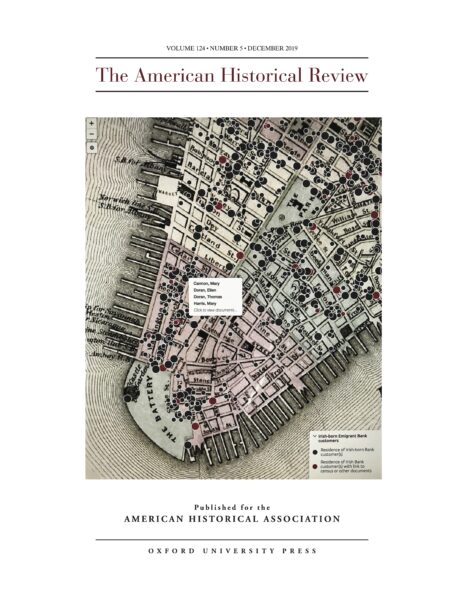

Newspapers, government documents, and even whole manuscript collections are often now available online. Digitization is certainly changing the way historians work, but can it make us better scholars? In “Networks and Opportunities: A Digital History of Ireland’s Great Famine Refugees in New York,” Tyler Anbinder, Cormac Ó Gráda, and Simone A. Wegge present evidence from the records of the Emigrant Savings Bank in New York City to argue that various kinds of networking played a key role in determining whether famine refugees thrived in New York or struggled to scrape by. In the online version of the essay, hyperlinks allow the reader to learn more about the places discussed in the article, scrutinize almost all of the primary sources cited in the notes, and even download the entire database. Pictured here is a detail from the authors’ interactive map, which shows the locations of the homes of the bank’s Irish-born customers in lower Manhattan.

I would be the first to admit that the promise of digital history has, at least in the pages of the American Historical Review, been long deferred. The December issue seeks to redress this by featuring an interactive article based on the analysis of a digital database of more than 15,000 mid-19th-century bank depositors whose assets were held by New York’s Emigrant Savings Bank. In their article, “Networks and Opportunities: A Digital History of Ireland’s Great Famine Refugees in New York,”Tyler Anbinder (George Washington Univ.), Cormac Ó Gráda (Univ. Coll. Dublin), and Simone Wegge (Coll. of Staten Island, CUNY) scour these digitized records to show that even the most wretched of refugees fleeing the Great Irish Famine (1845–49) accumulated surprising savings and made strides up the American socioeconomic ladder. Digitized data rendered in highly localized maps of both Irish parishes and Manhattan wards allow the authors, and readers, to surmise why certain emigrants succeeded. Visualizing emigrant networks—by birthplace, New York residence, employment niche, and the acquisition of resources and skills—reveals the characteristics of successful famine refugees. The authors flesh out the life stories of many of the immigrants found in the database, using census records, ship manifests, and bank ledgers hyperlinked to the electronic version of the article. Part of a larger digital project on famine immigrants, “Moving Beyond ‘From Rags to Riches,’” the electronic version of the article provides access to digitized bank ledgers, interactive maps, and supplementary documents, allowing readers to ask their own questions. For example, with a few clicks, readers can access the bank records of the more than two dozen saloonkeepers in the database, correlating their savings with place of birth, residence, date of emigration, and other data. The overall goal of the digital version of the article, then, is to give students and scholars the ability to do history rather than merely read it.

This innovative digital article is accompanied by some AHR perennials. Every December issue features an “AHR Conversation.” At the suggestion of Steven Conn (Miami Univ., Ohio) and Denise Ho (Yale Univ.), the 2019 Conversation examines the role played by museums and the act of display in the formation of public historical narratives in diverse national contexts. Joined by Ana Lucia Araujo (Howard Univ.), Alice Conklin (Ohio State Univ.), Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett (New York Univ.), and Samuel J. Redman (Univ. of Massachusetts Amherst), the discussion addresses both scholarship on the history of museums and the contested politics of museum display. This comes at a heated moment, as scholars, curators, and states wrestle with problems of provenance, restitution, and the impetus to “decolonize” the imperial museum. Most broadly, the conversation considers some deceptively simple questions: What, exactly, are museums for? Who should the museum “speak”—and answer—to? What responsibility do museum professionals have when it comes to displaying—or smoothing over—a traumatic past? These matters cut to the heart of the underlying role of museums in collecting and organizing items that reflect the power relations embedded in their very acquisition. The conversation will continue with members of the audience at a panel at the AHA annual meeting in New York on Friday, January 3, from 3:30 to 5:00 p.m., with Araujo, Conn, Ho, Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, and Redman in attendance.

The overall goal of the digital version of the article is to give students and scholars the ability to do history rather than merely read it.

Readers intrigued by new developments in museum studies should turn to December’s reviews section, where they’ll find seven museum reviews, including a critical examination of the recently reconfigured Royal Museum for Central Africa in Tervuren, Belgium (which still appears to be haunted by King Leopold’s ghost, despite the efforts to exorcise his coloniality). Other reviews consider the Namibian Independence Museum, Săo Paulo’s immigration museum, an exhibit on “Queer Miami,” the Museum of European and Mediterranean Civilizations in Marseilles, Lisbon’s Museum of Resistance and Freedom, and the Maritime Museum of Denmark.

Another regular AHR feature is the “reappraisal” essay. In the December issue, T. J. Tallie (Univ. of San Diego) revisits a groundbreaking work in African history, Keletso E. Atkins’s oft-cited The Moon Is Dead! Give Us Our Money! The Cultural Origins of an African Work Ethic, Natal, South Africa, 1843–1900 (1993). As Tallie shows, Atkins’s foregrounding of southern African labor regimes as logically consistent, rational, and deserving of full consideration within a proto-capitalist colonial market had a significant impact on scholarship of the African encounter with colonial power, in South Africa and beyond. Tallie also highlights the significance of Atkins’s self-conscious approach as a black scholar writing to and for members of the diaspora.

December also brings two new contributions to our regular “History Unclassified” section. “In Living Color: Early ‘Impressions’ of Slavery and the Limits of Living History,” by Drew Swanson (Wright State Univ.), considers the trajectory of “living history” displays as a problematic mode of public displays of the history of American slavery at sites like Colonial Williamsburg. Swanson considers an earlier wave of living historical representations of slavery to suggest the challenges and hazards of embodied history, as historical attractions used the “authenticity” and “credibility” of formerly enslaved interpreters to advance an apologetic narrative of the slave South. Swanson’s essay is accompanied by Nianshen Song’s (Univ. of Maryland, Baltimore County) piece, “Steps in the Tumen River.” Here Song reflects on his field experiences—as a journalist and then a historian—along the Tumen River, which forms the boundary between China and Korea. His observations trace contending historical memories of the Tumen border from the 17th century to the present. Song’s travels in this fluid region helped him rethink the meaning of state borders from the perspective of locals, trespassers, and the environment, challenging the popular notion that boundaries are naturally formed, static, and always clearly defined.

Because 2019 marks the centenary of the Treaty of Versailles, the December issue devotes some attention to World War I.

Finally, because 2019 marks the centenary of the Treaty of Versailles, the December issue devotes some attention to World War I. Ten scholars reflect in brief essays on the long-term consequences of the treaty’s mandate system, by which the territorial spoils of war were redistributed, dramatically reconfiguring the 20th-century geopolitics of anticolonial self-determination. How did this reshuffling of imperial power configure long-term struggles over minority rights, decolonization, and the shape of nation-states when the colonial era finally came to a close? These essays suggest that from Palestine, to Namibia, to Kurdistan, and beyond, the legacies of the mandatory moment remain pressing questions today. These reflections can be fruitfully read alongside a “review roundtable” focused on director Peter Jackson’s stunning, if controversial, documentary film about the war, They Shall Not Grow Old (2018). While the film applies unprecedented technical wizardry to the visual and audio archives of combat on the Western Front, it does so at the service of a very traditional interpretive scheme, one long surpassed by the historiography in the field. Considerations of the film’s achievements and limits by Santanu Das (Oxford Univ.), Susan R. Grayzel (Utah State Univ.), Jessica Meyer (Univ. of Leeds), and Catherine Robson (New York Univ.) address this paradox from a range of perspectives.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.