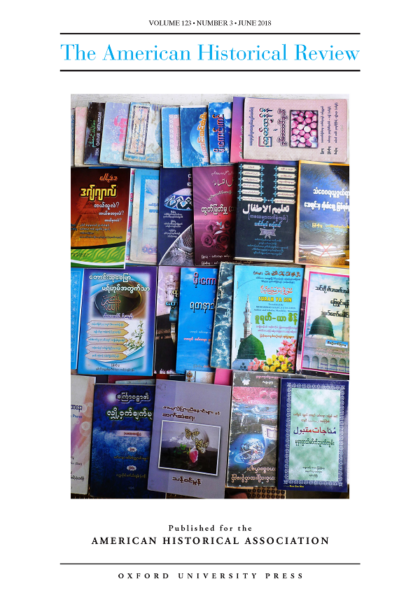

Muslim Books in the Multilingual Market of Ideas. Photo by Nile Green. The 19th century saw the birth, then massive growth, of vernacular language printing all around the Indian Ocean, particularly in pluralistic ports like Rangoon (today’s Yangon) that were the hubs of oceanic exchange. Yet despite the ascendance of Indian Ocean history over the past few decades, such sources remain woefully underexplored; they offer vital test cases for the much-vaunted cosmopolitanism of Indian Ocean societies. As Nile Green demonstrates in “The Waves of Heterotopia: Toward a Vernacular Intellectual History of the Indian Ocean,” such materials show that the intense interactions of the 19th century generated a more complex variety of attitudes than “cosmopolitanism,” suggesting in turn that the region may be better conceived through the model of “heterotopia”: a space for encountering difference. Read through this more capacious conceptual model, such vernacular materials equip researchers to respond to recent calls for the writing of global intellectual history in a way that recognizes both interconnections and regional distinctions. Green’s article is part of an AHR Forum titled “Vernacular Ways of Knowing,” which highlights methodological innovations used to uncover previously neglected histories.

In February and April 2009, the American Historical Review published a two-part forum, “The International 1968.” Is there anything new to say nearly 10 years later, to mark the half-century after that tumultuous moment in world history? While the six essays in that forum effectively captured the spirit of 1968, focusing on youth culture, popular mobilization in diverse forms, and the global impact of the counterculture, they were rather traditional in form. Yet the political and cultural epoch captured by the catch-all concept of “1968” was, above all, about experimentation, about a search for utopian ideals, about breaking the established rules—whether those rules came from an older generation, inadequate democratic processes, capitalist diktats, or sclerotic socialist or revolutionary regimes.

To that end, the forum on 1968—appearing under the heading “Reflections”—in the June 2018 issue of the AHR does break a few rules. First, there is the format, with which we took editorial license. When commissioning the 13 short essays (around 2,000 words each), I explicitly asked contributors to eschew scholarly intervention in favor of reflections examining the legacy and meaning of 1968 from the distance of a half century. That loose format and deliberately vague charge produced some traditional academic prose, but it also generated what one contributor called “politological meditations.” It allowed some personal contemplation, as well as an emphasis on the shifting meanings of 1968 over time—as more than one scholar has observed, the half-century mark is the twilight moment at which living memory begins to shade into archive-based history.

In addition to this unusual format, the essays create an unorthodox social geography of 1968. Yes, Prague and Paris and West Berlin, but also Warsaw and Turin and East Berlin. Not London, but Belfast. Mexico City, of course, but also places with less exact timing: China, Africa, the Arab world. Canada, rather than the United States. Not Columbia University, but the Left Coast, and the emergence there of Third Worldism and revolutionary black nationalism—with unanticipated results. As was the case in 2009, the burgeoning historiography of the “global sixties” has yet to settle on a comparative or transnational explanatory framework: Did events happen in synchronicity in 1968 because distinctive societies underwent similar experiences of post–World War II modernity and discontent, or were these local explosions set off by sparks leaping from place to place? Was 1968 a “moment” or, as one of the contributors puts it, a synecdoche for a whole host of decade-long transformations? It depends where one stands, and readers may be inspired to develop their own East-West, North-South, and even South-South comparisons. While these collective reflections cannot offer a definitive answer to these questions, my hope is that when read in conjunction with the 2009 forum, they will scatter many seeds for further contemplation and research.

The reflections on 1968 are followed by a far more regular feature, one of our serendipitous AHR Forums assembled from three articles submitted under separate cover. This one, “Vernacular Ways of Knowing,” showcases methodological innovations providing new insights into aspects of the past often regarded as largely unknowable. As Meso-Americanist Camilla Townsend (Rutgers Univ.) notes in her introduction to the forum, all three articles, with their common emphasis on language, both oral and written, return us to the original meaning of the vernacular—namely, the power of the mother tongue as an antidote against linguistic traditions imposed by others.

In “Bereft, Selfish, and Hungry: Greater Luhyia Concepts of the Poor in Precolonial East Africa,” Rhiannon Stephens (Columbia Univ.) draws on historical linguistics to reconstruct conceptualizations of poverty in precolonial East Africa. Her article explores how people speaking Greater Luhyia languages redefined what it meant to be poor as they settled new lands and interacted with other communities over time. The concept of poverty in this region, Stephens shows, gradually evolved from the economic insecurity implied by the loss of a household member to being associated with the selfishness and deceit practiced by those without resources to share with others. Through an analysis of the shifting geographic and chronological landscapes of language, Stephens highlights the dynamism in Greater Luhyian economic thought, tracing linguistic and thus conceptual change well before the advent of colonialism, Christianity, and capitalism in Africa.

James Pickett (Univ. of Pittsburgh) similarly recuperates lost voices in “Written into Submission: Reassessing Sovereignty through a Forgotten Eurasian Dynasty.” As he notes, the Central Asian city of Shahrisabz (in present-day Uzbekistan) has remained little more than a historical footnote, regarded merely as a thorn in the side of its more powerful neighbors during the 17th through late 19th centuries. In fact, Pickett shows, Shahrisabz was an autonomous city-state in its own right. The mechanisms obscuring this city’s past reveal much about historical methodology and premodern logics of sovereignty. To recover Shahrisabz’s story, Pickett revisits Persian texts that dominate historical knowledge of this region, piecing together scattered fragments composed within the city itself. In doing so, he illustrates how seemingly contradictory forms of sovereignty routinely coexisted within a single polity. In Pickett’s account, approaches to sources and concepts of sovereignty stand as two domains intrinsically intertwined, with insights into the latter possible only with careful attention to the language and logics embedded in the former.

Finally, in “The Waves of Heterotopia: Toward a Vernacular Intellectual History of the Indian Ocean,” Nile Green (Univ. of California, Los Angeles) focuses on this polyglot region’s diverse vernacular spheres of writing that rapidly widened in the era of print. Green contends that the characterization of the colonial-era Indian Ocean as an arena of “cosmopolitanism” proves a poor fit with the variety of intellectual transactions evident across so heterogeneous a space. By widening his conceptual apparatus across multiple print traditions, Green challenges the premise that oceanic actors operated under the intellectual hegemony of a “colonial episteme.” Overall, his essay argues for understanding the 19th-century Indian Ocean through an alternative conceptual framework of “vernacularism” and “heterotopia” that allows for the multiple intellectual trajectories of such world-historical contact zones.

The June issue also contains another entry in our ongoing “Reappraisals” series. This one features anthropologist Eric Wolf’s Europe and the People without History (1982), one of the first major texts to insist that societies and cultures outside the orbit of what came to be called Europe were equal partners in the making of modernity. Pekka Hämäläinen offers a reconsideration of Wolf’s foundational work in forcing a rethink of “core and periphery” in world history, emphasizing subsequent development in indigenous history.

Collectively, the article revisiting Wolf’s classic, the forum on new ways of thinking about neglected sources and the vernacular, and the effort to allow multiple voices to speak about 1968 reflect the ongoing efforts of the AHR to attend to the exciting multiplicity of approaches to the past that now define the historical discipline. A forthcoming initiative, called “History Unclassified,” will soon add new forms of historical writing to this endeavor. Please join us in continuing to break the rules.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.