About 15 years ago, I was teaching a high school AP World History lesson on early Christianity. In discussing the Council of Nicaea and the emergence of the Roman Catholic Church in the fourth century, I explained how church leaders from different regions had different practices. Once the church unified under Roman authority, they had to come together to hammer out common rules. These leaders even had to decide which scriptures to include in the Bible and which to exclude.

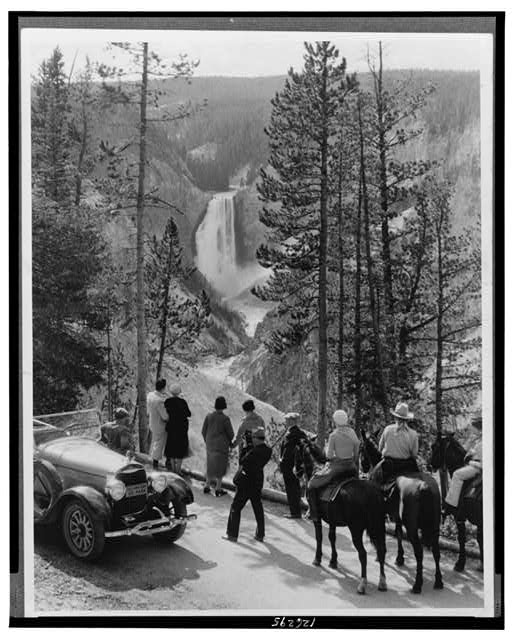

Teaching and learning is most successful when teachers, parents, and students all pull in the same direction. Lee Russell/Library of Congress/public domain

The next day, I received an email complaint about this lesson. A student, whose family were devout Christians who believed that the Bible was the inspired word of God, had come home confused by my secular approach.

This kind of conflict is inherent in history as a discipline. History, taught well, should challenge our preconceived notions. Challenge, albeit discomforting, makes any field of study interesting and dynamic. However, the tension between traditional belief and evidence-based historical scholarship is a special concern in a public school classroom. On one hand, teachers have a professional responsibility to adhere to the standards of the disciplines they teach—in my case, history. On the other hand, teachers have an ethical responsibility to construct inclusive environments for all students. It is a tricky balancing act.

Maintaining this balance requires considerable creativity on the part of the teacher and a positive and productive relationship with parents. The anecdote above offers an example of how this relationship should work. With more than 150 students, I cannot teach everything every parent wants me to teach. Nor can I exclude valid and relevant material because it may contradict a particular family’s beliefs. Concerns will arise. A skillful teacher in concert with dedicated parents can almost always resolve any conflicts that may arise from this tension.

The laws are vague about what constitutes a divisive concept, but critical analysis of race and gender is a central focus.

Regarding early Christianity, I was able to assuage the parent’s concerns by adding a simple caveat to my lesson that recognized students’ religious diversity as it relates to the historical approach to knowledge. Indeed, including this caveat improved my lessons by exposing my students to historical methodology and historiography. Students learned that history is not a dead subject requiring only rote memorization of facts. It is a discipline defined by a systematic approach. It is a good approach, but not the only approach. Most importantly, students learned that history is not just something that people study. It is what they do. History is something that students could aspire to do themselves.

However, recent legislation in Florida, intent on eradicating what has been labeled “woke instruction,” has changed the power dynamics and relationships between teachers and parents. SB 582, for instance, gives parents the power to challenge curricular material that they find objectionable. HB 1467 requires schools to post on their websites all book titles available to students, including in classroom libraries, and all instructional materials. Anyone in the school district, parent or not, can then contest these materials. Other laws restrict the content that can be taught. Most of these laws target social studies and history curricula and forbid discussion of so-called “divisive concepts.” The laws are vague about what constitutes a divisive concept, but critical analysis of race and gender is a central focus. Pride flags are certainly on the “divisive” list.

These laws have arisen alongside a small knot of parents who are convinced that teachers are indoctrinating their kids to reject God and patriotism. Advocacy groups like Moms for Liberty have organized those parents into a veritable posse. Empowered by what PEN America refers to as educational intimidation provisions, politically motivated parents have become self-appointed policing authorities over teachers.

These provisions are intimidating and conspicuously vague. Districts fear state reprisal and the loss of funding. Teachers are warned that they could face a third-degree felony if they allow ambiguously defined obscene or inappropriate material to fall into the wrong child’s hands. At the very least, teachers face the prospect of losing their certification, and thereby their ability to teach in the state. In Georgia, teacher Katie Rinderle was fired for reading the children’s book My Shadow Is Purple to her fifth-grade class. Hope Carrasquilla, a Florida principal, was forced to resign after a sixth-grade class learned about Michaelangelo’s David.

These cases are cautionary tales in an era when it feels like teachers are trapped in a panopticon. Any student may tell any parent anything that could result in disciplinary action. Parents could then bypass the teacher and report directly to higher authorities. These authorities then fall over themselves to assuage the parents. I have experienced this myself. In one case, a parent reported me when I offered an extra credit assignment requiring students to watch President Joe Biden’s State of the Union address (an assignment I offer every year, regardless of the president’s party). Another time, I was reported for a side comment I made during class change about the school’s active shooter policies.

With little direction from the state on how to implement these draconian laws, districts and teachers are on their own to defend themselves. Understandably, everyone errs on the side of caution. Teachers have removed books from their shelves. Posters have been stripped from walls. Lessons on critical thinking have been boxed up and replaced with anodyne, content-focused plans. Curricula are sterilized of anything even potentially controversial, so think twice about that Council of Nicaea lesson. Class debates are dangerous. When students have questions about current events in Gaza or Ukraine, or concerns about AI or inflation, it is best to redirect them to the day’s lesson. If one student says the wrong thing to the wrong parent . . .

If this sounds paranoid, that is the point. Paranoia encourages overreaction. In January, my principal had over 600 books removed from my classroom over the Martin Luther King Day long weekend. The catalyst was a text message to the deputy superintendent, in which a parent alleged that I was using “preferred pronouns” and allowing students to have unrestrained access to books. The district initiated a formal investigation to appease the parent. My principal responded by removing the books from my classroom. I responded by submitting my resignation, ending my 30-year career.

Currently, my district is debating a policy requiring all classrooms to be “viewpoint neutral.” The policy, if enacted, will task administrators with going from classroom to classroom to inspect all materials, including personal items, to ensure that none express any kind of viewpoint and that they align with the curriculum. But what is a “viewpoint-neutral classroom”? Nobody knows. Is it possible to teach narrative-rich topics like history without incorporating viewpoints? Would a poster from the US Holocaust Memorial Museum be considered to have a viewpoint, according to these policies? There is no clear answer. What is clear is that a small minority of ideologically motivated parents have their own ideas about “viewpoints,” and they will be watching.

Good teachers approach history with a viewpoint that frames their lessons.

History is not easy to teach well. The lessons are complex and often incomplete. Some stories are disturbing and involve addressing difficult-to-answer moral dilemmas. Historical narratives often challenge our beliefs. That is history at its best. Good teachers approach history with a viewpoint that frames their lessons. My viewpoint was to approach history as the chronicle of humanity’s quest for knowledge and freedom. With experience and creativity, the teacher can use this viewpoint not as an anchor, but as a platform by which students can develop and evaluate their own perspectives. Done well, students walk out of class inspired to dig further into history.

Framing one’s historical approach in such a way is not easy. It takes time to develop, and in the process, we make mistakes. Sometimes we fail to consider the diverse beliefs of our students, as I described. Sometimes we are too zealous about our points of view. But these mistakes are not indications of sinister motives. They are human errors that can be mitigated through human relationships. Only through open communication with parents can teachers maintain that delicate, three-way balance between teachers’ rights, students’ needs, and parents’ values.

It is impossible to teach history as a dynamic and exciting field in an atmosphere of scrutiny and paranoia. Many teachers will revert to memorization of facts amenable to bubble-sheet assessment. Essays and research papers that require critical thinking may be too risky. Better if the student never contends with ideas than be exposed to a dangerous idea. This scenario may be safer for the teachers, and more comforting for some parents, but in the process, students are being robbed of meaningful learning. And since high school students who learn that history is nothing but a mind-numbing recitation of facts do not become history majors, our society may be robbed of the next generation of brilliant, innovative historians.

Michael Andoscia is a former high school social studies teacher in Florida, a proud union member, and an advocate for teachers and students.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.