In a 1995 interview with Linton Weeks of the Washington Post, [1] the Howard University librarian, collector, and self-described “bibliomaniac” Dorothy Porter (1905–95) reflected on the focus of her 43-year career: “The only rewarding thing for me is to bring to light information that no one knows. What’s the point of rehashing the same old thing?” For Porter, this mission involved not only collecting and preserving a wide range of materials related to the global Black experience, but also addressing how these works demanded new and specific qualitative and quantitative approaches in order to collect, assess, and catalog them.

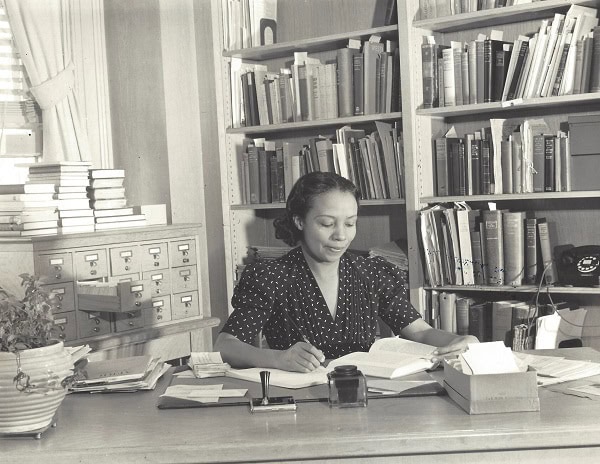

Dorothy Porter in 1939, at her desk in the Carnegie Library at Howard University. Moorland-Spingarn Research Center, Manuscript Division, Howard University

As some librarians today contemplate ways to decolonize libraries—for example, to make them less reflective of Eurocentric ways of organizing knowledge—it is instructive to look to Porter as a progenitor of the movement. Starting with little, she used her tenacious curiosity to build one of the world’s leading repositories for Black history and culture: Howard’s Moorland-Spingarn Research Center. But she also brought critical acumen to bear on the way the center’s materials were cataloged, rejecting commonly taught methods as too reflective of the way whites thought of the world.

Working without a large budget, Porter used unconventional means to build the research center. She developed relationships with other book lovers and remained alert to any opportunity to acquire material. As Porter told Avril Johnson Madison in an oral history interview, “I think one of the best things I could have done was to become friends with book dealers. . . . I had no money, but I became friendly with them. I got their catalogs, and I remember many of them giving me books, you see. I appealed to publishers, ‘We have no money, but will you give us this book?’” [2]

Porter’s network extended to Brazil, England, France, Mexico—anywhere that she or one of her friends, including Alain Locke, Rayford Logan, Dorothy Peterson, Langston Hughes, and Amy Spingarn, would travel. She also introduced to Howard leading figures like the historian Edison Carneiro of Brazil and pan-Africanist philosophers and statesmen Kwame Nkrumah and Eric Williams. As early as 1930, when she was appointed, Porter insisted that bringing Africana scholars and their works to campus was crucial not only to counter Eurocentric notions about Blacks but also because, as she told Madison, “at that time . . . students weren’t interested in their African heritage. They weren’t interested in Africa or the Caribbean. They were really more interested in being like the white person.” [3]

Porter developed relationships with other book lovers and remained alert to any opportunity to acquire material.

Howard’s initial collections, which focused mainly on slavery and abolitionism, were substantially expanded through the 1915 gift of over 3,000 items from the personal library of the Reverend Jesse E. Moorland, a Howard alumnus and secretary of the Washington, DC, branch of the YMCA. In 1946, the university acquired the private library of Arthur B. Spingarn, a lawyer and longtime chair of the NAACP’s legal committee, as well as a confirmed bibliophile. He was particularly interested in the global Black experience, and his collection included works by and about Black people in the Caribbean and South and Central America; rare materials in Latin from the early modern period; and works in Portuguese, Spanish, French, German, and many African languages, including Swahili, Kikuyu, Zulu, Yoruba, Vai, Ewe, Luganda, Ga, Sotho, Amharic, Hausa, Xhosa, and Luo. These two acquisitions formed the backbone of the Moorland-Spingarn collections.

Porter was concerned about assigning value to the materials she collected—their intellectual and political value, certainly, but also their monetary value, since at the time other libraries had no expertise in pricing works by Black authors. When Spingarn agreed to sell his collection to Howard, the university’s treasurer insisted that it be appraised externally. Since he did not want to rely on her assessment, Porter explained in her oral history, she turned to the Library of Congress’s appraiser. The appraiser took one look and said, “I cannot evaluate the collection. I do not know anything about black books. Will you write the report? . . . I’ll send it back to the treasurer.” The treasurer, thinking it the work of a white colleague, accepted it. [4]

This was not the only time that Porter had to create a work-around for a collection so as not to reimpose stereotyped ideas of Black culture and Black scholarship. As Thomas C. Battle writes in a 1988 essay on the history of the Moorland-Spingarn Research Center, [5] the breadth of the two collections showed the Howard librarians that “no American library had a suitable classification scheme for Black materials.” An “initial development of a satisfactory classification scheme,” writes Battle, was first undertaken by four women on the staff of the Howard University Library: Lula V. Allen, Edith Brown, Lula E. Conner, and Rosa C. Hershaw. The idea was to prioritize the scholarly and intellectual significance and coherence of materials that had been marginalized by Eurocentric conceptions of knowledge and knowledge production. These women paved the way for Dorothy Porter’s new system, which departed from the prevailing catalog classifications in important ways.

All of the libraries that Porter consulted for guidance relied on the Dewey Decimal Classification. “Now in [that] system, they had one number—326—that meant slavery, and they had one other number—325, as I recall it—that meant colonization,” she explained in her oral history. In many “white libraries,” she continued, “every book, whether it was a book of poems by James Weldon Johnson, who everyone knew was a black poet, went under 325. And that was stupid to me.”[6]

Instead of using the Dewey system, Porter classified works to highlight the foundational role of Black people in all subject areas.

Consequently, instead of using the Dewey system, Porter classified works by genre and author to highlight the foundational role of Black people in all subject areas, which she identified as art, anthropology, communications, demography, economics, education, geography, history, health, international relations, linguistics, literature, medicine, music, political science, sociology, sports, and religion.[7] This Africana approach to cataloging was very much in line with the priorities of the Harlem Renaissance, as described by Howard University professor Alain Locke in his period-defining essay of 1925, “Enter the New Negro.” Heralding the death of the “Old Negro” as an object of study and a problem for whites to manage, Locke proclaimed, “It is time to scrap the fictions, garret the bogeys and settle down to a realistic facing of facts.”[8] Scholarship from a Black perspective, Locke argued, would combat racist stereotypes and false narratives while celebrating the advent of Black self-representation in art and politics. Porter’s classification system challenged racism where it was produced by centering work by and about Black people within scholarly conversations around the world.

The multi-lingual Porter, furthermore, anticipated an important current direction in African American and African Diaspora studies: analyzing global circuits and historical entanglements and seeking to recover understudied archives throughout the world. In Porter’s spirit, this current work combats the effects of segmenting research on Black people along lines of nation and language, and it fights the gatekeeping function of many colonial archives. The results of Porter’s ambitions include rare and unusual items. The Howard music collections contain compositions by the likes of Antônio Carlos Gomes and José Mauricio Nunes Garcia of Brazil; Justin Elie of Haiti; Amadeo Roldán of Cuba; and Joseph Bologne, Chevalier de Saint-Georges of Guadeloupe. The linguistics subject area includes a character chart created by Thomas Narven Lewis, a Liberian medical doctor, who adapted the basic script of the Bassa language into one that could be accommodated by a printing machine. (This project threatened British authorities in Liberia, who had authorized only the English language to be taught in an attempt to quell anti-colonial activism.) Among the works available in African languages is the rare Otieno Jarieko, an illustrated book on sustainable agriculture by Barack H. Obama, father of the former US president.

Porter must be acknowledged for her efforts to address the marginalization of writing by and about Black people through her revision of the Dewey system as well as for her promotion of those writings though a collection at an institution dedicated to highlighting its value by showing the centrality of that knowledge to all fields. Porter’s groundbreaking work provides a crucial backdrop for the work of contemporary scholars who explore the aftereffects of the segregation of knowledge through projects that decolonize, repatriate, and redefine historical archives.

Notes

[1] “The Undimmed Light of Black History,” Washington Post, November 15, 1995.

[2] Dorothy Porter Oral History, Oral History Collection, Moorland-Spingarn Research Center, Howard University, 18.

[3] Ibid., 14.

[4] Ibid., 28.

[5]Library Quarterly 58, no. 2 (April 1988): 143–63.

[6] Dorothy Porter Oral History, 25.

[7] Glenn O. Phillips, “The Caribbean Collection at the Moorland-Spingarn Research Center, Howard University,” Latin American Research Review 15, no. 2 (1980): 162–78.

[8] Alain Locke, “Enter the New Negro,” Survey Graphic, March 1925.

Zita Cristina Nunes, associate professor of English and comparative literature at the University of Maryland, is the author of Cannibal Democracy and the principal investigator on a digital project on the Black press in Portuguese, supported by a three-year NEH grant.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.