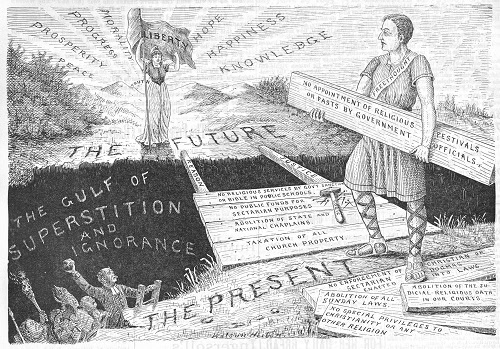

The cartoonist Watson Heston represented freethinkers as young white men in his drawings. This image was published in the June 1895 issue of the Truth Seeker, a freethought journal.

In the 1920s, the small town came in for ruthless ridicule from the likes of Sinclair Lewis and H. L. Mencken. The “village atheist,” invented by author Van Wyck Brooks, became one of the stock characters that populated imagined American hamlets of the late 19th century—the token unbeliever, raving to the wind in a vast landscape of mindless, pointless piety, the exception that proved the rule of benighted ignorance. At the same time, Christian fundamentalism’s star rose, acquiring notoriety and influence through the 1925 trial of John Scopes. The nation’s atheists responded with flashy, media-friendly legal campaigns of their own, to fight for their civil liberties and challenge church-state connections. These tendencies consigned to nostalgia whatever culture of irreligion had in fact existed before the turn of the century.

The historian of religion Leigh Eric Schmidt (Washington Univ. in St. Louis) takes a step toward piecing together this culture in his new book, Village Atheists: How America’s Unbelievers Made Their Way in a Godly Nation (Princeton Univ. Press). In the late 19th century, Schmidt has found, hostility to atheists was all too real: by law, they couldn’t serve on juries or testify in court, they could be arrested for distributing printed materials, and many faced harassment or violence from neighbors. Isolation often produced dissemblance about their true convictions. But if they had lived in one community for years, they might be considered more or less upright citizens: eccentric but dependable in a pinch. Simultaneously, overlapping groups of freethinkers, secularists, and “liberals” (all of whom professed no religion) commanded large audiences on the lecture circuit, published nationally circulated journals, and formed strong networks. Some were popular speakers, like Emma Goldman and Robert Ingersoll, drawing large crowds of atheists and curious believers alike. But Schmidt focuses on four figures who are all but forgotten today, reconstructing a culture of unbelief that permeated small-town life, on that culture’s own terms.

Village Atheists grew from Schmidt’s work on post-Protestantism—the various postbellum spiritual movements away from mainline denominations—in Restless Souls: The Making of American Spirituality (2005). Unitarians, spiritualists, Congregationalists-turned-Buddhists, and other “seekers” “started off in a Protestant world and became unmoored from it in one way or another,” he says. “I saw them as religious liberals and cosmopolitans. And then I saw these atheists and freethinkers as secular cousins of those religious liberals—the ones who, instead of becoming spiritualists or going into New Thought, became diehard critics of that Protestant world.”

For example, C. B. Reynolds, one of the subjects of the four case studies in Village Atheists, imported the tent revival from his experience as a fervent preacher among the Seventh-day Adventists, a group preparing for the return of the Lord, in part by observing the Sabbath on Saturday instead of Sunday. “To be a village Adventist, like being a village atheist, was to be a very distinct minority,” Schmidt writes. “Habituated to attacking conventional Protestant Sabbatarianism . . . Reynolds found it easy enough to recycle Adventist exegesis for secularist purposes.”

Unfurling his tent everywhere he went, even after becoming a freethinker in the 1880s, he attracted onlookers accustomed to attending revivals. “No other means will so quickly develop backbone in the mollusks,” Reynolds declared about potential “converts” in 1885. “When they see every afternoon and evening immense crowds flocking to the tent, they will so rapidly gain vertebrae that they will declare they were always heart and soul in the good work.” The Adventists’ early embrace of the cause of church-state separation also schooled Reynolds well in his movement toward freethinking. He went back and forth between belief and unbelief, demonstrating the flexibility of late 19th-century religious experience in the United States. In one town, Baptists lent him their church to perform a secular funeral for a child.

But toleration was often the exception, not the rule. In 1887, Reynolds was tried for blasphemy, still a legal offense. That same year, Anthony Comstock’s Society for the Suppression of Vice tipped off US marshals about Elmina Slenker, a Virginia atheist known for distributing “obscene” materials related to marriage, the body, and sexuality in the mail. “To those going after her,” writes Schmidt, “her blasphemy and obscenity were utterly entangled; her shameful irreligion and her ‘immoral sentiments’ about sex were all part of the same witch’s brew.” Hauled into court, where she naturally refused to take an oath, Slenker epitomized the sort of freethinker who riled other atheists by proclaiming her right to trespass obscenity laws—going so far as to use vulgar terms like fuckin her writings. Respectability was important to many atheists, as they often faced charges of libertinism. One activist worried, “Who does not know that such a charge [of obscenity] is an ‘entering wedge’ . . . to get works of Free Thought excluded from the public eye?” Schmidt argues that Slenker’s case signified a prosecutorial turn away from blasphemy to obscenity, which “would bedevil the lives of a significant cadre of freethinkers and infidels and raise new doubts about the equal protection of their civil liberties.”

The world of the late 19th century, then, was more malleable when it came to belief and unbelief than stereotypes of churchgoing Victorians would let on. It’s a far cry from today’s New Atheists—led by the media-friendly likes of Bill Maher, Sam Harris, Richard Dawkins, and the late Christopher Hitchens—who usually proclaim the bedrock supremacy of science while castigating all religion as superstitious nonsense that actively damages public life. While the number of self-identified atheists in the United States is small, it’s growing, likely enhanced by the prominence of these figures and their willingness to combat challengers colorfully. Still, the New Atheism’s militancy—for example, around the supposed relationship between Islam and terrorism—has stirred controversy.

Schmidt, who’s taught a course on secularism, nonbelief, and atheism three times (at Washington University and Harvard Divinity School), says his students influenced his thinking, particularly those committed to New Atheism. “I often will attract a student or two who are quite committed to the atheist, secularist worldview,” he says. “I try to get them to look at the world through the other perspective as well, because what I find among the New Atheists is that they’re starving the middle ground of oxygen. I want my students to be able to see that it’s good to let some air flow here, and to be able to move back and forth in that kind of dialogic way with religious people.” Raised in the progressive United Methodist Church, Schmidt still approaches primary sources wearing the “spectacles” of Social Gospel Protestantism. “Probably the reason I’m so concerned to engage the New Atheists in that particular conversation is because I actually care a lot about the middle ground perspective, and I want to see that ecumenical Protestant perspective still have a presence in American public life.” Nonetheless, he describes himself as “a practicing scholar, not a practicing believer or unbeliever,” when he researches and writes.

The 19th century’s “old atheism,” for want of a better term, doesn’t make for an unblemished ancestor for today’s godless students. Village Atheists discusses the divisions in the movement over gender and race in particular. Missouri cartoonist Watson Heston, cast from the Thomas Nast mold, drew allegories of reason triumphing over superstition, with the former represented as a young white man. For atheists like Heston, women were figures of piety and therefore not trustworthy freethinkers. “A lot of this, especially from the admirers of Heston, is an embodiment of this masculinist bravado that the male freethinkers are drawn to,” Schmidt says. “They’re always setting that up in contrast to the sentimentality of women, the piety of women. So it can be very aggressive and even hostile in the way they think about the divide between men and women.” Race divided the movement regionally. Heston had “no interest in solidarity with Frederick Douglass,” Schmidt says, but in figures popular in the Midwest and Northeast, “you see some solidarity.” Very few small-town African American atheists emerged in his research, though some would gain national renown during and after the Great Migration, when black enclaves grew in cities.

Schmidt plans to dig deeper into the social and community life of atheists in forthcoming work, including their attempts to establish freethinking and humanist communities, their “ritual life,” and their participation in civil liberties movements. His deep reading in letters from small-town citizens to the editors of infidel journals—a major source of the anecdotes in Village Atheists—prove that irreligion existed in all areas of the country, including what would become the Bible Belt. The challenge now is to flesh out that world in more detail, perhaps to provide a way for scholars to understand that the associational life Tocqueville observed did not comprise only the religious.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.