Our work with the National Park Service (NPS) began with an absence: the absence of an NPS framework for interpreting the Reconstruction era and of any site devoted to it. That absence seemed especially strange since the NPS has been, since the 1930s, the custodian of scores of Civil War battlefields, large and small.

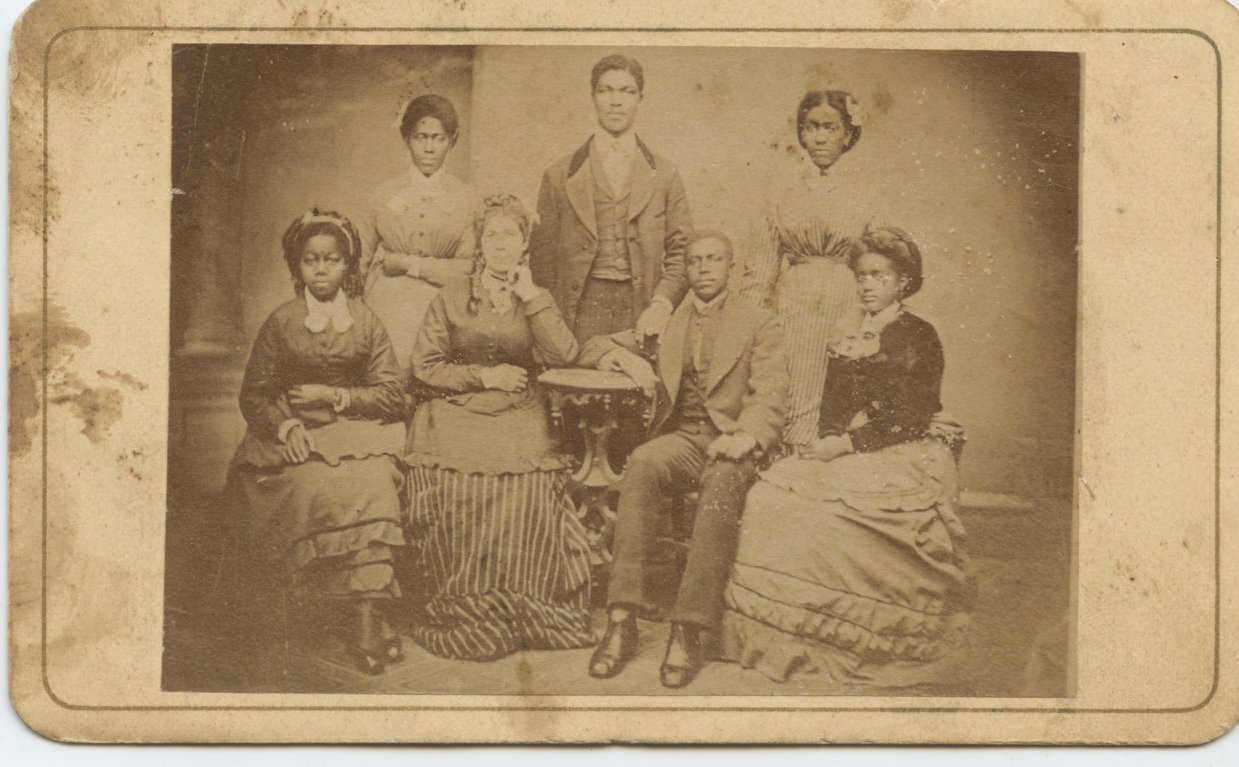

NPS staff, members of the congressional delegation, and park partners pose at the first anniversary celebration of the Reconstruction Era National Monument. Cadoff/National Park Service

When we approached NPS about working on Reconstruction in 2013, many professionals within the agency already had a strong appreciation for collaboration with academic historians and interest in drawing attention to the history of Reconstruction. We benefited from that sensibility as we worked with NPS staff on several projects. Our work convinced us of the deep professionalism and curiosity of many NPS officials and of the enormous benefits of working closely with the NPS in the sometimes-painstaking process of changing official interpretations.

The history of the Reconstruction era presents significant challenges, interpretive and otherwise. It was the period in which the United States finally outlawed slavery, Black Americans built new lives in freedom, and the nation adopted three amendments to the Constitution that today form the bedrock of individual rights. Many white Americans rejected Reconstruction’s democratic impulses and undermined them through means ranging from lies to corruption and terrorist violence. These were volatile years in which some of the largest questions of US history were front and center—questions of race, labor, democracy, and governance. The Reconstruction era’s endings and results were messy and ambiguous.

Reconstruction also inspired the most significant historiographical revolutions of US history, from the Dunning School’s early 20th-century overthrow of northern triumphalism to the Du Bois–inspired overthrow of the Dunning School. Starting in the civil rights era, many historians began centering the lives of formerly enslaved people, dismantling the myths of Reconstruction’s excesses, and engaging deeply with the limitations of the emancipatory project. But the older Dunning School view had made its way into the public consciousness, through inclusion in K–12 textbooks and influence upon film, television, and other popular culture. Not surprisingly, it also had infiltrated some NPS sites. Our goal was to help the NPS bring the updated history to the public. Our task was easier because of Reconstruction scholars’ enduring respect for Eric Foner’s foundational Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution (1988). We generally share a sense of what unites us even as our field continues to argue about key aspects of the period.

Many of us wondered whether Reconstruction’s sesquicentennial would receive any attention at all.

Our timing was shaped by our experiences during commemorations of the Civil War’s 150th anniversaries. From 2011–15, there were symposia, edited collections, and articles for the public on wide-ranging topics. Yet virtually none of those events or publications discussed Reconstruction, nor did institutions seem poised to continue their commemorations through Reconstruction’s anniversaries. Many of us wondered whether Reconstruction’s sesquicentennial would receive any attention at all.

We thought NPS officials might be interested in part because since the 1990s, the agency had dramatically changed its interpretation of the Civil War and had taken up topics it previously avoided. The more cynical among us might suspect that any time they visit a government-sponsored historic site, they are exposed to an “official history,” not the real history. And it is true that for most of its history, the NPS did not substantively grapple with tough topics in US history including slavery, Japanese incarceration, and Native American dispossession and genocide. But many within the NPS increasingly sought to update and broaden interpretations, often working closely with academic historians, in an effort to deliver up-to-date, accurate history that confronted challenging aspects of US history and also made sites appealing to diverse visitors.

A key turning point for Civil War interpretation came in 1998, when park superintendents of Civil War battlefields decided to move forward with a new vision focused on broader historical forces and the conflict over slavery instead of the traditional “guns and drums” interpretation that emphasized weaponry and battlefield maneuvers. An act of Congress in 2000 helped solidify the change, and in 2001 NPS convened a meeting with Civil War historians called “Rally on the High Ground,” designed to build collaboration between historians and the agency and help institutionalize the project of talking about the war’s causes and slavery.

The NPS faced significant pushback, receiving letters from angry Americans who denounced political correctness and historical “revisionism.” Within the NPS, however, supporters of the change felt that collaboration with professional historians helped the staff stand up to such attacks. A 2011 report on history in the NPS, written in collaboration with the Organization of American Historians, recalled, “NPS professionals, with the aid of the nation’s leading historians, held their ground, and disseminated these new points of view to audiences both near and far. This story of intellectual courage . . . continues to resonate through the agency today.”

All this was the broader context in 2013—midway through the Civil War sesquicentennial—when we began to inquire whether anyone in NPS would be open to talking with us about Reconstruction. We found that we were pushing on an open door when AHA executive director Jim Grossman introduced us to Bob Sutton, the NPS chief historian. Bob was entirely open to working with us and enthusiastic about the NPS again trying to tackle the challenge of commemorating Reconstruction. He and other NPS leaders remained convinced that the agency should confront sensitive topics, that visitors to historic sites should encounter up-to-date interpretations, and that collaboration with academic historians could help in both those areas.

In 2014, we collaborated with Bob Sutton and John Latschar on a Reconstruction handbook, modeled on one the NPS produced for the Civil War Sesquicentennial. That spring, the NPS Washington office gathered historians to draft a thematic framework for thinking about Reconstruction. In 2015, we signed on to write the National Historical Landmarks Theme Study on Reconstruction (published in 2017) with encouragement from and engagement with Turkiya Lowe, then regional chief of cultural resources (now NPS chief historian), and Michael Allen, an indispensable South Carolina–based NPS staff member.

NPS leaders remained convinced that the agency should confront sensitive topics, that visitors to historic sites should encounter up-to-date interpretations, and that collaboration with academic historians could help in both those areas.

Further context for our work was an already-existing effort to create a National Park devoted to Reconstruction in Beaufort, South Carolina. Late in 2000, at the end of the Clinton Administration, Secretary of the Interior Bruce Babbitt, together with Eric Foner and others, had worked on that project. They got as far as introducing the proposal in Congress, but it was defeated by Sons of Confederate Veterans’ lobbying of local congressman Joe Wilson.

By mid-2016, we were collaborating with NPS staff, the AHA, and other historical societies to encourage President Barack Obama to declare a national monument to Reconstruction in Beaufort before he left office. Local leaders and NPS staff did the hard work of negotiating the necessary operating agreements. A watershed moment occurred in December, when Representative Jim Clyburn and NPS director Jonathan Jarvis held a public hearing in Beaufort, and local residents and leaders expressed overwhelming support for the new monument. All these efforts were rewarded in January 2017, when President Obama issued a proclamation naming Beaufort and the surrounding area a national monument to Reconstruction. Congress made the monument an official national park two years after in an appropriations bill and also created the Reconstruction Era National Historic Network.

Our years-long experiences working with NPS professionals only reinforced what seemed clear when we began: the agency valued good history, written by people with training in historians’ methods of research and interpretation. NPS staff were curious, committed, and often extremely overworked. The people we encountered were public servants of the highest order who really cared about US history.

Beyond our desire to help bring the accurate history of Reconstruction to the NPS system and the broader public, we appreciated the collaborative aspects of working with NPS. We were energized by the rooms where people gathered to talk and sometimes argue about the past. We appreciated the NPS’s attention to historic sites themselves and were sometimes amazed by the experience of standing in a place where an event we’d only read about had actually happened. We were intrigued to see the many ways people have tried to capture the significance of a place with monuments and commemorative plaques. And we were moved by the deep connection many people felt with their local sites.

For us it was an immense honor to do historical work with and for the National Park Service and by extension, for the public that visits NPS sites to learn something meaningful and accurate—a public that trusts, or at least hopes, the US government will tell them the truth.

Kate Masur is John D. MacArthur Professor at Northwestern University. Gregory P. Downs is professor of history and department chair at the University of California, Davis.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.