On the morning of February 20, 1962, Mrs. Curtis Hamilton served her family a “good, hot breakfast,” just as she did every day. But on this day her family dined al fresco, sipping coffee from thermoses on the dunes of Cocoa Beach, Florida, as they awaited the start of America’s first crewed orbital spaceflight. Her parents, Mr. and Mrs. Joe Hicks, drove in with their granddaughter Debra from Waco, Texas, to join the catered launch party. Meanwhile many more onlookers gazed skyward from the Beach Causeway, which now resembled a parking lot rather than a roadway. At 9:47 am EST, the delighted crowds watched John Glenn accelerate atop an Atlas rocket toward the heavens to orbit the Earth.

The Hamilton-Hicks family was one of millions who, over the past 60 years, vacationed at the liminal localities where Earth and space meet: the facilities of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). While tourism in space is a 21st-century phenomenon, “space tourism” has been a part of American leisure culture since the early days of the Cold War. Following the success of America’s first satellite, Explorer, in 1958, citizens traveled from near and far to witness human space exploration firsthand. Their motivations were manifold: to participate in events recognized as historically significant, to marvel at the technology of space exploration, to educate themselves and their children on the science of spaceflight, to demonstrate their support for the space agency, and to understand how the US government was spending their tax dollars. Regardless of their reasons, visitors were thwarted at the gates of the space centers, which lacked the infrastructure to support large-scale tourism.

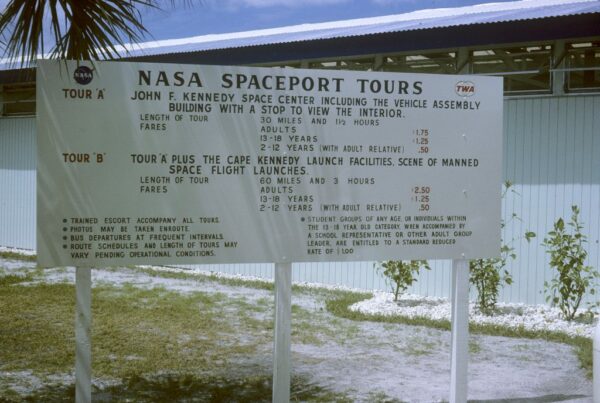

NASA personnel and civic leaders observed the unsolicited visitors with great interest and were keen to co-opt this phenomenon to serve their own agenda. Together, NASA and civic organizations partnered to develop and promote visitor programs and facilities that presented the space agency’s activities without interfering with them. Between 1964 and 1970, space attractions opened at or near the John F. Kennedy Space Center in Brevard County, Florida; the Manned Spacecraft Center (known since 1973 as the Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center) outside of Houston, Texas; and the George C. Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama.

NASA viewed space center tourism as a means to demonstrate to its patrons the value of its programs and, in particular, justify the multi-billion-dollar price tag of Project Apollo. Meanwhile, members of the local chambers of commerce, municipal governments, and business communities saw in space tourism a solution to regional economic and social challenges, from industrial expansion to economic diversification to racial conflict. The ultimate form and function of the space museums and visitor programs reflect the concerns of diverse stakeholders, whose interest in these attractions often had little to do with spaceflight itself.

With the generous support of the American Historical Association and National Aeronautics and Space Administration, I advanced my study of the origins of space tourism in the American South last year. During the tenure of my fellowship, I finished writing two chapters and completed most of the research for my dissertation. In summer 2017 I traveled to Brevard County, Florida, to collect materials related to visitor programs at and around the Kennedy Space Center, which included guided bus tours and an information center, and space-themed community attractions, such as the Astronaut Trail. I worked extensively in the Florida Historical Society’s Library of Florida History and the Brevard County Public Libraries. Through the kindness of current and retired Kennedy Space Center employees, I obtained records from the center’s archives. I also worked in the History Office at NASA Headquarters and the National Archives in College Park, Maryland.

In fall 2017, I traveled to Texas to conduct research on tourism at the Manned Spacecraft Center in Clear Lake and space attractions in the greater Houston area. I worked in the Johnson Space Center History Collection housed at the University of Houston-Clear Lake, the Houston Metropolitan Research Center, the National Archives in Fort Worth, and the papers of Olin E. Teague, chair of the House Subcommittee on Manned Spaceflight, held at the Texas A&M University Cushing Memorial Library and Archives.

In addition to working with traditional archival sources, I conducted oral history interviews to illuminate the experiences of people of less renown—tourists, community actors, and civil servants—integral to the story of space tourism. My research has been enriched through conversations with former tour guides at the Kennedy and Johnson space centers, retired NASA public affairs officers and exhibit designers, business owners, law enforcement personnel, and residents whose lives and careers shaped and were shaped by space tourism.

I am grateful to the AHA and to NASA for supporting my research, and to the archivists, researchers, volunteers, and interviewees for their assistance, enthusiasm, and encouragement.

Applications for the 2018–19 Fellowship in Aerospace History are now open. Winners receive a stipend of $21,250, including travel expenses. Applications are due April 1.

This post first appeared on AHA Today.

Emily Margolis is a doctoral candidate in the Department of History of Science and Technology at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland. Her dissertation, “Space Travel at 1G: Space Tourism in Cold War America,” is a study of the ideas, individuals, and institutions that transformed National Aeronautics and Space Administration facilities into international tourist attractions between 1958 and 1982. She holds a master’s degree in the history of science from the University of Oklahoma and a bachelor’s degree in physics from Princeton University. Emily can be contacted at emily.margolis@jhu.edu.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.