Big handwriting is part of America’s origin story; think of all those upstart signatures on the Declaration of Independence. The phrase “Put your John Hancock here” is an American inside joke, a reminder of revolutionary sass and rebellion against the Crown.

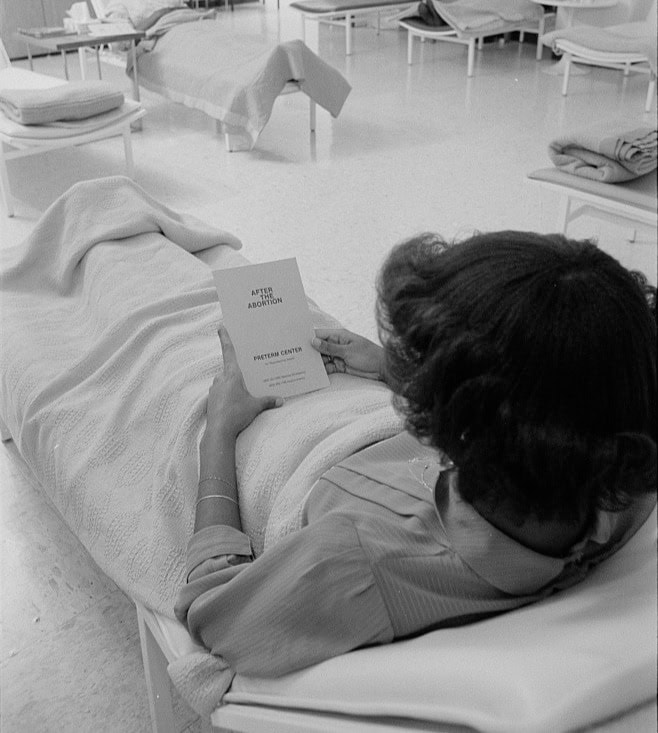

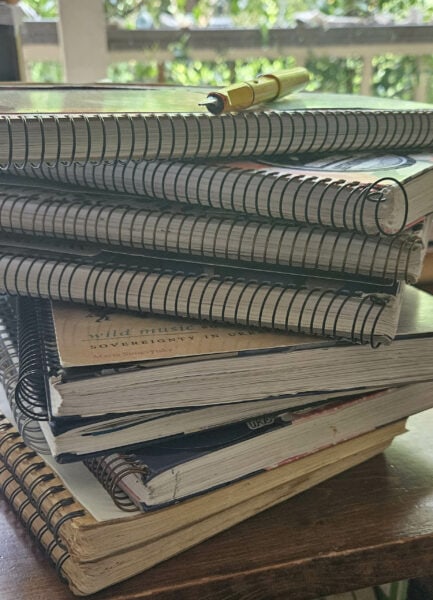

Through 50 years of journaling, Bonnie J. Morris has created an account of the late 20th and early 21st centuries—but who will be able to read her handwriting? Bonnie J. Morris

When I pick up a fountain pen to write about today’s world, I write in a format connecting me to the same founding fathers who did not expect women to make—or record—US history. But writing by hand in my journal, inscribing world events as I personally witnessed and experienced them over the last 50 years, has shaped my approach and identity as a historian.

I filled my first 200-page college-ruled spiral notebook in 1974 at age 12, soon putting aside Bic Banana felt-tips for the more grown-up Sheaffer cartridge fountain pen, which could be obtained at any Peoples Drug where I lived in Bethesda, Maryland. As I recorded notes on historical events of the 1970s, starting with Watergate and Nixon’s resignation speech, I knew that I was no Anne Frank writing under wartime conditions. Nonetheless, I hoped I might contribute useful reflections from the perspective of an adolescent girl, as I watched second-wave feminism emerge and women gaining new rights never before written into American law, from Title IX to Roe v. Wade.

As it turned out, in the 50-year span of my own writing life, I have filled more than 200 journal volumes and followed astounding shifts in sex roles, sexuality, gender, race, and power. I came of age with radical feminism, the LGBTQ+ rights movement, the so-close-to-being-ratified Equal Rights Amendment, Black Americans winning greater roles in public office, and the development of women’s history as a field of scholarship. As these cultural changes continue to be revisited and interrogated in public life and academia, my journals map out a halcyon era for the women’s communities and activism I joined. The entries recorded in Sheaffer ink speak to coming out as a teenager, my college and graduate school years pursuing women’s history, becoming an archivist of the women’s music movement, and writing lesbian history texts with all the joys and implied responsibility of documenting a still-marginalized population I belonged to myself. Reaching for an old notebook today, I can use my eyewitness notes as a primary source on protest marches, feminist speeches, bar nights, academic conferences, election cycles, abortion rights rallies, the events of 9/11, and collective planning efforts to get women’s history into museums.

The keystroke and email correspondence have mostly replaced the pen in hand.

But this entire record is written in cursive, a format for communication that today feels almost as obscure as the tin-can telephone. What I thought would be a record for the ages has become less accessible to future generations than I had hoped.

My naive assumption that I had done all I could to inform future generations changed in October 2023, when I visited the June L. Mazer Lesbian Archives in West Hollywood.

After a tour of rooms filled with other women’s handwritten journals and letters, our guide raised the problem of finding interns capable of helping interpret such collections. Today’s college students were excited to encounter California’s LGBTQ+ past and signed up for archival work hoping to study their own heritage. But many donated artifacts were in cursive writing, the signature scrawl of other women who once dared to keep a preinternet record of their lives. And today, far fewer interns are adept at reading cursive, the medium of a time long past.

For those born after the mid-1990s, the keystroke and email correspondence have mostly replaced the pen in hand, and the distance from handwriting increased when various US states phased out instruction in cursive writing. Cursive survives mainly as a signature on the dotted line, and even that can be generated by a computer. Women’s personal journals today more often take the form of online blogs or social media feeds. I was aghast to realize the scope of change, and what it meant for my work as a well-meaning diarist of the late 20th century. Who will be able to interpret my inked journals when I’m gone? But the visit to the Mazer also forced me to reconsider my work as an instructor of present-day history students. How might I express to them the blessing and curse of cursive and its powerful place in America’s written past?

I soon found the question of cursive handwriting raised in other public conversations and in local education initiatives. Assemblywoman Sharon Quirk-Silva introduced California bill AB 446, requiring that cursive be taught from first to sixth grade beginning in 2024. The law, signed into law by Governor Gavin Newsom in October 2023, generated a flood of mixed opinions. Responses across social media ranged from “When was it taken off state standards?” to “My own kids don’t know it; it’s like a secret language now” to “Face it: today, your fingerprint is your signature.”

In Education Week, Elizabeth Heubeck laid out the facts and figures of this debate in the article “More States Require Schools to Teach Cursive Writing. Why?” US schools began teaching cursive as early as 1850, but by 2010, new Common Core State Standards favored “keyboarding skills.” Heubeck explored the great contradictions of our era, in which some teachers see handwritten exams as a way around AI plagiarism, though elsewhere AI is a new tool for translating ancient script. At the same time, John Woolfolk pondered the timing of AB 446 in the Santa Cruz Sentinel. In an era burdened by so many other education controversies, he wrote, is cursive handwriting instruction a waste of class time, or a necessary equalizer, giving all students the ability to read historical documents? At the end of the day, fluidity in reading cursive material might be an asset for the next generation of historians, but being able to write it is less urgent.

Writing, after all, is a motor skill, one that does not come naturally to everyone. In past classrooms, difficulty in mastering the formal swoops and loops of cursive uppercase shamed the otherwise bright students who scored poor grades in penmanship. The computer keyboard thankfully leveled the playing field for disabled, injured, and neurodivergent students, and ADA directives assist disabled students to complete high school and college assignments on a laptop. Thus, typed print has amplified and diversified academic, political, and artistic voices, a progression I see and celebrate in my own classrooms.

Their two hands observe, record, and critique US history with the same energy as my younger fountain pen.

I watched that gradual change from the scrawled intimacy of old-style written responses during the 20 years I worked as a reader scoring Advanced Placement US history exams. From 2001 to 2021, anyone hired for AP scoring sessions navigated bracing waves of cursive, most of us challenged to comprehend over a thousand handwritten essays during one week each June. But during the COVID-19 crisis in 2020, the Educational Testing Service moved to touchless online scoring, with students uploading typed essays. This has been easier on everyone, without any loss to the intended goal of measuring historical analysis and comprehension.

In my history classes at the University of California, Berkeley, I plan to phase out timed in-class exams requiring students to write long essays in a bluebook with a pen. Undergraduates explained that no one else had asked them to dash off a humanities essay by hand since ninth grade. And what takes me mere minutes to decipher and grade equals hours of translation work for my graduate assistants, who are less cozy with wide-ranging handwriting styles. These generational differences lead me to conclude that I am unreasonably penalizing students who would otherwise perform well on a typed test. Their mind-hand connection for rapid response has simply been trained differently over time. Though I may be at my happiest and most expository while my fountain pen nib flies over a blank page, that medium is hardly the preferred format used today by my own students. Their creativity lives on glass, the vertical computer screen a writing tablet filled by two hands on plastic keys—or, even more likely, their work is tapped out directly on a phone screen. Their two hands observe, record, and critique US history with the same energy as my younger fountain pen.

Still, I would argue that there are plenty of ways and reasons to keep cursive in the classroom. The feel of an old-fashioned pen in my hand did connect me, in my own school days, to the inkwell-strewn American past and the struggles of our diverse ancestors to claim literacy as a right. As tensions flare over how best to teach the history of slavery, women’s rights, and immigration, the ability to interpret handwriting is a gateway to reading past documents on who counts as an American: the slave-ownership and manumission documents, naturalization papers, and birth certificates of our family histories. When students—ideally, along with their parents—watch the Henry Louis Gates Jr. series Finding Your Roots on PBS, viewers’ eyes are directed to the looping handwriting of America’s past slave auction posters, ship manifests, wartime musters. Often, such lush cursive documents draw the eye, only to reveal heart-wrenching content.

As archaeologists and paleographers have made meaning out of Egyptian hieroglyphics and Dead Sea Scrolls, as those students studying the 15th or 17th or 19th century must learn to read the handwriting of those periods, students looking back at the 20th century will have to learn to read cursive. Today, dedicated students may catch a sense of excitement in mastering cursive for historical purposes. Handwriting may be less and less a function for daily use in the 21st century and beyond. But bringing confident deciphering skills to the treasure hunt of history has its rewards when “old writing” shares the past with us.

Bonnie J. Morris is a lecturer in women’s history at the University of California, Berkeley, and the author of 19 books, most recently What’s the Score? 25 Years of Teaching Women’s Sports History.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.