The 19th Amendment’s centennial in 2020 fueled an exuberant surge of new research and collaborative public history projects around the topic of women’s suffrage. This renewed interest in women’s history was invigorating for those of us who had long engaged in such research and were happy to share our findings with a curious public. Scholarly collaborations with government agencies such as the National Park Service (NPS) were especially exciting opportunities to engage with a wider audience.

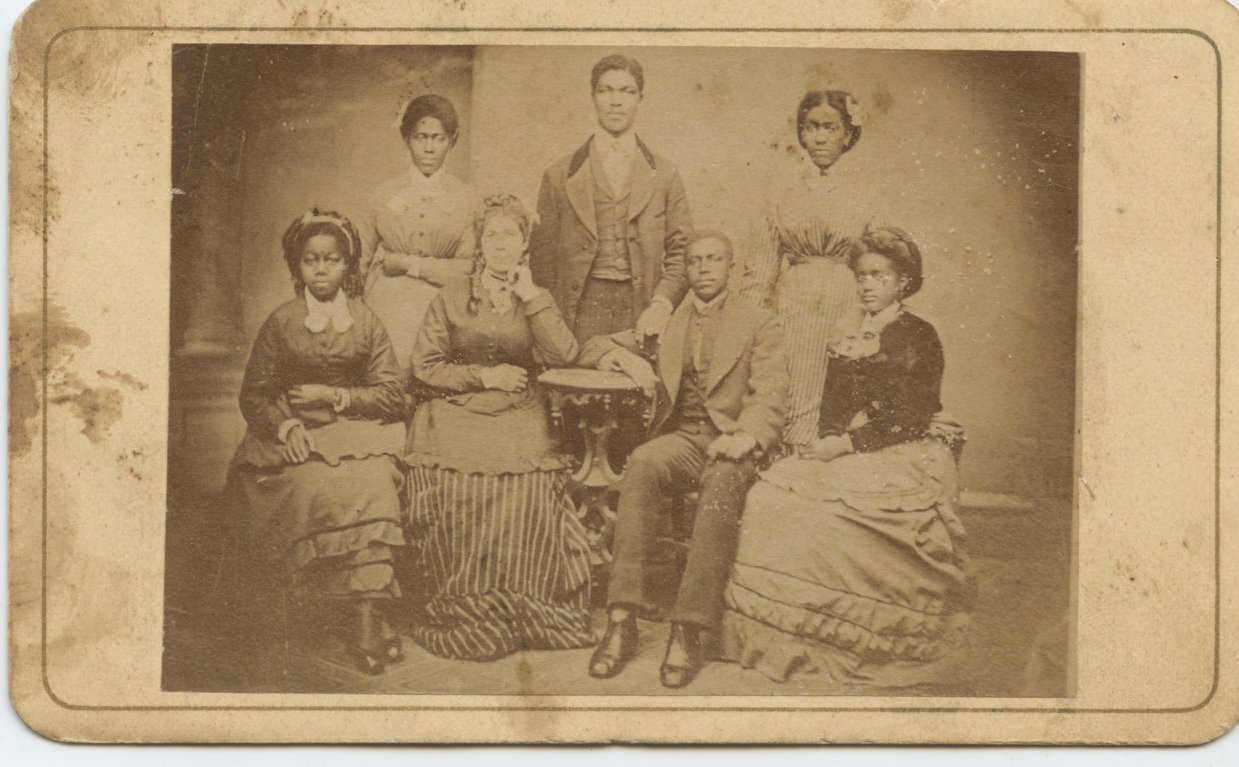

Suffragist Annie Tinker and unknown woman. Tinker, or “Dan” as she preferred to be called, transgressed the norms of her era by wearing masculine clothing and engaging in intimate relationships with other women. Courtesy Incorporated Village of Port Jefferson Digital Archives, Port Jefferson, New York

At the request of the congressionally established Women’s Suffrage Centennial Commission (WSCC), I wrote an article titled “The Very Queer History of the Suffrage Movement.” Rooted in my most recent book, this article focused on the lives of suffragists who defied the gender and sexual norms of their generation. I highlighted those who queered the norm through their gender expression, such as Annie Tinker who dressed in “mannish” clothing and paraded triumphantly through the streets with a suffragist cavalry on horseback during suffrage parades. The article also featured the stories of suffragists in long-term same-sex relationships, such as Gail Laughlin and Dr. Mary Sperry, who cared for each other in life and death. Although modern terms like lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, or nonbinary were not in popular usage or had not yet been created in the era before the 1920s, these suffragists through their same-sex relationships, transness, and gender nonconformity might identify today as part of the LGBTQ+ community. In late 2020, the NPS requested permission, which I granted, to republish the WSCC article on its website as part of its larger project to highlight the research of suffrage scholars.

Since Donald Trump’s second inauguration as president in January 2025, the federal government has declared war on what it refers to as “woke gender ideology.” On his first day in office, Trump issued executive orders to eliminate “gender ideology extremism” and end diversity, equity, and inclusion programs. To comply with the new federal policies, in February officials began to purge all references to transgender and queer people from NPS websites and replace the acronym LGBTQ+ (for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, plus) with LGB. My 2020 article on the NPS website was edited to remove the words transgender, nonbinary, genderfluid, and butch. The intent of these actions was clear: to erase transgender and genderqueer people from the historical record.

This erasure has a long history. Suffrage leaders themselves, concerned with countering antisuffrage criticism, obscured the queerness of the movement by promoting a public image of suffragists as womanly women and respectable wives and mothers. In uplifting an image of ideal femininity and heteronormative respectability, suffrage organizations marginalized gender nonconforming and nonheterosexual suffragists, pushing them out of the movement or concealing their queerness from public view.

Historians have worked to recover the queer past, piecing together stories from the remnants.

Even after the ratification of the 19th Amendment in 1920, suffragists continued to foreground respectability politics in how they framed the narrative of the history of the movement. Suffragists who lived into the era after World War II were especially concerned about concealing their queer lives, given the increasingly homophobic and transphobic climate. In what has since become known as the Lavender Scare, from the late 1940s through the 1960s the federal government sought to root out and purge homosexuals from government employment. The pathologizing and criminalization of same-sex relationships, transness, and gender nonconformity further drove queer people into the closet. Aging suffragists hid aspects of their own pasts, sometimes even burning their photographs, diaries, and letters. Others found their stories obscured in the public record, as descendants, archivists, and biographers sanitized the lives of queer suffragists.

From the 1960s onward, successive waves of gay liberation, lesbian feminist, and transgender rights movements broke out of the closet and pushed back against historical erasure. Historians have worked to recover the queer past, piecing together stories from the remnants. My own research on the queer history of the suffrage movement was an act of recovery that required a careful interpretation of the archival silences and meticulous search for what had been concealed from the record.

Given our knowledge about this long history of erasure and recovery, the Trump administration’s recent efforts are not especially surprising but they are even more reprehensible. When I contacted NPS to object to the changes made to my article and demand the restoration of the original version, they told me that the alterations were made in an attempt to comply with federal orders. Rather than keep the edited version of the article on their website, they would remove it entirely. Since then, more than 200 NPS webpages have been edited to delete references to transgender or genderqueer people. More than 100 additional articles and research studies have been removed from the website entirely, including LGBTQ America (2016), an extensive theme study written by over 30 historians and published by the National Park Foundation.

This current wave of erasure is happening within the context of a much larger “Rainbow Panic” in the 2020s. Riding a wave of far-right extremism and Christian nationalism, Lavender Scare–era fears of queer people as sexual deviants have been resurrected to foment a new moral panic portraying trans people as “groomers” intent on harming children. Republican-dominated state legislatures have passed hundreds of anti-trans laws, criminalized drag performances, censored books, banned pride flags, and sponsored “Don’t Say Gay” laws restricting the teaching of LGBTQ+ history. Right-wing commentators, podcasters, and social media influencers have doxxed educators and LGBTQ+ community members, deliberately inciting online harassment and real-life violence against them. Trump’s re-election in 2024 provided a national platform for the Rainbow Panic, unleashing a new wave of vitriol against the LGBTQ+ community with the full weight and force of the federal government behind it.

This current wave of erasure is happening within the context of a much larger “Rainbow Panic.”

Historians have collaborated on efforts to contextualize this moral panic and resist attempts to erase history. The LGBTQ+ History Association issued a statement in February 2025 identifying the recent erasures as “part of a much part of a much broader pattern of attacks on, but not limited to, the history profession and teaching of accurate and diverse history.” The American Historical Association and Organization of American Historians have likewise issued a joint statement decrying the erasure of history. Meanwhile, archivists and scholars of LGBTQ+ history have worked to salvage and preserve the research that has been purged from government websites to ensure it remains accessible to the public, housing it on sites such as OutHistory. Individual scholars have also worked to educate the public through op-eds, podcasts, and social media in hopes of mobilizing people to action. A group of former and current NPS employees known as the Resistance Rangers have launched their own effort at recovery through the webpage Uncensored. Objecting to “the removal or deceitful editing of topics concerning transgender and queer experiences,” they have used the Wayback Machine to collect censored NPS pages.

But there is still so much more that history professionals can do to protect scholarship and to counter the rising tide of authoritarianism. We must join together in collective effort across historical associations, museums, archives, libraries, and public agencies to oppose orders dictating the historical topics we can archive, research, write, and teach. We must mobilize to defend universities and public institutions from government attempts to disrupt funding, weaken our self-governance, and dilute our curriculum. We must build interdisciplinary coalitions with professionals in other scholarly fields (including science, medicine, and law) to challenge the silencing of scholars and the censorship of all types of scholarship. We must raise our voices in unison to resist these injustices before it is too late.

Wendy Rouse is professor of history and coordinator of the Social Science Teacher Preparation program at San Jose State University. She is the author of Public Faces, Secret Lives: A Queer History of the Women’s Suffrage Movement (NYU Press, 2022).

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.