It can be challenging to teach about the civil rights movement. For many reasons, from time constraints to lack of access to archives, the liberation struggle is often framed through its most prominent leader, Martin Luther King Jr. Now, thanks to a partnership between Duke University and the SNCC Legacy Project, an organization comprised of SNCC participants, teachers have access to the SNCC Digital Gateway. The digital exhibition and archive uses essays, documentary sources, and visualizations to dive deep into the workings of the youth-led Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). Throughout the 1960s and 70s, SNCC empowered black communities in the Deep South through grassroots organizing and planning actions such as freedom schools, sit-ins, and voting registration drives. The SNCC Digital Gateway offers students the opportunity to explore grassroots histories of the Civil Rights Movement while broadening their understanding of who accomplished social change and how.

The National Museum of American History in DC displays the counter segment where four African American college students staged a sit-in at a “whites only” counter at a store in Greensboro, NC in 1960. UserFan/Wikimedia Commons/CC BY-SA 3.0

The site offers users seven gateways into SNCC’s activism: About, History, Timeline, People, Inside SNCC, Map, and Resources. Because of the depth of the content, I’d recommend providing students with some initial guidance on how to engage with the project. While it might be tempting to go straight to the History gateway, I tell students to start with About and read “The Story of SNCC,” which provides a brief overview of the organization and how it fits into a constellation of organizations fighting for freedom.

Next, I encourage them to read the History gateway which focuses on major SNCC events from 1943 to 1969, including the sit-in at Greensboro and the Freedom Rides. The timeline helps students keep events organized and see them in a broader civil rights context while noticing organizational changes within the SNCC. The design suggests a static timeline, but it is much richer than it appears. For example, students can click on “1965–1969 Black Power Takes Power: Political & Economic Organizing” and learn about how the SNCC organized around issues of economic justice and came to support the anti-Vietnam War movement.

From here, I recommend letting students explore on their own. For example, the Timeline links to pages including expository essays and documents. Clicking on “SNCC makes contact in Lowndes County” leads to a brief and well-researched essay about the efforts of Stokely Carmichael and fellow SNCC organizer Bob Mants in the infamous Alabama county that typified the violence of white supremacy. The right side of the page includes primary documents such as an article about SNCC’s organizing in The Movement and a 1988 audiovisual interview with Mants where he reflects back on the events that took place in 1965. The materials include links to the institutional and private archives that provided the materials. Along with introducing students to primary documents, the project thus encourages students to explore the archives. It also shows students the importance of giving credit through citations.

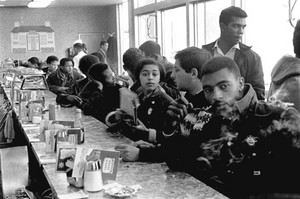

Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee members, who helped organize and inspire sit-ins across the South, meet at the Tottle House lunch counter in Atlanta in 1960. U.S. Embassy The Hague/Flickr/CC BY-ND 2.0

Other gateways include People, Inside SNCC, Our Voices, and Map. People brings attention to lesser-known activists and organizers like Martha Prescod (Norman). The page on Prescod, for example, helps illuminate the complexities of organizing through a short essay about her work as well as primary source materials including an oral and audiovisual interview. One possible assignment is to ask each student to select an interview of a woman and assess how race, gender, and sexuality constrained the revolutionary possibilities of SNCC.

Inside SNCC offers essays with documentary materials that address major themes such as governance, culture, political policy, and coalition building. This is particularly useful for helping students understand the organization’s structure as well as the central role of the arts through projects such as Freedom Singing and Free Southern Theatre. The Our Voices gateway has essays written by activists who reflect in the first person on their experiences. It also includes a rich collection of audio and video interviews with activists about Black Power. The latter in particular allows students to see activists reflecting back on SNCC, helping students see how historical actors framed their aims and accomplishments in the past and the present. The interviews can also help students learn how to assess oral histories. Teachers can ask students to compare how a person reflecting on their experience in 2016, like Jennifer Lawson, might frame their story and understanding of SNCC back in the 1960s. This might be of particular interest to those teaching about historical and cultural memory.

The Map section visualizes SNCC’s presence geographically. It allows students to immediately see a cluster of activities in Mississippi, where the organization concentrated its efforts. Clicking on a place brings the user to a page that lists the people and events in that location. Each name links to the People section, while an event brings users back to the Timeline. In fact, each of these gateways include in-text links that move the user across the site. The ability to click and move to another section of the site helps create a nonlinear narrative that encourages discovery and curiosity. A functionality ideal for teaching, students can move through the site creating connections across events, people, perspectives, and themes.

For instructors looking to link the 1960s to today, the Resources gateway is a great place to turn. Our recent presidential election has made clear that the road to ending racial inequality is anything but straight, and the struggle continues as exemplified by the Black Lives Matter movement. I have found students eager to discuss the connections they are seeing between the past and today, yet I want them to do so in a way that isn’t reduced to narratives of progress or claims that nothing has changed. The interviews with SNCC activists reflecting on their work in the intervening 40 years show that organizing for change is a continual and uneven struggle. Because the interviews are long, I’d recommend selecting short clips of three to four minutes and assigning them. Students can then discuss how the SNCC informed their later activism and also its continuing impact.

Whether interested in understanding SNCC in its moment or its legacies, the gateways build on each other to explain the intricacies of the organization and its role in the broader freedom struggle. One could easily use the project to focus several weeks of a course on SNCC or simply mine it for additional materials for a lecture. The hours of audio and visual material woven throughout the site are prime materials for close readings. The SNCC Gateway is, thus, an incredible resource for teachers and students alike who are looking to immerse themselves in the world of SNCC while learning about the broader grassroots organizing during the Civil Rights Movement.

This post first appeared on AHA Today.

Lauren Tilton is assistant professor of digital humanities and research fellow at University of Richmond’s Digital Scholarship Lab. She directs Photogrammar, a platform for visualizing photography, and is co-principal investigator of Participatory Media, a digital project exploring participatory community media from the 1960s. She is co-author of Humanities Data in R.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.