When a dozen Virginia Tech students began the course Topics in the History of Data in Social Context in January 2020, we expected that they would learn how to connect historical inquiry with statistical analysis—but we had no idea how their research on the 1918 influenza epidemic would become so relevant to our everyday lives. The course itself was a partnership between its instructor, Tom Ewing, a professor of history at Virginia Tech, and Jeffrey Reznick, the chief of the History of Medicine Division of the National Library of Medicine (NLM), who, with his colleagues, had planned to host an onsite workshop with the students late in the semester.

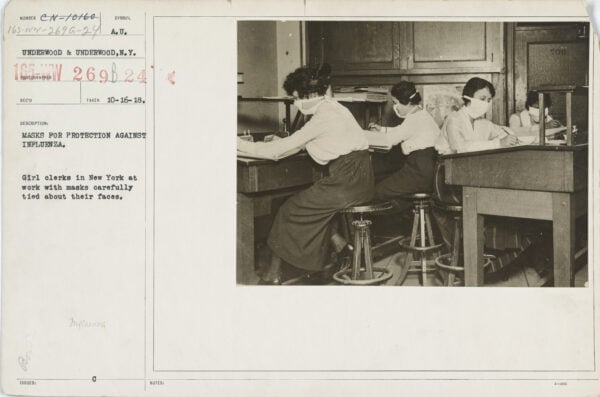

Students enrolled in the course Topics in the History of Data in Social Context combined their visual analyses of images like this one and medical data. National Archives and Records Administration, 45499337. Public domain

The outcome of this partnership was dynamic and impactful: students combined their visual analyses of images and data to build what the AHA’s Tuning Project describes as “empathy toward people in the context of their distinctive historical moments.” By studying quantitative evidence compiled in state department health reports and reported in local newspapers, students found ways to use their present experiences of living through a pandemic to deepen their appreciation for studying original source materials (and vice versa).

As historians, we are accustomed to exploring and surfacing layers of meaning embedded within historical sources of various formats, as well as combining sources to form new insights. Modeling this work with our students provided remarkable new insights as we looked more closely at one photograph of three clerks from the National Archives. The caption typed on the reverse of the original offers some useful information: “МАSKS FOR PROTECTION AGAINST INFLUENZA. Girl clerks in New York at work with masks carefully tied about their faces. Taken: 10-16-18.” However, this photograph has limits as a source: the “girl clerks” are anonymous and the business is not identified. The Sun newspaper published the photograph on October 27, 1918, with a similar caption: “Girl clerks at work with influenza masks to prevent the spread of the epidemic which has crippled many business houses.” We know this image circulated in public, but the newspaper provided no further information about these individuals. Therefore, the most useful clue was the date written on the reverse, which made it possible to locate this image in a specific moment of time during the epidemic.

Students combined their visual analyses of images with statistical data.

To understand the context of this photograph, we turned to the New York City Health Department’s monthly reports, which provided timely data on the epidemic. On October 16, 1918, the day this photograph was taken, New York City recorded 413 deaths from influenza. Daily influenza deaths rose from fewer than five prior to September 23, to nearly 100 by the first week of October. The 413 deaths reported on October 16 were four times this total, and the number would keep rising, although more gradually. The highest single day toll was reported on October 25, with 456 deaths. The chart, “Actual Daily Deaths from Influenza and Pneumonia, Epidemic of 1918,” published in the Monthly Bulletin of the New York City Health Department, shows this striking trajectory.

Statistics from the New York Board of Health provide additional evidence about the distribution of deaths by age and occupation that build historical empathy for the experience of these women. The 1918 influenza caused unusually high proportions of deaths among adults aged 20 to 40. In New York, 4,787 men and 5,213 women in this age group died from either influenza or pneumonia during the epidemic. The New York Health Department also reported deaths by occupation. “Office clerks,” the job category with the second-highest totals, recorded the deaths of 439 men and 289 women. This employment category accounted for more women’s deaths than any other occupation in the two months from September 14 to November 16. At the peak of the epidemic, we can estimate as many as 10 women clerks died each day from influenza. To be a “girl clerk” in fall 1918 in New York City was to be a member of a vulnerable population, a fact which is not evident from this photograph alone. We could only come to this insight by contextualizing it through contemporary statistics.

To be a “girl clerk” in fall 1918 in New York City was to be a member of a vulnerable population.

This course was always designed to bring the students’ research to a broader public audience, even before the COVID-19 pandemic meant that similar statistics appeared on a daily basis in most news outlets in 2020. During their research and in their presentations, which were livestreamed by the NLM, students addressed meaningful questions about the experience of individuals (such as the women in this photograph), the dilemmas facing public health officials (especially with regard to social distancing and mask wearing), and the methods by which people made sense of the epidemic once it was over. Given the shifts in their analytical framework and critical thinking, we can confidently conclude that students acquired more appreciation for how Americans in 1918 made sense of a rapidly changing situation requiring substantial changes in individual and collective behavior.

As scholars and public historians, we wonder what students 100 years from now will think of images of us in masks. Will they view screenshots of Zoom and think about them in the context of the CDC’s reporting? We, like many in the historical profession, spend a great deal of time asking what people in the past believed, thought, and understood, but we also can—and should—ask what people in the future might think about us and our circumstances as we wear masks to stay healthy today.

E. Thomas Ewing is a professor of history at Virginia Tech; he tweets @ethomasewing. Jeffrey S. Reznick is chief of the History of Medicine Division of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health; he tweets @jeffreysreznick.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.