The Vietnam War and the stories that surround it have been controversial from nearly the moment American servicemen and women set foot in Vietnam. It is perhaps unsurprising that any move to commemorate the war has spawned protest, but the divisiveness engendered by the controversy points to a larger debate in the interpretation of the history of war in America. In 2008, the Department of Defense was authorized by Congress to “conduct a program to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the Vietnam War.” As part of these efforts, the Department of Defense created a website announcing the commemoration and highlighting events around the country. But the website has also drawn criticism from some veterans groups and historians, who worry that the commemoration efforts in general and the website in particular constitute an effort to take control of the narrative of the war and whitewash its history.

The controversy hinges on the idea of commemoration, which to critics of the war implies praise, validation, and legitimation of the military actions in Vietnam. The explicit purposes of the commemoration authorized by Congress were “to thank and honor veterans of the Vietnam War . . . for their service and sacrifice,” “to highlight the advances in technology, science, and medicine related to military research,” and to recognize contributions and sacrifices on the home front and by US allies.1 According to the Vietnam Peace Commemoration Committee, the programs designed by the Department of Defense do not provide an “opportunity to hear, recognize and perhaps reconcile or heal the lasting wounds of that era.”2 Rather, as Marilyn Young, renowned historian of the Vietnam era and an organizing member of the Vietnam Peace Commemoration Committee, expressed it in a phone interview, “The Pentagon is trying to make a bad war good. It not only can’t be done, but it shouldn’t be done.”

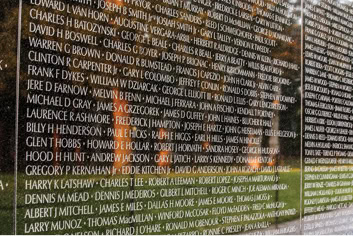

Jeff Kubina, CC BY-SA 2.0, bit.ly/1pqm9aS

Richard Ricciardi, CC By-NC 2.0, bit.ly/1wzI93O

Flickr user eqkrishena, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0, https://bit.ly/1AqEQQc

In the United States, remembering the Vietnam War is a fraught process. The first memorial to be installed on the National Mall in Washington, DC, the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, was dedicated in 1982. Some veterans found the wall too abstract, so the Three Servicemen Statue was commissioned; it was completed in 1984. In 1993, more than a decade after the first memorial opened, the Vietnam Women’s Memorial was dedicated on the mall.

One of the most controversial features of the website is an interactive time line.3 Visitors to the site can flip through the pages of the time line, which is set up like a book, to find out what was going on in the conflict during specific years. The entries are often perfunctory and do not link to more information, and the events selected (and excluded) have drawn some criticism. In some ways, the selection of events that are included on the time line reflects the limited scope of the congressional authorization—not to tell the definitive story of the Vietnam War, but to tell the story of military operations, with a specific focus on the sacrifices of Americans and their allies and the technological and medical advances born of war. Yet the criticisms of the time line also reflect the broader difficulty of trying to tell a divisive story without a broad and inclusive context.

For example, in addition to military actions in Vietnam and selected events in the domestic United States, the time line includes an entry for every Medal of Honor awarded during the conflict, the highest award given to military personnel. On the one hand, including Medal of Honor recipients fulfills the directive to “thank and honor the veterans.” On the other hand, as Mark Boulton, author of Failing Our Veterans: The G.I. Bill and the Vietnam Generation (NYU Press, 2014), points out in an e-mail, “those stories might have more impact as a separate section which highlights heroism rather than being interspersed throughout the narrative time line.” Further, the category of Medal of Honor recipient is not as objective as it might first appear. The condition that it be awarded for action during engagement with the enemy precludes the eligibility of many categories of service personnel, including all women, and narrows the story of military service that it can tell. Such categorizations, observes Kara Dixon Vuic, author of Officer, Nurse, Woman: The Army Nurse Corps in the Vietnam War (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2010), reproduce the idea that “woman” was synonymous with “nurse” during the conflict and prevent a larger engagement with the history of women and of gender in the US military. In point of fact, 25 to 30 percent of nurses during the height of the conflict were men. Further, while they were engaged in cutting-edge medical procedures and humanitarian work, nurses also encountered other less savory parts of the conflict—treating adult Vietnamese patients (both allied and enemy), caring for victims of vehicle crashes and venereal disease, and helping to run the free drug-treatment program provided by the army. While the website notes that the Vietnam War did see an opening of the ranks for women, it has “no discussion of women pushing for this for decades,” Vuic said in an interview. The emphasis on valor obscures a broader investigation of military service.

People on both sides of the debate—the authors of the Department of Defense website and those who are protesting it—show signs of being willing to listen to each other. An early draft of the time line characterized the unprovoked murder of Vietnamese civilians by American soldiers at My Lai as an “incident.” The time line has since been amended to say that a division of American troops “killed hundreds of Vietnamese citizens,” though the word “massacre” still does not appear. Dialogues on polarizing issues relating to the Vietnam War will continue next year. A wide spectrum of views on these issues will be represented at an upcoming conference on the history and legacy of the war, cosponsored by New York University and by the Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies at the University of Notre Dame. The conference will be held at NYU’s Washington, DC, campus on April 30 and May 1, 2015.

The controversy over the Department of Defense website is a microcosm of a larger debate: how to tell the story of the US military within a broader history of the United States and its role in the world. Official histories have been written by the US military since the American Civil War, and the historian’s role in the US military was codified further during World War II. This type of focused history, written by the armed forces for the armed forces, is vital, says William Hammond, the former chief of the General Histories Branch of the Center of Military History and author of Reporting Vietnam: Media and the Military at War (University Press of Kansas, 1998). “The army learns from its history,” Hammond said in a phone interview. “It has no memory without its historians.” It is of note that the Department of Defense website has an odd relationship to this tradition of institutional history. The website does not aim to present a definitive history of the Vietnam War, or even an official one. Yet many historians, including those protesting the website, would argue that the history of the US military cannot be told in isolation. As Mark Boulton observes, the website might be construed as “a limited effort to focus on combat engagements, acts of valor, and societal advances made as a result of the war, but the complexity and divisiveness of the Vietnam era is not represented.” Further, Boulton writes that the lack of “political and cultural context” prevents us from grappling with “some vitally important historical lessons to come out of the Vietnam era, such as the role of protest movements or the brutalizing nature of modern warfare on victims and participants.” In other words, telling the history of the Vietnam War may not be possible without telling the history of the Vietnam era.

The Vietnam War Commemoration website seems to be a locus of irresolvable conflict between those who believe a narrow military history of the conflict is possible and those who insist on the need for broader context. According to the Standards for Museum Exhibits Dealing with Historical Subjects adopted more than a decade ago by the AHA Council, along with the governing bodies of the Organization of American Historians, the Society for History in the Federal Government, and the National Council on Public History, a controversial exhibit should adhere to this point: “The public should be able to see that history is a changing process of interpretation and reinterpretation formed through gathering and reviewing evidence, drawing conclusions, and presenting the conclusions in text or exhibit format.” The controversy around the website reminds us that this process of interpretation and reinterpretation is often quite contested.

Emily Swafford is the AHA’s programs manager.

- The United States of America: Vietnam War Commemoration, “Commemoration Objectives: In Accordance with Public Law 110-181 SEC.598,” https://www.vietnamwar50th.com/about/Commemoration_Objectives/. [↩]

- “Signers of the Letter from the Vietnam Peace Commemoration Committee,” Viet Nam Today, October 2, 2014, https://borderconflict.blogspot.com/2014/10/signers-of-letter-from-vietnam-peace.html. [↩]

- The United States of America: Vietnam War Commemoration, “Interactive Timeline,” https://www.vietnamwar50th.com/timeline/. [↩]

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.