Fire rages across the global history of cities. From first-century Rome, to fifth-century Constantinople, 12th-century Hangzhou, mid-1400s Amsterdam, 1660s London, 1870s Chicago, and 1920s Tokyo, many of the world’s most economically, politically, and culturally significant cities have experienced major fires at one time or another.

The history of cities is often a history of fire. In May 2023, flames gutted the historic Manila Post Office. Manila Public Information Office/public domain

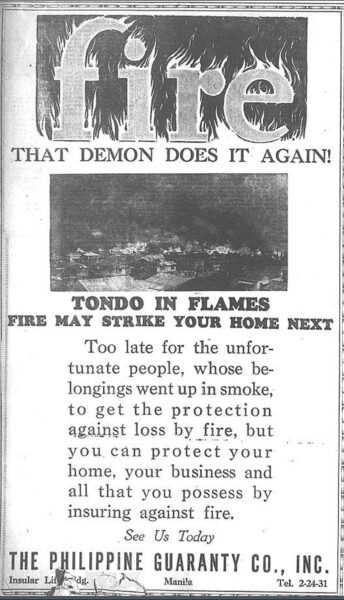

Within the setting of the Philippines’ American colonial past (1898–1946), one neighborhood in the capital city of Manila experienced numerous ruinous blazes that burned large areas of land. For instance, in April 1937, about 1,000 acres of homes were destroyed, and in May 1941, 20,000 people lost their homes. The fires were so frequent in the city’s district of Tondo that in the early 1940s a Filipino journalist described it as “a hussy who is incapable of learning her lesson.”

In recent years, blazes in Manila have not only continued to ravage untold numbers of residential properties; they have also affected heritage buildings. In May 2018, early 1900s edifices known as the Land Management Bureau Office and Juan Luna Building—the latter used by the National Archives of the Philippines to house documents—were damaged by fire. In February 2019, a blaze that raged for more than 10 hours caused extensive damage to the Bureau of Customs Building. Designed by the Filipino architect Antonio Toledo, the elegant late 1930s neoclassical edifice has been described as “arguably as beautiful as the Manila Post Office.” The Manila Post Office, a grand classical structure erected downtown in proximity to the south bank of the Pasig River, is widely considered the jewel in the local architectural heritage crown. In May of this year, a fire gutted that building too.

The Manila Post Office is widely considered the jewel in the local architectural heritage crown.

Constructed during the late 1920s to a design composed by the Filipino architects Juan Arellano and Tomás Mapúa, the Manila Central Post Office Building had become more than an inner-city landmark. Thanks to scholars and heritage advocates studying the evolution of Manila’s built fabric, the Post Office Building has come to represent a high point of the modern Filipino architectural narrative. And since the building’s architects were educated in North America, it has been viewed by heritage proponents as representative of the collaborative effort made by the American colonial state and Filipinos employed in the Bureau of Public Works to transform Manila into the “Paris of the East.”

The urban form of Manila, a metropolis of about 13.5 million people today, has evolved in such a manner that it is now defined by run-down properties, ugly high-rise office buildings, slums, and a lack of green open space. As such, to many Filipinos, Manila’s demographic explosion during the late 20th and early 21st centuries has led the Paris of the East to transform itself into paradise lost. Countless old buildings have, in the name of modernity and progress, fallen foul of the wrecking ball. As a result, evidence of Manila’s former splendor has become increasingly scarce. The burning of the Post Office Building has come to epitomize cultural loss, just as with recent fires that severely damaged the Monastère du Bon-Pasteur in Montreal, Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris, and the National Museum of Brazil in Rio de Janeiro, all of which triggered shock and upset that resonated far beyond the city limits.

Catastrophes have shaped the history of many cities, and infernos in particular have elicited a range of governmental responses and policy prescriptions in order to lessen the future risk of conflagration. In Manila, scholars such as Greg Bankoff have documented the frequency of catastrophic events in the city’s colonial history and recorded the state’s response to such misfortunes. But it is important for historians in particular to acknowledge the trauma that calamities generate among members of the public for two reasons.

First, the destruction of important structures provokes deep public interest in both the management and the preservation of old buildings. As the fire at Manila’s Central Post Office Building, which had been protected as “important cultural property” since the passage of Republic Act No. 10066 in 2009, demonstrates, Philippine laws to preserve historic structures have done little to stop edifices being razed or to compel their reconstruction after a fire. There is substantial popular speculation that the Philippine Postal Corporation will sell the burned structure to a private property developer so that it can be renewed into something else (e.g., a hotel). The general public has shown a great deal of concern as to whether the will exists to rebuild Arellano and Mapúa’s building in its original form.

Second, public authorities in the Philippines are usually very quick to downplay the fires that are repeatedly occurring in heritage buildings. Typically, they are labeled by local governments as “accidents.” However, for many heritage advocates, the term accident implies an inside job intended to legitimize a property owner’s claim that the previously run-down structure must now be demolished and replaced by a more profitable condominium. Hence, even though the presence of law provides for the protection of built heritage and contributes to the nation’s goal of achieving target 11.4 of the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals, occurrences of fire in Manila expose just how vulnerable the governmental strategy of attaining an inclusive, safe, and resilient form of urban development is.

Historians have much to learn about how those in Tondo have normalized inferno as part of their regular routine.

When fire strikes nationally important edifices, not only are distinct features within the cityscape lost, but a part of the country’s history literally and symbolically disappears. Consequently, expanding knowledge of the history of fire in Manila and elsewhere will do more than help explain how and why disastrous events have transpired. New inquiries expose the human decisions that have affected the built environment’s appearance and morphology up to the present day. They reveal whether places such as Manila contradict the concept of a fire gap—the notion that large conflagrations decline in occurrence as a city expands in demographic size.

Manila Tribune, August 19, 1938

When one considers any history of fire, numerous environmental and human factors must be taken into account. These include building materials; the height, volume, and density of buildings; susceptibility to natural disasters such as earthquakes; the character of the local climate; fire prevention ordinances; and local firefighting techniques. Cities, after all, each have their own fire regime. Therefore, as the general public in Manila grows increasingly concerned about the destruction of built heritage, the history of fire can help form new strategies that will help to better protect the city’s historic structures. Likewise, citizens can realize that occurrences of fire have been central to the global evolution of city governments and different types of agencies that lobby for social and environmental reform. Fire, historically, has led to the development of new ideas and policies to better manage cities and, so, ensure the maintenance of edifices identified as being of significance.

Ultimately, urban fire history in a city such as Manila deserves much greater attention. Without our studying how the nature of urban fire has changed through time, its relationship to human behavior and governmental decision-making will remain weak. Those residing in locales such as the Tondo, where today more than 650,000 people are crammed into just eight and a half square kilometers of land, will continue to live with the reality that life-threatening outbreaks of fire are, quite simply, routine. Historians have much to learn about how those in Tondo have, given past and present-day occurrences of fire, normalized inferno as part of their regular routine. When we recognize and learn from this intangible heritage, it will be possible to culturally neutralize other urban dwellers from any process in which the hitherto unusual and dangerous (to both one’s health and one’s sense of being of a nation) should, in the future, be normal.

Ian Morley is associate professor of history at the Chinese University of Hong Kong and vice president of the International Planning History Society.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.