A slogan can be a powerful statement, whether chanted during a protest or used as a campaign’s guiding principle. Over the last 20 years, social movements have created several notable slogans. Anti-globalization activists at the 2001 World Social Forum in Brazil gathered under the slogan “Another World is Possible.” Occupy protesters in 2011 in New York City and beyond declared, “We Are the 99%.” Alicia Garza, Opal Tometi, and Patrisse Cullors launched the “Black Lives Matter” hashtag in 2013 as a painful response to Trayvon Martin’s death. Now, we hear “Defund the Police” in response to the recent vigilante and police killings of Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, George Floyd, and Tony McDade.

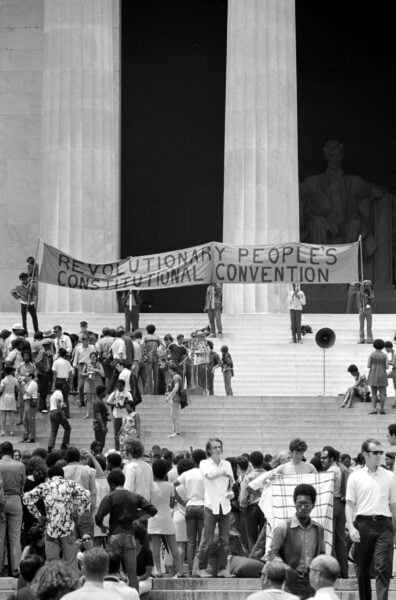

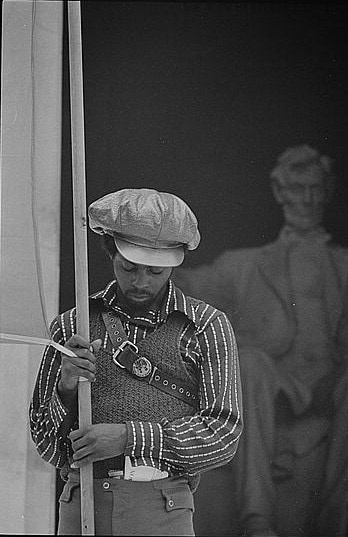

Demonstrators attend a 1970 Black Panther Party Convention at the Lincoln Memorial. Thomas J. O’Halloran and Warren K. Leffler/Library of Congress/Image Cropped.

Compelling political slogans serve many purposes. Chanting slogans binds people together in solidarity while demonstrating in the streets. They can raise questions about and challenge current power arrangements. And, as we have seen with “Defund the Police,” political sayings emanating from the grassroots can spark debate about a movement’s demands, goals, and paths for transformation or reform.

“Defund the Police” has sparked such a debate about the role of law enforcement in the US. The spirit of the refrain arises from decades of activism, scholarship, and community organizing devoted to abolishing police and prisons, as the work of organizations like Critical Resistance and scholars and activists Angela Davis, Ruth Wilson Gilmore, and Mariame Kaba reminds us. But what does the slogan mean?

Many abolitionists, and even policymakers, have taken “Defund the Police” literally. Advocates of this idea claim that more police contact with citizens, especially Black Americans, leads to more arrests, more imprisoned, and more harmed and killed. Consequently, defunding the police is a strategy for reaching a world without police (and prisons). Less radical protesters may support redistributing financial resources from police toward community services without seeking to eliminate policing altogether. Meanwhile, many politicians, including presumptive Democratic Party nominee Joe Biden and Senator Bernie Sanders, have come out against defunding the police. Both have argued that problems in policing can be addressed without starving law enforcement of resources whereas abolitionists claim reforms only improve the criminal justice system’s capabilities of harming more people.

Advocates of “Defund the Police” claim that more police contact with citizens, especially Black Americans, leads to more arrests, more imprisoned, and more harmed and killed.

Of course, this is not the first Black-created protest slogan that has caused such debate. “Black Lives Matter” wasn’t the first either. Current debates around “Defund the Police” reminds me of an even older contested political slogan—Black Power.

On June 16, 1966, police in Greenwood, Mississippi, arrested Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee chairman Stokely Carmichael after a dispute over allowing participants in James Meredith’s March Against Fear to set up a campsite at a local school. After leaving jail, Carmichael declared in an electrifying speech, “What we gonna start sayin’ now is Black Power!” While many ideas associated with Black Power (i.e., racial pride and solidarity, self-determination, cultural integrity) had circulated among activists for decades, Carmichael’s call for Black Power launched a new debate about civil rights, Black politics, and liberation.

In Black Power: The Politics of Liberation (1967), Carmichael and political scientist Charles V. Hamilton advanced a more modest explanation of the term. They stressed the need for Black Americans to reject structural racism, develop racial solidarity, organize around democratic principles, and create their own institutions.

Thomas J. O’Halloran and Warren K. Leffler/Library of Congress/Image Cropped.

Many radical Black Power activists and organizations heeded Carmichael and Hamilton’s calls for the “search for new forms” of Black politics. The Black Panther Party and the League of Revolutionary Workers sought to synthesize Black Power’s nationalist orientation with Marxist-Leninist anti-capitalist politics. Historian Ashley Farmer has illustrated how Black women such as Frances Beale and Gwendolyn Patton used Black Power as a reference point in their critiques of sexism, racism, and imperialism in an effort to express a more feminist vision of liberation.

The response from critics was quick after Carmichael’s speech. Less than a month later, NAACP President Roy Wilkins denounced the slogan, calling it “antiwhite” and suggesting that it “leads to black death.” The goals of Black Power—and the strategies for achieving them—remained too vague for some. Black leftist Robert L. Allen remarked on its limitations, concluding, “revolutionary rhetoric is no substitute for a thorough analysis upon which a program can be constructed.” Martin Luther King Jr. found “Black Power” too militant. However, in an excerpt of his final book published in June 1967 in the New York Times, King argued for Black Americans to cultivate and exercise their collective power as workers, consumers, voters, and political leaders through massive civil disobedience—a clear engagement of Black Power ideas.

A slogan’s power can also make for strange political bedfellows. Conservative expressions of Black Power rested on interpretations of the phrase as calling for Black capitalism, with Black people participating in the market economy as entrepreneurs seeking individual profits. In May 1968, President Richard Nixon mobilized Black Power to discourage Black people from rioting and calling for more social programs. In a radio address mere weeks after King’s assassination, Nixon claimed, “A third bridge is the development of black capitalism. . . . By opening new capital sources, we can help Negroes to start new businesses in the ghetto.” For Nixon, the path toward Black Power lay in owning property, not King’s plans for addressing structural racism and poverty.

Debates about Black Power illustrate how some political slogans are not crafted to appeal to the status quo.

Debates about Black Power illustrate how some political slogans are not crafted to appeal to the status quo. “Black Power” inspired many Black activists in the 1960s to search for a politics outside of liberal reform. However, the ambiguity and tensions within the term allowed civil rights leaders and politicians from both political parties to appropriate, even redefine, elements of Black Power.

Some expressions, such as “Yes We Can,” “Make America Great Again,” and “Medicare for All,” are devised to mobilize broader electoral and political coalitions. But other movements popularize refrains as explicit challenges to existing social and economic relations. And many supporters hope these phrases resist easy co-optation. “Another World is Possible” sought to inspire and challenge people to rethink and struggle for alternatives to global capitalism, the nation-state, militarism and state violence, and environmental degradation. “Black Lives Matter,” a queer Black feminist-inspired statement of the obvious, provoked great consternation among some white Americans who sought to proclaim a colorblindness, but pushed others to reexamine the perilous nature of living and surviving while Black in the United States.

The protests of the killings of Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, George Floyd, Tony McDade, and other Black Americans have introduced a legitimacy crisis in policing among a broader swath of Americans. This crisis of legitimacy has opened a new phase of political struggle and sent pundits, politicians, scholars, and observers across the political spectrum scrambling to define, and redefine, “Defund the Police.” We need to understand the tensions in rhetoric and political debates, but especially the long histories of the politics that inspire these slogans.

Austin McCoy is assistant professor of history at Auburn University. He tweets @AustinMcCoy3.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.