As Americans head to the polls in November, voters face a firestorm of existential challenges at home—surviving a pandemic, fixing a broken health-care system, reviving a devastated economy, healing wounds of racial injustice and civil strife. The president’s effort to label COVID-19 the “China virus” notwithstanding, US-China relations barely seem to register on the barometer of burning and divisive issues. Nor do the China policy postures of the two leading candidates, Joe Biden and Donald Trump, offer the kind of sharp contrast that might tip the undecided mind—their differences seem to boil down to a choice between tough and tougher.

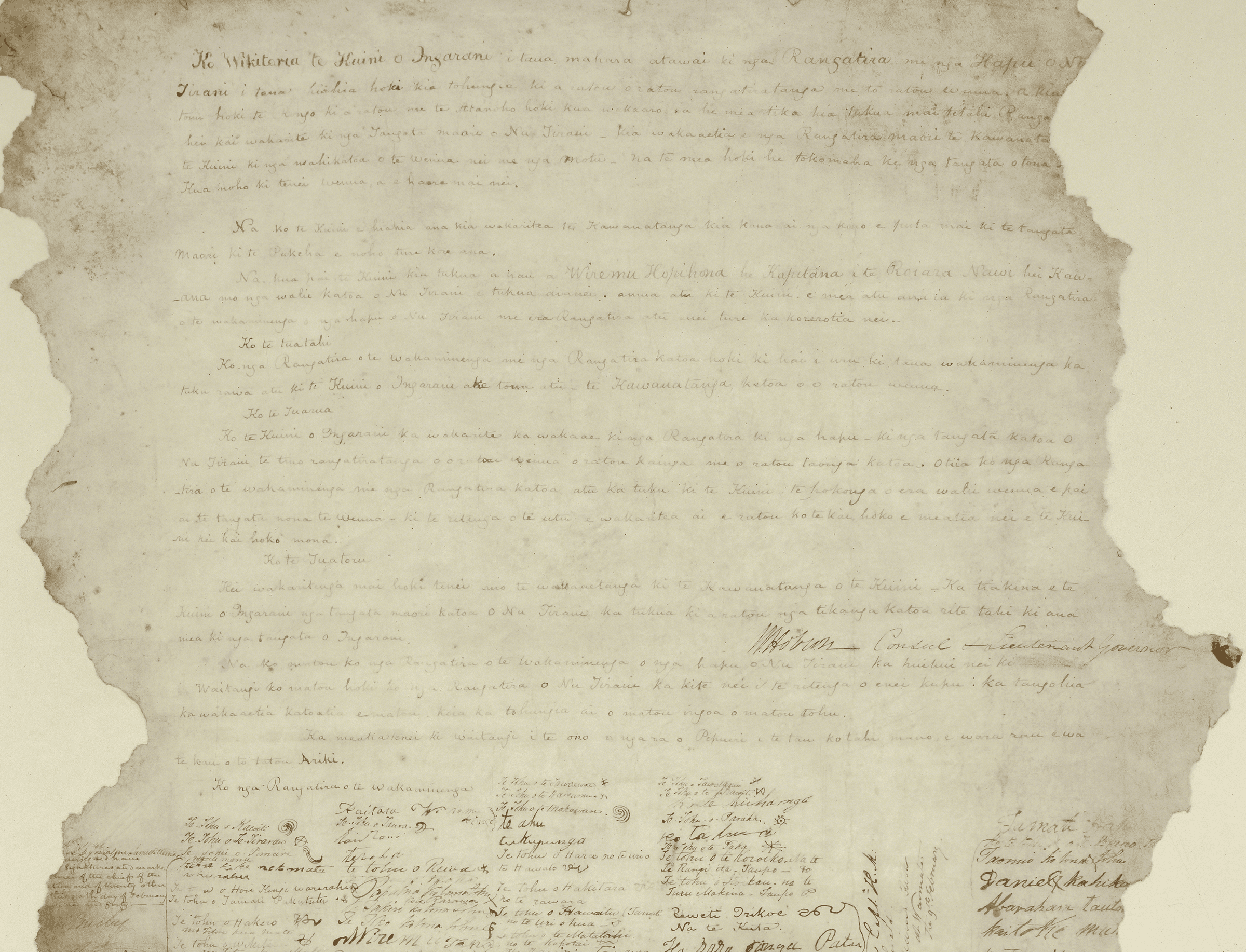

In August 2008, Beijing welcomed the world to a spectacular Olympic Opening Ceremony, a stunning display of China’s arrival as a first-world power. wuqiang_beijing/Panoramio via Wikimedia Commons/CC BY 3.0

And yet, a momentous shift is underway in how the United States as a nation perceives the People’s Republic of China, one that is likely to define the foreign policy possibilities of whoever wins in November. For the first time in centuries, Americans are looking upon China as an equal in terms of national wealth and power; and for the first time ever, the parity presents itself as a threat to the interests and security of the United States. By putting this perception of China as rival in historical context, we can appreciate just how novel and uncharted is the territory ahead for the two nations.

One has to travel quite a distance into the past to find the last time Americans talked about China as a “peer competitor” or a “near-peer,” in the current lingo of US defense officials. We need to go all the way back to the American colonial period and early republic, before the United States expanded across the continent and before the Qing Empire fell from its place as Asia’s hegemon. Through the 18th century, Qing China was the superior power—albeit far enough away that it posed no danger. The founders’ generation admired China as a prosperous land of porcelain, silk, and tea, an enlightened civilization governed by Confucian “literati.” The allure of the Qing economy was well-founded; if, as Kenneth Pomeranz shows in The Great Divergence, the wealthy regions of China were as well-off as England until at least 1750, the same would hold for North America as well.

The 19th century was as merciless to the splendor of the Qing Empire as it was fortuitous for the rise of the United States. Americans would gradually associate China not with enlightened governance and luxury manufactures, but with backwardness, poverty, and weakness. We might locate an unnoticed tipping point in a pair of dramatic attacks in the respective capitals that occurred within a year of one another: In September 1813, the Qing Emperor narrowly avoided an assassination plot in the Forbidden City; in August 1814, President James Madison had to flee Washington, DC, in advance of invading British troops. For the Qing Dynasty, the Eight Trigrams Rebellion of 1813 inaugurated a century of domestic rebellion and foreign invasion that would unravel its might and undermine its sovereignty. China suffered one humiliating defeat after another in the two Opium Wars, the Sino-French War in Indochina, the Sino-Japanese War in Korea, and the Boxer War, whereas for the United States, the War of 1812 was the last major foreign attack on American soil until Pearl Harbor. The United States grew into a first-rank imperial power able to defend hegemonic claims over the Western Hemisphere (the Monroe Doctrine) and what Daniel Immerwahr describes as a “hidden empire” of islands across the Pacific Ocean and a colony in the South China Sea—the Philippines.

As the United States rose and the Qing Empire declined, Americans’ perceptions of China underwent a fundamental shift. Missionaries encouraged their compatriots to pray for “heathen Chinese” (and support their own proselytizing efforts). Merchants lobbied their government to prop up the Qing regime so they could continue doing business out of treaty ports like Shanghai. Politicians whipped up xenophobic sentiments, blaming Chinese immigrants for stealing jobs and driving down wages for “native” (i.e., white) Americans. Whether coming from a place of pity, greed, or scorn, Americans looked down on China as the “sick man of Asia,” in the fin-de-siècle phrase popularized by reformist intellectual Liang Qichao.

A momentous shift is underway in how the United States as a nation perceives the People’s Republic of China.

China’s chaotic experiences in the first half of the 20th century—revolution, warlordism, invasion by Japan, and civil war between Nationalists and Communists—only reinforced Americans’ image of China as needing their help. As historian Gordon H. Chang details in Fateful Ties: A History of America’s Preoccupation with China, many Americans felt a special responsibility for China’s fate. Raising a family in 1940s San Francisco, my grandmother, who escaped poverty in Ireland for the promise of the American Dream, would guilt-trip my mom and uncle into finishing their dinner with the injunction to “think of the starving children in China.” Perhaps she had read Pearl S. Buck’s bestselling novel The Good Earth or seen the 1937 film version. During World War II, she could not have avoided propaganda celebrating America’s heroic allies in Free China.

Feelings of sympathy evaporated in 1949 when Mao Zedong’s Communist Party founded a Soviet-allied state, the People’s Republic of China. Americans’ fear of “ChiCom” aggression and subversion displaced the sense of pity or goodwill. But this did not qualify China as a “near-peer,” even when its soldiers drove US troops out of North Korea in 1950. China was dangerous because, in its weakness, it had come to serve the Soviet master—America’s rival was the USSR, not the PRC. Senator Joseph McCarthy preyed on such fears, choosing the China scholar Owen Lattimore as the first victim in his smear campaign, accusing Lattimore of being the “top Soviet agent” in America. Fears of subversion took on an apocalyptic aspect when Beijing developed atomic weapons in the 1960s, but joining the nuclear club did not make China an equal, either.

Even the diplomatic breakthrough of Richard Nixon’s visit to Beijing in 1972 did not alter the underlying American perception of China as a lesser power. The Nixon-Mao détente transmuted fears into hopes for cooperation against the Soviets and opened the door to restoring some spirit of friendship between the two peoples. But the positive dynamics generated by “normalization” were buoyed, on the American side, by the perception that China was trying to “catch up” to the West and become more like America. This hope reached its apotheosis in 1989 when Chinese students paraded a homemade Goddess of Democracy, sculpted in the likeness of the Statue of Liberty, through Tiananmen Square. After Deng Xiaoping brutally crushed the democracy protests on June 4, some Americans still believed that China’s modernization would inevitably lead to liberal democracy; others became reconciled to a China stuck in a retrograde system of Leninist authoritarianism. Either way, China was perceived as a lesser organism in the evolution of political species.

A couple of years after the trauma of Tiananmen, Deng managed to revive his economic strategy of “reform and opening”—under stricter party control—and China’s explosive growth became its defining feature for the world. Americans came to see China as one giant factory churning out low-priced goods and using the proceeds to buy trillions of dollars in Treasury bills that subsidized America’s national debt. The pace and scope of China’s development in the late 20th and early 21st century was staggering. It was this “China boom” that set in motion a fundamental transformation in the American image of China.

For the first time in centuries, the United States is looking at China as an equal and doesn’t like what it sees.

Again, we might choose a pair of events that marked off divergent trajectories for the century to come: In August 2008, Beijing welcomed the world to a spectacular Olympic Opening Ceremony, a stunning display of China’s arrival as a first-world power. Weeks later, Wall Street unleashed a global financial crisis, and the Federal Reserve had to bail out insurance giant AIG, a company founded in treaty port Shanghai in 1919 by an American businessman.

In the dozen years since, China’s economic growth, military spending, and diplomatic influence have advanced inexorably, even as its political system shows no sign of “convergence” toward the American model. Barack Obama entered office hoping to cooperate with Beijing on global challenges like climate change and nuclear nonproliferation, but in his second term ended up announcing a “pivot to Asia” to contain China’s rise. The Trump administration defined China as a peer competitor and national security threat from day one, and by year four had launched a trade war and ideological campaign against the “Frankenstein” of a wealthy and powerful China.

With the November election looming, the Trump administration stoked old fears of Chinese subversion, casting students, journalists, diplomats, and Communist Party members and their families as targets of suspicion. Liberals blush at the hawkish excess, but—disturbed at detention of Uighurs in Xinjiang and repression of democrats in Hong Kong—agree with the need to push back. Underlying these policy debates is a deeper, historical shift. China is no longer visible in America’s rearview mirror. For the first time in centuries, the United States is looking at China as an equal and doesn’t like what it sees.

Additional Resources Suggested by :

Asian Americans, produced by Renee Tajima-Peña (2020; Washington, DC: WETA Washington, DC, and the Center for Asian American Media), online streaming

Gordon H. Chang, Fateful Ties: A History of America’s Preoccupation with China (Harvard, 2015)

ChinaFile, an online magazine about topics related to the changing relationship between the United States and China, produced by the Asia Society Center on US-China Relations

Daniel Immerwahr, How to Hide an Empire: A History of the Greater United States (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2019)

John Delury is professor of Chinese studies at Yonsei University Graduate School of International Studies in Seoul, South Korea. He tweets @JohnDelury.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.