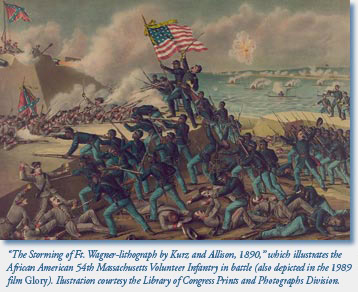

Hollywood’s engagement with the American Civil War illuminates changes in popular understanding of the conflict. I have been especially intrigued by the relationship between cinematic treatments over the past two decades and four interpretive traditions established by participants in the war. Films that have dealt with Civil War themes since the appearance of Glory in 1989 afford excellent material to pursue these connections. The roster includes Dances with Wolves (1990), Gettysburg (1993), Sommersby (1993), Pharaoh’s Army (1995), Ride with the Devil (1999), Gangs of New York (2002), Gods and Generals (2003), Cold Mountain (2003), and Seraphim Falls (2006). As a group, these movies suggest that Hollywood, which earned its greatest Civil War-related profits from The Birth of a Nation (1915) and Gone with the Wind (1939), increasingly shuns the pro-Confederate sentiment of those blockbusters and many later films in favor of an emancipation narrative that discredits the importance of Union as a motivating factor for the North.

Hollywood’s engagement with the American Civil War illuminates changes in popular understanding of the conflict. I have been especially intrigued by the relationship between cinematic treatments over the past two decades and four interpretive traditions established by participants in the war. Films that have dealt with Civil War themes since the appearance of Glory in 1989 afford excellent material to pursue these connections. The roster includes Dances with Wolves (1990), Gettysburg (1993), Sommersby (1993), Pharaoh’s Army (1995), Ride with the Devil (1999), Gangs of New York (2002), Gods and Generals (2003), Cold Mountain (2003), and Seraphim Falls (2006). As a group, these movies suggest that Hollywood, which earned its greatest Civil War-related profits from The Birth of a Nation (1915) and Gone with the Wind (1939), increasingly shuns the pro-Confederate sentiment of those blockbusters and many later films in favor of an emancipation narrative that discredits the importance of Union as a motivating factor for the North.

I focus on the period beginning with Glory because it witnessed a significant expansion of interest in the Civil War among filmmakers after a relatively dormant period between 1965, when the war’s centennial ended, and the mid-1980s. Hollywood’s increased attention was no doubt inspired, at least in part, by the conflict’s heightened visibility within the general populace. A round of 125th anniversary celebrations that commenced in 1986, well-publicized disputes over threatened development at historic sites such as Manassas, and, most important by far, the airing of Ken Burns’s documentary, The Civil War, in 1990 created a potentially significant audience for movies dealing with the war.

Hollywood responded with productions that embraced to varying degrees the Civil War generation’s four major interpretive traditions—each of which can be sketched quickly. Ex-Confederates who established the Lost Cause tradition portrayed an admirable struggle against hopeless odds, denied the importance of slavery in bringing secession and war, and ascribed to themselves constitutional high-mindedness and gallantry on the battlefield. The Union Cause tradition, which predominated among white northerners, portrayed the war as an effort to maintain a viable republic in the face of secessionist actions that threatened both the work of the Founders and, by extension, the future of democracy in a world that had yet to embrace the concept of self-rule. The Emancipation Cause tradition, preeminently the work of African Americans but also embraced by some white northerners, interpreted the war as a struggle to liberate four million slaves and remove a cancerous influence on American society and politics. Finally, the Reconciliation Cause tradition represented an attempt by white people North and South to extol American virtues that both sides manifested during the war, exalt the restored nation that emerged from the conflict, and mute the role of African Americans.

Union, emancipation, and reconciliation overlapped in some ways, as did the Lost Cause and reconciliation. Yet each of the four offers a quite distinct attempt to explain and understand the war. Union and emancipation expressed joy at the destruction of the Confederacy but often diverged in discussing the end of slavery. For the Union Cause, emancipation represented a tool to punish slaveholding oligarchs and undermine the Confederacy; for the Emancipation Cause, it stood as the most important, and ennobling, goal of the northern war effort. Union and reconciliation similarly lauded the fact that one nation emerged from the conflict. Yet unlike reconciliationists, who avoided discussion about which cause was more just, supporters of the Union never wavered in their insistence that Confederates had been in the wrong. Adherents of the Lost Cause and reconciliation could agree to ignore the centrality of emancipation, but many former Confederates, whatever their public rhetoric about loyalty to the reunited nation, persisted in celebrating a struggle for southern independence that had nearly undone the Founders’ efforts.

As I sought cinematic evidence of the four traditions, I remained fully aware that Hollywood’s overriding goal is to provide entertainment that will earn profits. Studios, producers, and directors seldom have a didactic purpose. They focus on plots and characters that create and sustain dramatic momentum. No one in Hollywood would insist that a historical drama, above all, reflect the insights of the best recent scholarship—at least not anyone who hopes to attract and satisfy paying customers. The complexity of scholarly investigation translates poorly to the screen. Freddie Fields, who produced Glory, spoke directly to this point in 1989. Reacting to complaints that the film got some historical details wrong, he observed: “You can get bogged down when dealing in history. Our objective was to make a highly entertaining and exciting war movie filled with action and character.”

Yet films undeniably teach Americans about the past. Almost certainly, more people have formed ideas about the Civil War from watching Gone with the Wind than from reading books written by historians. Even moderately successful movies attract a far larger audience than the most widely read nonfiction books dealing with the conflict. Whether intentionally or not, films convey elements of the four interpretive traditions, and how well each has fared sheds light on their comparative vitality.

My exploration of cinema over the past 20 years yielded two key findings. First, as already noted, Hollywood increasingly shuns the Lost Cause. Since the release of Glory, only Gods and Generals takes a predominantly Lost Cause interpretive stance—though some scenes in Gettysburg also would meet the United Confederate Veterans’ standards of practice. Leading white southern characters in films such as Sommersby, Ride with the Devil, and Cold Mountain oppose slavery, embrace emancipation, and manifest quite modern sensibilities about race. This trend aligns with, and probably grows out of, the post–civil rights movement shift away from public displays of the St. Andrew’s Cross battle flag and other Confederate symbols. It also represents a good deal of historical wishful thinking on the part of filmmakers, as when Ada Monroe, daughter of a slaveholding physician from Charleston in Cold Mountain, announces upon arriving in western North Carolina that she is happy to escape from “a world of slaves and corsets and cotton.” Abolitionists Sarah and Angelina Grimké notwithstanding, it must be said that very few women from slaveholding families in South Carolina would have agreed with Cold Mountain‘s heroine.

A second and more surprising finding confirms the weak presence of the Union Cause in movies. The most widely embraced of the four traditions by the wartime generation, it lags far behind emancipation and, to a lesser degree, reconciliation. No scene in any recent film captures the abiding devotion to Union that animated huge numbers of soldiers and civilians in the North. This is somewhat understandable. Long pieces of explanatory dialogue about Union as an emotional and political focus would halt narrative momentum. Yet a number of films demonstrate what a single scene could accomplish. In Casablanca, the singing ofLa Marseillaise in Rick’s bar as the camera moves from one passionate face to the next communicates devotion to a French nation humbled by German military power. More to the point, Gone with the Wind‘s fancy ball, staged with Confederate flags and a huge portrait of Jefferson Davis much in evidence, creates a strong sense of the kind of national purpose that would prompt women such as Melanie Wilkes to contribute their wedding rings to support southern armies.

Union Cause advocates of the Civil War generation would be most alienated by Hollywood’s negative depiction of white northern soldiers. Scenes in Glory, Dances with Wolves, Pharaoh’s Army, Cold Mountain, and Seraphim Falls promote a vision of the Union army remarkably like that of United States military forces in Vietnam as imagined by Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now (1979), Oliver Stone’s Platoon (1986), Stanley Kubrick’s Full Metal Jacket (1987), and Brian De Palma’s Casualties of War (1989). More often than not, white Union soldiers appear as cruel and destructive racists who abuse black people, Confederate civilians, and Native Americans. This post-Vietnam phenomenon would prove vastly pleasing to neo-Confederates who prefer their northern soldiers in the mold of the looter/rapist killed at Tara by Scarlett O’Hara in Gone with the Wind (an unintended consequence almost certainly lost on the directors of some recent films).

Why have the Union Cause and its military forces reached such a point? Part of the answer lies in the nebulous nature of a fight to save “the Union.” The other two northern traditions lend themselves to simple formulations: emancipation meant freeing the slaves, and reconciliation meant bringing Americans back together after a period of sectional alienation and slaughter. Both traditions focus on clear outcomes almost all modern Americans see as desirable. A tougher challenge awaits anyone who tries to explain why “Union,” a word and concept no longer part of our political vocabulary, mattered so much. In a nation that has stood first among world powers at least since World War II, most Americans cannot imagine an internal threat of the kind that galvanized the northern people in 1861. Both students and adults often ask why hundreds of thousands of northern men, in the absence of a challenge to their immediate well-being (Confederate armies never threatened to conquer large chunks of United States territory), risked their lives to safeguard the work of the Founders and preserve America’s democratic example to the world. Yet anyone who fails to appreciate that untold citizens believed Confederate independence would scuttle the American experiment cannot grasp what was going on in the North.

Ambivalence about the kind of nation that developed after the war exacerbates the problem. For most Americans, the Union, with its factories and large population and substantial urban development, looks very much like the current United States. Unhappiness with various dimensions of the modern state often translates into a harsh critique of the Union. For example, conservatives and libertarians sometimes accuse Lincoln and the Republicans of using the war to build a mighty and intrusive state—thereby robbing the Union Cause of any uplifting purpose. Some Americans unhappy with the global projection of United States military and economic power in the years since the end of World War II credit Union victory with making possible an avaricious state that embarked on imperialistic ventures. This formulation has allowed Hollywood to treat United States armies, whether rampaging through the Confederate countryside or in Vietnam, as largely malevolent expressions of national policy.

It is too soon to tell how the war in Iraq might shape Hollywood’s handling of the Civil War. For now, anyone knowing little about the conflict would come away from recent films with the strong impression that almost all admirable characters wage a war for emancipation. Apart from those devoted to ending slavery, white northerners subscribe to no guiding set of principles—certainly nothing connected to the Union. In some cases, Union soldiers manifest a sense of comradeship with their Confederate foes, touching on points of commonality between North and South and seemingly trapped in a conflict not of their choosing. In sum, viewers will find strong echoes of the Emancipation Cause and to a lesser extent of the Reconciliation Cause. They will not form any appreciation for the Union Cause. As for the Lost Cause tradition, it likely enjoyed its last hurrah in Gods and Generals. Residual influence will rest with television, where Gone with the Wind and other films with Lost Cause themes are always available, and in the availability of older films in other formats.

Gary Gallagher is the John L. Nau III Professor of History at the University of Virginia. His most recent book is Causes Won, Lost, and Forgotten: How Hollywood and Popular Art Shape What We Know about the Civil War, published by the University of North Carolina Press in April 2008.