Driving down south from Keetmanshoop toward Grünau on southern Namibia’s B1 trunk road, it’s common to spot small mammals hustling across the highway from one stony outcropping to another as the road weaves through the Karasberge (Karas Mountains). These are rock hyraxes (Procavia capensis)—known in Southern Africa as dassies—and despite being completely herbivorous, they were classified as vermin in Namibia under apartheid.

As I was reading through the files of the South West Africa Division of Nature Conservation & Tourism (Afdeling Natuurbewaring en Toerisme; NTB) to get a better understanding of research conducted on carnivores, I came across a number of files with labels that translated to “Problem Animal Research: Dassie Ecology and Control.” The files seemed a bit out of place among folders on jackals and caracals. This final post in my 3-part blog series continues my narrative into the 1980s and explores some of the unintended consequences of predator extermination in Namibia, noting changes in how farmers and conservationists understood local ecological systems. I conclude the series with some brief thoughts on how historians can approach transformations in human-animal and human-environment relations.

In October 1966, farmers in Aroab, a small agricultural town in southeastern Namibia, faced a difficult situation: rodents and other small mammals had descended upon the district, eating the grasses and reducing the pasture condition to such a state that the district’s sheep were left with little to eat. Similar infestations were occurring throughout southern Namibia around this time; the main culprits were deemed to be dassies, Cape and scrub hares, and the Cape gerbil (known as nagmuise). The infestations sparked outcry from local conservationists, who argued that the rise in the number of ground mammals was linked to the wanton destruction of predators: over the previous 18 months, at least 22,242 jackals had been exterminated.

Conservationists did not appeal for an end to jackal killings, however. Instead, they asked for it to be done in a much more controlled manner, taking into consideration the ecological role of jackals and other animals classified as “vermin.” They noted that while it was necessary for farmers to eliminate certain carnivore offenders, large-scale eradication was unwise without increased understanding of the diets and ecologies of eliminated animals. For example, they noted that farmers had only recently realized that the aardwolf (maanhaarjakkals; Proteles cristata), which looked suspiciously like a jackal from a distance, was actually related to the hyena. Importantly, the aardwolf was 100 percent insectivorous, fed mostly on termites, and served a constructive role for farmers by eating insects that degraded fencing posts. Eliminating aardwolves because of surface-level similarities with predators could cause farmers more trouble than the cash bounty was worth, the conservationists argued.

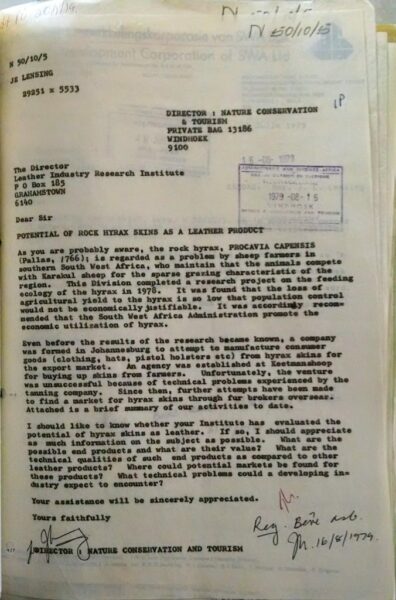

Correspondence from Johan Lensing, director of nature conservation at NTB, seeking information about using dassie pelts for leather production. National Archives of Namibia, NTB 2/274 File N.50/10/5: Navorsing Probleemdiere: Dassie Ekologie en Beheer (1976–1980)

Additional research and political pressures led the NTB to change vermin categories to reflect the purpose of control: profit. The NTB also came up with a more inclusive, yet ambiguous term “problem animal,” to define any species that caused “appreciable loss to the local agricultural economy” and whose numbers should be reduced. In other words, problem animals were creatures that got in the way of agricultural production, and the NTB reoriented its research to look at methods of controlling them. In the mid-1970s, Johan Lensing was brought on as the director of nature conservation at NTB and he made the “dassie plague” a major priority—farmers in the Karasberge complained that dassies were coming out from the rocks to graze on the veld, removing sparse quantities of pasture that karakul sheep needed.

Lensing quickly identified reasons for the growing dassie population, noting that for the past 10–15 years, farmers facing dassie problems had erected jackal-proof fencing and engaged in predator extermination campaigns. Lensing sought to temporarily control the dassie population using poisons such as telodrin, thallium, 1080 sodium fluoroacetate, and some antifertility agents, but in the end, he and other NTB ecologists advocated for restoring predator-prey relationships. These requests, however, fell on deaf ears as farmers, interested only in short-term goals, continued to eradicate jackals.

The dassie situation, however, was more complex and harder to manage, yet less serious than originally thought. On several farms in Karasburg and Keetmanshoop districts, Lensing examined stomach contents and found that, while it was true that dassies competed with sheep for grazing in dry seasons, they also utilized browse—high-growing vegetation—compared to the grasses preferred by the karakuls. Furthermore, dassies stayed near the outcroppings that provided them protection from birds of prey and jackals; therefore, the only grazing competition was near the rocks (poor grazing anyway). Finally, Lensing ran calculations on the economic cost of the dassie plague on affected farms and concluded that no more than 1 or 2 percent of profits were lost.

This is crucial because while farmers complained about all “problem animals,” they recognized that the jackal was the most serious. If a 3.5 percent predation rate could be negated with the caveat of a 1 percent loss through grazing competition with dassies, most farmers would take dassies over jackals any day. Furthermore, the actual process of eradicating dassies would have been maddening and incredibly labor intensive because the animals lived in outcroppings and not in burrows, making fumigation impossible. The only way to deal with dassies was to kill them manually with rifles and hounds, or to lay poisoned grain, which could harm livestock as well. Lensing’s team conducted research into the economic potential of hunting dassies for pelt production, but this ended after failed preliminary tests.

As few white farmers wished to re-engage the workers they had only just released, controlling these new “problem animals” would only be desirable if labor costs were low enough. At the end of the day, the karakul sheep was king, and dassies were thought to be an acceptable replacement for carnivores despite their long-term negative ecological effects. Among vermin, jackals were still the top dog.

Over the course of the 20th century, southern Namibia transformed completely. White farmers who’d entered the region several decades before with only a few dozen merino sheep became highly specialized fur producers, exporting over 3.4 million karakul pelts annually at their 1971 peak. Advances in breeding increased the fertility of their ewes and stud rams standardized and improved the quality of pelts. Bottlenecks were overcome, as fixed-capital investment into jackal-proof fencing and coyote getters reduced predation and slashed labor costs. Increased profits enabled faster turnover with many farmers participating in air freight service that brought pelts directly from the south to London’s auction houses.

But as Frederick Engels noted in 1872, capitalism rarely solves its constraints and bottlenecks, it merely shifts them elsewhere. This is why looking at rock hyraxes and similar small mammals is so important to understanding the economic and environmental history of Namibian agriculture. While technological innovation increased the profitability of sheep farms in the region, some of the increases in revenue were lost to dassies and overgrazing, leading to doubts about the long-term viability of intensive karakul sheep farming in arid southern Namibia. While jackals may eat a lamb, dassies and poor range management may starve it.

These fears came true with the near-collapse of the karakul industry in 1980–82, when the subcontinent was hit by one the strongest droughts of the century. With Namibian independence in 1990, it seemed that life would improve for the black population, but gains for farm workers have yet to be realized. Today, a number of white former sheep farmers in South Africa and Namibia have transformed their properties into game farms, seeking to tap into the biltong (game-meat jerky) and tourism markets, which have grown significantly in the post-apartheid years. Furthermore, labor reductions have continued; Brandt & Spierenburg have noted that game farms require far less labor than sheep farms. In many locales in southern Namibia, rural poverty and unemployment has increased since independence, and the purchasing power of the rand/Namibian dollar has decreased significantly.

As James C. McCann reminded us back in 1991, far too many studies of agriculture on the African continent engage with it only as a subfield of political economy, with little interest in agricultural technology, field systems, or range ecology. Historians of agriculture and rural capitalism must try to reveal the relationships between labor, markets, ecology, livestock, and wild animals. I hope that my (ongoing) work in southern Namibia is a small step in this direction.

This post first appeared on AHA Today.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.