It has been a memorable year for the city of Cleveland: the Cavaliers won the NBA championship; it hosted the RNC convention that nominated the man who is about to become the next President of the United States; and its baseball team almost won the World Series. The series loss was certainly a disappointment, but possibly not a problem given one of the defining characteristics of the city.

Downtown Cleveland. Wikimedia Commons

Since the 1950s, Clevelanders have learned to take pride in misfortune. As the city began to hemorrhage jobs and population and as the records of major sports teams echoed the economic woes, the t-shirt slogan of the day in the 1970s was “Cleveland: You Gotta Be Tough.” Minor catastrophe and misfortune became expected and were celebrated—a locally brewed beer, Burning River Ale, references the fire on the Cuyahoga River in 1969 that brought the city national attention and which, some contend, helped spur the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency. Three years later the mayor’s hair caught fire while he was opening an industrial convention by cutting metal ribbon with an acetylene torch. That too caught the nation’s attention but brought no remedial legislative activity. Self-deprecation and pride in withstanding adversity have been signifiers of local citizenship for nearly half a century.

That attitude now seems to be played out given what has taken place in 2016. Certainly, to be fair, there were bright spots in the years of gloom—yet this year has (on the surface at least) been different. The Cavaliers’ victory in the NBA playoffs brought the city its first major sports championship in 52 years. Shortly after the victory, the Quicken Loans Arena hosted the Republican National Convention—the third time the city (now solidly Democratic) has hosted the GOP (it did so in 1924 and 1936 at times when local political alignments were vastly different than today). That loyalty to the Democratic Party seemingly endured and made the city and surrounding Cuyahoga County a bright blue spot in a largely red Ohio in the November election.

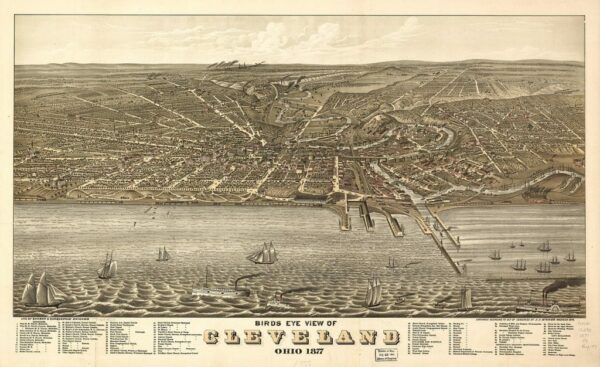

“Birds Eye View of Cleveland Ohio 1877,” Library of Congress/Wikimedia Commons

Then another Cleveland sports team, the Cleveland Indians, almost won the World Series. But the loss has not signaled a return to despair. That contest, even though ultimately unsuccessful, was—in my opinion—the high point of the year. Why? Because it combined multiple elements of the city’s historic mythos. Baseball has the deepest roots of any organized sport in the city. It speaks to a past that still resonates in a community that retains a great deal of generational continuity. It is not difficult to find a grandparent somewhere in the city who witnessed the last World Series victory in 1948, and even among newer residents there are large numbers of parents who could speak to their children with authority about the great team of the late 1990s that “almost did it.” If one were to measure memory by statues, the three that stand outside Progressive Field (the venue for the team) speak to these connections. They honor Bob Feller and Larry Doby who were stars in the late 1940s (with Doby having special significance as the first African American player in the American League), and Jim Thome, the slugger who sparkplugged the team in the 1990s. Even absent the ultimate victory, the season this year defied odds and expectations.

Certainly things, beyond success in sport, have changed in this city. As new, highly skilled workers come for jobs in a burgeoning med-ed and technology community (the largest employer in the city is the Cleveland Clinic), the most important change may be the new, fresh perspective they bring to an old city. The old neighborhoods they are “revitalizing” (including downtown) are the talk of the town and centers of a growing foodie culture. Ironically, it may have been this upscale shift that helped the area remain blue in the recent election. Certainly, the Democratic Party won most of the votes of the city’s large (53 percent of the city’s population) African American community, but it also gained the votes of many young professionals resident in the city and in several inner-ring suburbs. The blue-collar shift to the GOP seen elsewhere in Ohio seems to have been largely tempered by these factors in Cuyahoga County.

Yet, one needs to see beyond what could be called a veneer of image. The city’s poverty rate is one of the highest in the nation and its public school system still has problems, but seems slowly to be dealing with them. The racial divides in a city that is majority African American are significant, and the unskilled job market is small. Civic critics such as Roldo Bartimole, a journalist who has been observant and critical of the regional power structure for more than five decades, see major issues with the use of tax abatements as instruments of growth, and with municipal funding (via so-called sin taxes) to build and support venues for area sports teams. He and others argue that those “breaks” rob the schools and city of considerable funds or, alternatively, place a larger tax burden on the ordinary property owner and citizen. For many, being a Clevelander still entails a huge degree of toughness.

Certainly having a year like 2016 does drive a positive civic spirit in communities like Cleveland and as some would argue, civic spirit and a positive attitude can engender even greater change. Surprisingly the baseball team’s success has also opened another important issue—the fate of its cartoon Native American logo and even its name. That’s been a contentious issue locally, but now it has moved up several levels for a full discussion with the leadership of major league baseball. That may finally lead to a resolution that befits the sensibilities of the 21st century.

Home to the Cleveland Cavaliers, the Quicken Loans Arena in Cleveland, Ohio, also hosted the 2016 Republican National Convention. Wikimedia Commons

Nevertheless it is always important to put sports into perspective and the best way to do so it to keep in mind the words of the Roman poet Juvenal:

“… omnia, nunc se / continet atque duas tantum res anxius optat, /panem et circenses. (… everything, now restrains itself and anxiously hopes for just two things: bread and circuses).

Juvenal’s purpose was to comment on the decline in political involvement in Rome by noting how palliatives of entertainment and free bread led citizens away from their civic duties. Of course, the comparison is not one-to-one, but even absent free bread, sport still can become an escapist experience or contrarily an arena for the sometime violent expression of political and nationalist rivalries, as is the case on a number of international soccer pitches. In Cleveland though, sport still seems to function as a venue for civic pride and escape from the economic, political, and social realities that continue to confront the city and the nation.

That may be problematic in its own way. The realities that have been brought into clear focus by the campaign and election that followed the convention in Cleveland certainly have far more consequence than a 10th-inning loss in the seventh game of the World Series.

This post first appeared on AHA Today.

Dr. John J. Grabowski holds a joint position as the Krieger-Mueller Associate Professor of Applied History at Case Western Reserve University and the Krieger-Mueller Historian and senior vice president for research and publications at the Western Reserve Historical Society. He is the editor of the Encyclopedia of Cleveland History/Dictionary of Cleveland Biography (https://ech.cwru.edu).

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.