Editor’s Note: This is the second installment in a two-part column. The first column is available here.

Alone in the archives, we sometimes encounter people on the worst days of their lives—while standing trial, being separated from family members, or experiencing violence. Meditating over the smallest details, we absorb story after story. These stories follow us home as we translate others’ experiences for readers. Empathy is a core tool of the historical discipline, but it can come at a cost, one that—too often—is not openly discussed.

Incorporating trauma-informed pedagogy into graduate education can prepare students for what they might encounter as their careers and research progress. Axville/Unsplash

This repeated and regular exposure to traumatic events can cause vicarious trauma, whose symptoms—intrusive thoughts, anger or depression, a heighted state of alertness, difficulty concentrating, and trouble sleeping—are similar to those of post-traumatic stress disorder. Left unaddressed, vicarious trauma can trigger physical or mental health crises and burnout.

Increasingly, we have begun to recognize how vicarious trauma can affect those in helping professions, such as emergency responders, social workers, and counselors. While “historian” might not be the first profession that jumps to mind when thinking of trauma exposure, the historian’s empathetic engagement with traumatic events, the solitary nature of the research and writing process, and an often-unhealthy work/life balance can create a perfect storm for vicarious traumatization. The risk of vicarious trauma increases for individuals who have experienced traumatic events in their own lives. If we want to cultivate an inclusive discipline that empowers historians from all backgrounds, we need to address this issue head on.

Adopting a trauma-informed approach within graduate education could help mitigate the effects of trauma exposure among early career historians. In addition to teaching students about theory, research methodology, and the hidden curriculum of academia, history graduate seminars can train students to navigate this potential pitfall by naming and explaining the nature of vicarious trauma, connecting students to a scholarly community, and encouraging strategies for self-care.

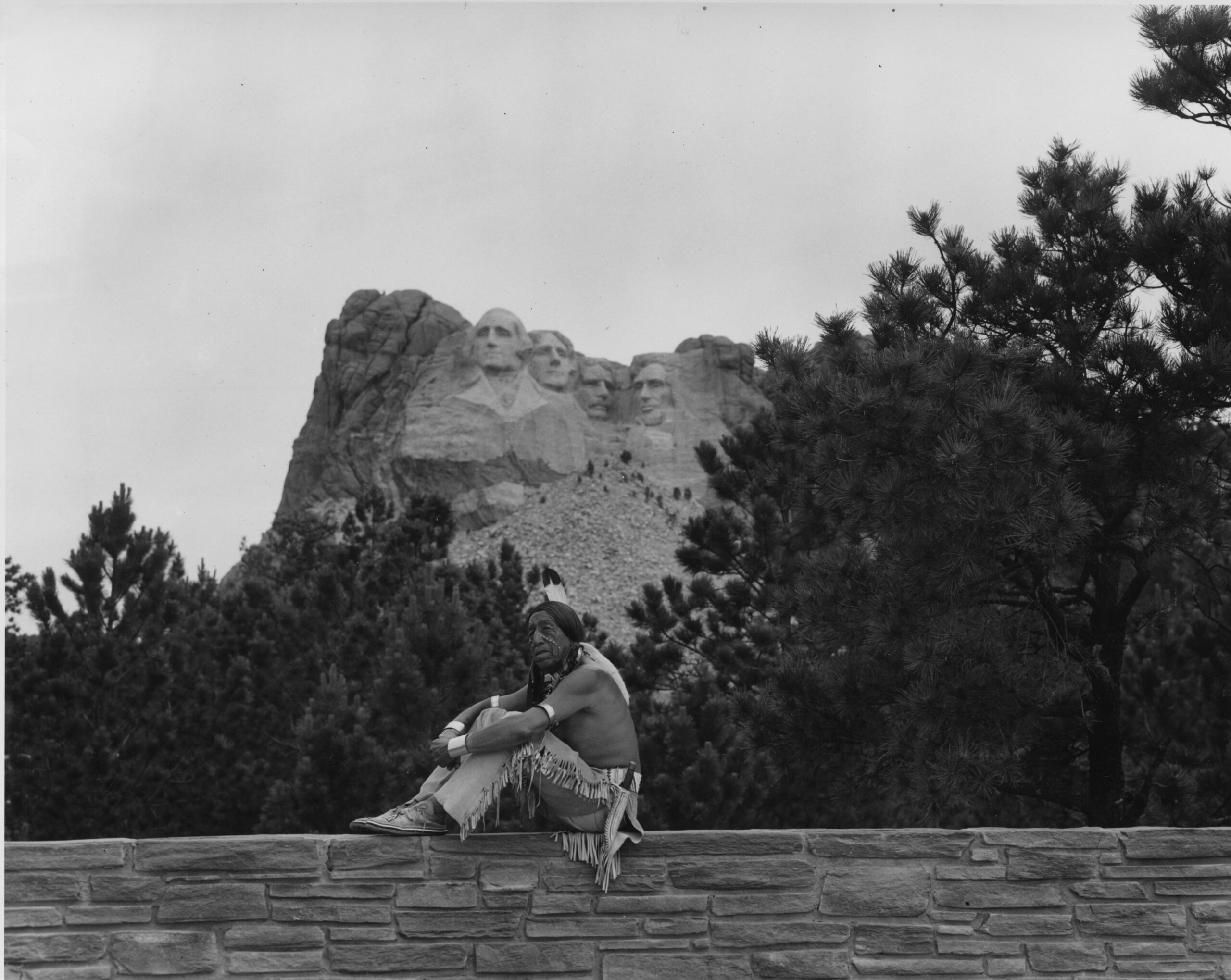

For many people, identifying vicarious trauma can be challenging.

Explaining the nature of vicarious trauma and how it can affect historians is the first and most important step. I spoke with Jen Luettel Schweer, a counselor and director of Georgetown University’s Sexual Assault Response and Prevention Services, about it. For many people, identifying vicarious trauma can be challenging, Luettel Schweer explained: “Vicarious trauma can become something that’s playing in the background of your brain all the time . . . . It’s like white noise.” That is why it is so important to educate students about what vicarious trauma is, what it can look like, and how to address it. Even providing a term to describe this type of trauma matters, Luettel Schweer noted, adding, “Naming is really powerful because naming it normalizes it.”

Introducing this concept early in a historian’s career is particularly beneficial. It may mean the difference between someone identifying what they are experiencing and seeking help versus leaving the discipline altogether, mistakenly thinking they are not cut out for the work.

Faculty members need not be experts to include a discussion of vicarious trauma in their graduate courses. Since most universities have access to trained mental health professionals, this is an excellent opportunity to bring an outside expert into class to discuss vicarious trauma, ways to recognize it, and how to mitigate it. This approach has the added benefit of exposing graduate students to campus resources early in their careers, which those pursuing a PhD may benefit from for years to come.

Graduate programs also can equip students by helping them to build a strong professional community during their coursework. The solitary nature of historical research can exacerbate the effects of regular trauma exposure. The graduate seminar offers an important starting point for connecting students with each other. There is power in community, and having a network of peers with whom one can commiserate is an important tool for combating the isolation of much historical work.

The graduate seminar offers an important starting point for connecting students with each other.

But one’s cohort may not be enough, and graduate programs can help connect new graduate students with peers and scholars from outside their cohort. Katie Benton-Cohen, a professor of history at Georgetown, does this in her research methods seminar by inviting later-stage graduate students and their mentors to speak about their experiences. In addition to representing a range of research areas, these guests come from a variety of backgrounds, including international students, first-generation college graduates, parents, those who had long careers before entering academia, and those who entered graduate school straight from undergrad. Benton-Cohen’s goal is to demonstrate that there is not a single way to move through graduate school or to be a historian. These conversations also help create connections across cohorts and fields, expanding each student’s scholarly community and further reducing the sense of isolation that can occur.

Lastly, graduate programs—just as they train students in theory and methodology—can equip students with strategies for caring for themselves as a whole person, an essential tool for preventing and minimizing vicarious trauma. These may include creating a clear separation between work and the rest of one’s life, establishing routines to decompress, minimizing potentially triggering material outside of work, having fulfilling personal relationships, being part of a community, getting enough sleep, spending time in nature, and taking care of one’s body, mind, and spirit. These are strategies recommended to new therapists, who encounter regular trauma through their work, and they should be part of historians’ toolkits as well. Graduate classrooms offer a valuable space for students and faculty to discuss what it could look like to incorporate these strategies into the rhythms of their work.

While there may be a temptation to roll one’s eyes at the idea of “self-care,” this term is not about expensive spa treatments or TikTok trends. It is about putting on our own oxygen masks so that we can continue this difficult but crucial work in the long term. As feminist scholar Audre Lorde declared in her essay, “A Burst of Light,” “Caring for myself is not self-indulgence, it is self-preservation, and that is an act of political warfare.”

If we want to train a new generation of historians who have the resilience to carry out this essential work, we must both acknowledge the potential for vicarious trauma and equip them with the strategies they need to move beyond it.

The author thanks Jen Luettel Schweer and Katie Benton-Cohen for sharing their time and expertise.

Erica Lally is a PhD candidate at Georgetown University, where her research focuses on citizenship, surveillance, and state development in the early 20th-century United States.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.