Where did the internet come from? If you guessed ARPANET, or the Advanced Research Projects Agency Network, you would be in agreement with most popular and journalistic accounts of how the internet was created. And, to an extent, you would be right. A packet-switching network that connected computers across the United States in the late 20th century, ARPANET, as Camille Paloque-Bergès and Valérie Schafer wrote in the introduction to a special issue of Internet Histories published earlier this year, is commonly “celebrated as the ancestor of the Internet.” (For the uninitiated, packet-switching involves breaking up data into smaller parts that are sent over a network and then put back together at the other end.)

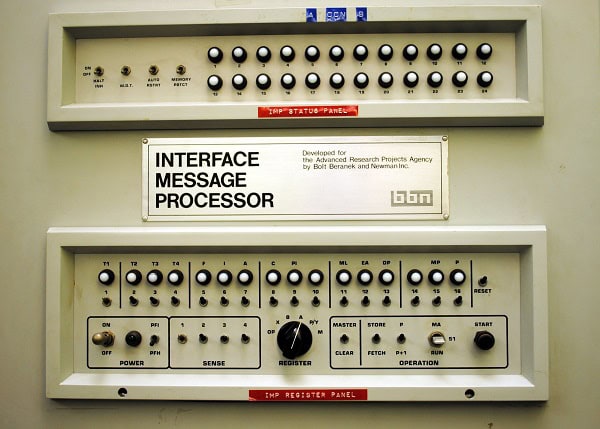

The Interface Message Processor connected UCLA to ARPANET, and relayed the first message between UCLA and Stanford. FastLizard4/Wikimedia Commons/CC BY-SA 3.0

It was over ARPANET, in October 1969, that programmers in labs at the University of California, Los Angeles, and Stanford University exchanged the first computer-to-computer message: “LO” (an unintentionally truncated form of L-O-G-I-N). But 50 years later, as the world gears up to commemorate the anniversary of that first message, historians of technology say there’s more to the story of the creation of the internet than the development of ARPANET. Instead, they point to networks built either elsewhere in the United States or around the world that also played key roles in the history of computer networking. ARPANET is still important, but is no longer the starting reference point in the history of the internet as it once used to be, they say.

Scholars are also veering away from “great man” narratives focusing on the biographies of inventors, often white men, that accompany the retelling of internet history. Instead, they’re calling for an expanded effort to include women and people of color as well as those who used the early network or who helped keep it functioning. This attention to diversity, scholars say, will bring forth more nuanced perspectives on the history of the internet and illuminate aspects of its importance that go beyond the technical.

The internet is related to but distinct from the World Wide Web. A simple, technical way to define the internet is as a global network connecting computers, phones, printers, and other devices—a “network of networks” as Andrew Russell (SUNY Polytechnic Inst.) described in an email. The World Wide Web, on the other hand, is a collection of web pages that are accessed via the internet. ARPANET was developed by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency at the Department of Defense. The network, launched in the late 1960s, was created “not for direct military use, but to connect their civilian researchers who were at different universities,” explains Janet Abbate, professor of science, technology, and society at Virginia Tech and author of Inventing the Internet (1999), one of the first histories of ARPANET and the internet.

ARPANET is no longer the starting reference point in the history of the internet.

Many popular accounts of the development of the internet follow a “linear progression,” with ARPANET as the point of origin, Russell explains. This “narrow history,” he says, traces events from the creation of ARPANET in the 1960s to the delineation of the Transmission Control Protocol/Internet Protocol (sets of rules for how data can be shared over the internet) to the development of the web to “commercialization in the 90s.”

But scholarly histories have moved on. Recent work, for example, has focused on the development of networks other than ARPANET. In Cybernetic Revolutionaries: Technology and Politics in Allende’s Chile (2011), Eden Medina (Indiana Univ.) writes about the development of Project Cybersyn in Chile. The purpose of the project, Medina explained to Perspectives, was to help Salvador Allende’s socialist government “nationalize the most important industries of the economy.” According to Medina, the government wanted to use a computer system to gather and visualize data, and design “new communication channels” that would enable it “to make management decisions on a national scale.” The project began in 1971 and ran until 1973, concurrent with the development of ARPANET but completely independent of it.

Medina argues that examining Project Cybersyn reveals the history of computer networking as a “global history.” “When people think about computer networks and the internet, very quickly they think of it as a US technology,” she says, “but there were these other networking efforts that were taking place at around the same time.” Scholars are also researching the development of networks in other countries, such as France and the USSR. Benjamin Peters, for example, in How Not to Network a Nation: The Uneasy History of the Soviet Internet (2016), documents the Soviet Union’s unsuccessful attempts to develop a nationwide computer network around the same time ARPANET was being built. Russell and Valérie Schafer have also highlighted the significance of the Cyclades project, which sought to influence the development of computer communication in France. Although this French computer network was never directly connected to ARPANET, engineers on both projects communicated with each other frequently. The Cyclades project ended in 1979 due to financial and political concerns but had lasting effects on the type of network on which the internet is based.

Scholars have also started looking at other neglected aspects of internet history. Traditional histories of technology focus on innovators, the people who pioneer new technological systems. But Russell, who’s also the chair of the Special Interest Group for Computers, Information, and Society (SIGCIS) in the Society for the History of Technology, thinks the idea that there should be a “multiplicity of perspectives and origin stories and sources and interpretations” when it comes to the history of technology is now “mainstream” among scholars. He observes that in the SIGCIS community, “it’s harder and harder to tell the old-fashioned, biography-driven, great man stories.” Newer scholars are more interested in researching “the connections between computing and society, what role users had in repurposing computers, phenomena like maintenance and infrastructure in different settings, and repair in different settings,” he adds.

To tell some of these stories, Russell co-founded, with Lee Vinsel (Virginia Tech), the Maintainers movement, which highlights the contributions and significance of “maintainers”—those who perform the work of maintenance, repair, and upkeep of the infrastructure that keeps society running. “Making a large technological system like the ARPANET work,” for example, explains Russell, “really depended on ARPA’s and the contractors’ ability to keep things running.” The Maintainers movement has spawned conversations, articles, workshops, conferences, and a community of scholars that, according to its blog, is interested in asking why we “neglect both maintenance and Maintainers, the people who keep our societies going.” “We talk about the internet as this transformational innovation, but the fact is that without all of this maintenance work . . . the infrastructure would have never existed to get the internet to the point where it can be a reliable disruptive force,” says Russell.

“It’s harder and harder to tell the old-fashioned, biography-driven, great man stories.”

Abbate notes that there are other aspects of the history of ARPANET and the internet that have also been “conspicuously left out.” Lynn Conway, a pioneer in computer-chip design, argues that the scientific contributions of women and people of color have been erased from the historical record because they don’t often fit the profile of people expected to be the innovators. As Paloque-Bergès and Schafer write, “ARPANET still remains largely absent” from the main scholarly “contributions to gender-conscious histories of computing and networking.” When Abbate was writing Inventing the Internet, for example, she kept asking herself, “Where are the women? What’s going on here?” She eventually wrote a second book, Recoding Gender: Women’s Changing Participation in Computing (2012), focusing on women’s involvement in computer science and programming in the second half of the 20th century.

Despite this repositioning of ARPANET and the people who developed it, scholars still emphasize its significance. Abbate describes ARPANET as the “backbone, the original place for the American Internet.” She points to the defense department’s choice to solve the problem of how to connect their researchers at different universities across the United States with “a messy, heterogeneous system, instead of something that would be simple and standardized,” as influential in shaping future funding models for research. ARPANET was influential in other ways, too. Sandra Braman (Texas A&M Univ.), in a 2010 article for Information, Communication & Society, describes how in the early stages of development, computer scientists working on ARPANET, many of them graduate students, “realized that they needed to document their discussions, the information being shared, and the decisions about network design that were being made.” These requests for comments (RFCs), as they came to be known, continue to be used today in the technology and internet communities. Abbate characterizes the RFCs as “a democratizing communication mode,” promoting the idea that “everyone can contribute” and that the community of researchers is “not hierarchal.”

Fifty years on, ARPANET’s significance ultimately depends on perspective. When looked at from the standpoint of developing “hardware and the infrastructure,” says Abbate, “ARPANET seems very big in that history.” But “if you look at things like human activity [and] use,” she continues, “ARPANET is a smaller piece in a bigger history of human communication and technologically mediated communities.”

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.