two, very different forms of factory critical to the 19th-century global economy?

The world of European imperialism that Ghosh depicts is one of chaotic flux, of a hodgepodge of nationalities, classes, and races, of routine shape-shifting and reinvented identities. In Ghosh’s telling, the chaos is not all bad. Thus in River of Smoke, as the Chinese government seems poised to ban the opium trade, an Indian opium dealer realizes he may be forced to leave China forever; he fears expulsion not only for business reasons, but because “it was here, in Canton, that he had always felt most alive—it was here that he had learnt to live” (p. 324). Such chaos is in many ways uncontainable by a literary text, and so Ghosh “performs” it, allows the reader to participate in it, by his characters’ use of the many argots and slangs in circulation. We hear the nearly unintelligible English of the lascars (non-European sailors on European ships); the touchingly comical franglais of the daughter of the French botanist; the pidgin used by the Chinese to communicate with anglophone traders. No reader will find all these idioms readily decipherable, but everyone will get their gist—and that is, I think, exactly Ghosh’s point. In the world he is describing, everyone has to get by with imperfect understanding. As we grow accustomed to our own imperfect understanding of some of Ghosh’s dialogue, the haze bothers us less, and we begin to wonder how much we really understand when we communicate with speakers of our own native languages, anyway.

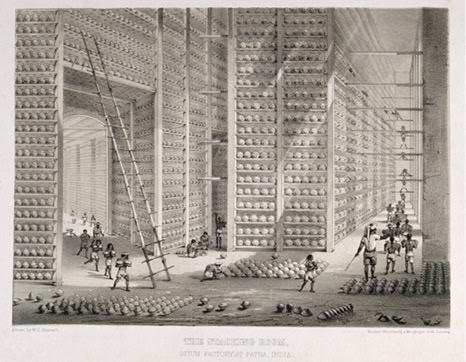

The stacking room of the Patna opium factory, where the finished product was temporarily stored, depicted in a British lithograph of 1850. The Patna and Ghazipur factories, both on the Ganges within easy access of Calcutta, together processed a large portion of the British opium sold in China. Credit: Wellcome Library, London. CC-BY 4.0

How, then, are human relationships forged in a world where all social conventions are in flux? In Sea of Poppies Ghosh meditates on this problem in a philosophical vein. Two riveting scenes show the bodily ministrations—across lines of caste, class, and race—of one adult to another. The first concerns Deeti and Kalua. Walking in the poppy fields at night, Deeti sees Kalua (whom she knows only as her husband’s oxcart driver) set upon by thugs, who beat him into a stupor and allow a horse to defecate on him. Obeying some inarticulable prompting, she puts modesty aside and cleans his body. That moment of intimate caretaking forms the basis of their tie—an enduring love relationship that will blossom only years later. The second such incident concerns two prisoners at the Alipore jail in Calcutta (another institution minutely described by Ghosh), both sentenced to transportation: Neel, a once-powerful zamindar wrongly convicted of forgery; and Ah Fatt, a half-Chinese, half-Indian opium addict convicted of robbery. Neel is made to share a cell with the mute and immobile Ah Fatt, who, in the throes of opium withdrawal, soils himself constantly. The high-caste Neel, who has never taken care of another human being, even his son, finds himself cleaning Ah Fatt. He muses that tender attachment probably arises from “the mere fact of using one’s hands and investing one’s attention in someone other than oneself . . . just as a craftsman’s love for his handiwork is in no way diminished by the fact of its being unreciprocated.” When Ah Fatt speaks for the first time, it is to comfort Neel: “Ah Fatt your friend” (pp. 319, 335). As in the case of Deeti and Kalua, the bond forged by bodily caretaking proves lasting.

In this short space, I’ve been able to give only a sampling of the riches of the first two volumes of the Ghosh trilogy. Either novel could be assigned to good effect in an undergraduate course on world history. In a graduate course on historical method, they could be analyzed in terms of the boundary between history and fiction, between the truths of the archive and those of the imagination. Or they could be enlisted for personal retooling by history professors who want to learn some global history while reading for pleasure.

Amitav Ghosh’s Sea of Poppies (2008) and River of Smoke (2011) are published in the US by Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.