Messaging from the Oval Office, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and state and local public health agencies on COVID-19 has been mixed, to say the least. Misinformation abounds, ranging from shifting messages about masks and the use of different drugs against COVID-19 to President Donald Trump’s speculations about injecting coronavirus patients with disinfectants. Unfortunately, conflicting statements like these, along with the lack of reliable, consistent public health information, has caused confusion and fueled the spread of misinformation in the US.

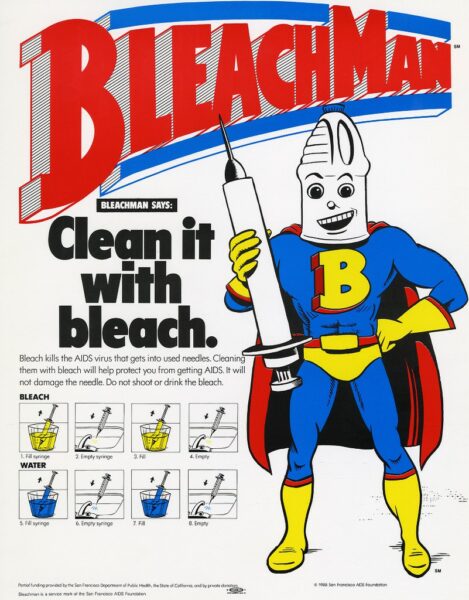

BleachMan meets the public at his first appearance in San Francisco. Courtesy of UCSF Archives and Special Collections. BleachMan at his first public appearance, San Francisco AIDS Foundation, 1988, San Francisco AIDS Foundation Records, MSS 94-60, carton 25.

In the 1980s, a similar struggle to provide coordinated, accurate public health information emerged with the rise of HIV and AIDS. The national response to this crisis lagged. Ideas about “traditional family values” and prejudices about homosexuality led to President Ronald Reagan’s delayed acknowledgment of AIDS (he didn’t mention the disease in public until 1985) and his stalling early funding for research and treatment for a disease called the “gay cancer” or the “gay plague” in early days. This political and moral posturing cultivated fear and interfered with the development of national communication campaigns about HIV/AIDS.

We can draw parallels between the inaction of the federal government and the CDC in both the HIV/AIDS and COVID-19 epidemics. Grassroots attempts to spread information about HIV/AIDS filled the large gaps left by the federal government and the CDC. Because of its high transmission rates, San Francisco became a key location for HIV/AIDS research and educational outreach. The swift response of San Francisco grassroots organizations in educating the public about HIV/AIDS can provide valuable lessons in how local organizations might offer uniform and factual information about COVID-19 that may save lives in the absence of clear and effective federal leadership today.

The first US cases of HIV/AIDS emerged in 1981, and San Francisco AIDS organizations worked quickly to provide educational materials about the transmission and prevention of the disease. Community leaders and physicians founded the San Francisco AIDS Foundation (SFAF) in April 1982. From its phone hotline to pamphlets about safe sex practices, the SFAF became a national leader in informing the public on research about this new virus.

We can draw parallels between the inaction of the federal government and the CDC in both the HIV/AIDS and COVID-19 epidemics.

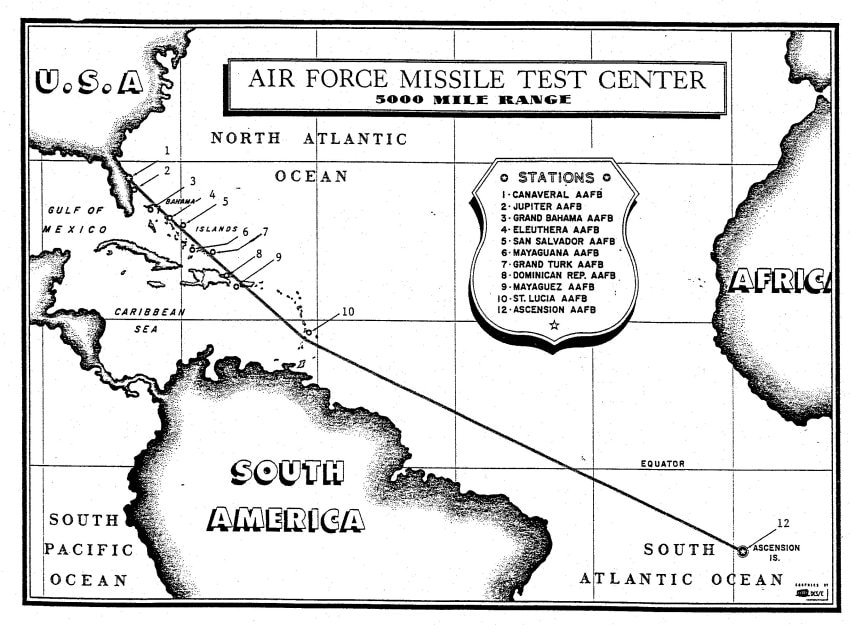

In an effort to reach people who used intravenous (IV) drugs, among whom HIV rates were rapidly rising, SFAF developed BleachMan in 1987. The illustrated BleachMan character appeared in newspaper ads and educational comic books, explaining the importance of cleaning injection supplies and teaching the process to readers. “Clean it with bleach,” he urged San Franciscans on billboards, TV commercials, and T-shirts. An eight-foot-tall BleachMan mascot attended street fairs, media events, drug treatment programs, and international conferences. He distributed condoms and bleach, and used his four-foot-long display syringe to demonstrate cleaning needles with bleach.

By December 1988, after just a year, the BleachMan campaign and the SFAF’s other drug outreach efforts had convinced up to 80 percent of the city’s IV drug users to disinfect their needles. Their success illustrates how innovative ad campaigns like this could reach audiences on the city’s streets and extend awareness of harm-reduction practices. Although San Francisco politicians may not have publicly backed this program, nobody prevented BleachMan from educating drug users and distributing clean needles, condoms, or “Clean It with Bleach” T-shirts.

Although San Francisco led the way in creative approaches to educating the public about HIV/AIDS, not all cities were so quick to follow their lead. Opponents argued BleachMan condoned drug use and violated laws criminalizing drug paraphernalia distribution. Politicians in other cities, such as Los Angeles, blocked BleachMan copycat plans and needle exchange programs. Similar HIV/AIDS education and outreach varied dramatically across the US.

In San Francisco, local organizations and volunteers did the bulk of this educational work in the absence of a federal government that valued scientific research.

In San Francisco, local organizations and volunteers did the bulk of this educational work in the absence of a federal government that valued scientific research. This approach often focused attention on mostly white gay men, leaving out impacted populations such as communities of color and IV drug users. However, by modifying its outreach to target a variety of audiences, BleachMan brilliantly provided educational outreach and resources to different at-risk communities often ignored during the HIV/AIDS crisis.

Today, there are similar conflicts during the COVID-19 pandemic. Local organizations, state and city governments, and, at times, the CDC are providing public health advice about COVID-19. But larger national public health education seems spotty and uncoordinated at best.

In the absence of coordinated public health guidance, what can we learn from BleachMan? The SFAF accounted for local needs both in the content and communication methods of the BleachMan campaign. They identified dirty needles as a common avenue for HIV transmission and that they needed multiple approaches to reach this audience. Educational materials, billboards, and getting out on the streets with BleachMan reached these at-risk populations and helped provide science-backed remedies to help prevent disease transmission. BleachMan extended the reach of SFAF by including different at-risk populations, which added to its larger programs of outreach and HIV/AIDS education.

A 1988 BleachMan advertisement created by the San Francisco AIDS Foundation. Courtesy of UCSF Archives and Special Collections. BleachMan poster, San Francisco AIDS Foundation, 1988, AIDS History Project Ephemera Collection, MSS 2000-31.

With the closure of public spaces throughout the spring of COVID-19, a giant MaskMan walking around may not be effective in preventing transmission. But analyses of local needs and agreement on coherent mitigation procedures provide an important start. To ensure the effectiveness of our social distancing efforts, it’s key to convince the public of the importance of harm-reducing and mitigation tactics, like wearing masks in public and maintaining social distancing, even if new case numbers plateau. Viewing our leaders modeling preventative behaviors such as wearing masks and keeping six feet apart during press conferences and local appearances can also provide a good start.

The American public needs cohesive, evidence-based public health information about COVID-19—and we need it soon. Through nationally coordinated efforts, as well as through local grassroots efforts, the US can educate residents to protect their health and those who live around them while we wait for an approved vaccine or symptom mitigation.

Lindsey Passenger Wieck is the public history graduate program director and assistant professor of history at St. Mary’s University. She tweets @LWieck.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.