Summer has arrived! The school year has ended. The weather is warmer. The days are longer. And for many graduate students in their second through fourth years, summer offers more time to read for history oral exams. As someone who has successfully survived a year packed to the brim with books, I can assure you that the anticipation is much worse than the process. Here are a few strategies that I used to get through the reading process in one piece! [Note: Each university varies in regards to the exact parameters of exams. The history department at Columbia, for instance, does not require graduate students to sit for written exams. After chatting with others who have gone through different versions of this process, the following list is an amalgamation of advice that I found useful and incorporated into my own studying.]

1. Choose books you actually want to read.

When formulating your lists with your field examiners, be sure to include books that you actually want to read. Sure, it’s important to understand the historiography of a given subject and to familiarize yourself with the foundational texts in your field. But it’s also important that you take the opportunity to read widely and deeply about topics that interest you and that might come to inform your future teaching or dissertation writing.

Plus, having books on the list to look forward to will help make the dull books less arduous.

2. It’s okay to read only the introduction, conclusion, and the book review.

In fact, it’s the only way to keep on schedule and avoid pulling your hair out in the process. Be strategic about which books you read in full and which books can be downgraded to the intro/conclusion/review-only pile (Sorry, Carl Bridenbaugh’s Cities in the Wilderness…). It’s simply not possible to read every single word on every single page—and that’s okay!

3. Get cozy with your calendar.

There’s nothing worse than sitting down to tackle a reading list and finding yourself unsure of where to start. It’s time to pull out your calendar and do a little bit of math. Once I finalized my lists, I mapped out a schedule that included a reading start and end date for each list, a review period, and a desired exam date. Then I tallied up the total number of books on my lists and calculated how many I needed to read per day to reach these goals (approximately two and a half books per day from June 1 to November 1, with about three weeks of review before Thanksgiving, and a mid-December exam date).

Figure 2: Though empty reading rooms are a rare occurrence in Columbia’s Butler Library, they are a good reminder not to become a hermit while reading for exams. (Photo by author)

4. Stop reading!

Once you establish a schedule for yourself, it becomes much easier to allow yourself to stop reading. Your schedule gives you permission to go off the clock when the workday is done. You shouldn’t be reading 24/7. Take breaks. Don’t work (or at least work less) on weekends. This means that if you make it to the end of the day and you haven’t finished a book then it’s time to move on. Remember, the “review” period is already on the calendar if you need to spend more time with a book.

5. Remind yourself that you are not a hermit.

Whether it’s a fellow grad student or sympathetic friend, it can be helpful to have a person to talk to about the material or to decompress with at the end of a long book-filled day. Orals reading does not need to be a solitary process. You might even find that talking about books helps with review; you’ll be better equipped to remember material once you’ve summarized it in your own words.

6. Find a review strategy that works for you.

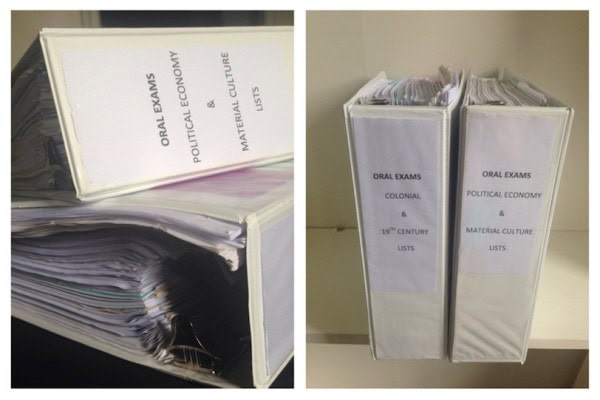

One thing’s for sure, the oral exam process requires you to synthesize and recall a great deal of information—often months after you read the book. Whether writing notes, keeping reading lists on your computer, composing review essays, or making flash cards, it’s helpful to maintain a review system throughout. I kept large three-ring binders full of materials that included book reviews, articles, and then my own one- to two-page summary of each book. Each summary addressed the book’s central question, argument, relationship to larger historiography/field, and key source materials. I analyzed the book’s strengths and weaknesses and recounted one to two brief anecdotes or stories from favorite chapters. I also studied with a textbook and on the phone with “history-minded” friends in the weeks immediately before the exam. These binders and conversations were great for jogging my memory and boosting my confidence as the exam date drew closer.

Figure 3: These two binders, filled with notes, articles, and book reviews were extremely helpful during review (and took up much less space than shelves of books!) (Photo by author)

7. Accept that it’s simply not possible to know everything.

I think most graduate students who have completed the exam process would agree that the exam is about breadth of knowledge, and not necessarily the minute details of a specific book and page number. If you’re worried that you might not know which information is the most essential, it can be helpful to ask your field examiners what is expected of you in the exam. For instance, one of my examiners did not want me to “name drop” books; he was more interested in my ability to synthesize and explain how changes over time influenced certain events, people, and ideologies. Another examiner stressed the importance of recalling population figures, dates, and the specifics of certain events. Furthermore, each topical list required knowing a different set of information. Once I knew what was expected, though, I could study accordingly.

8. Celebrate!

There will come a day when the books will be read, the knowledge will be shared, the examiners will be pleased, and you, Dear Reader, will have PASSED! Celebrate that accomplishment, revel in that mastery, and pat yourself on the back for an arduous job well done.

Comprehensive exams are a rite of passage for history PhD students. For more advice, read tips from the AHA’s Graduate and Early Career Committee. AHA members also have free access to Choice Reviews Online, featuring over 7,000 reviews of new scholarly books. This is a great resource when you’re studying for comps. Log on to MY AHA to access this benefit.

Share your own tips in the comments below or on Twitter or Facebook.

This post first appeared on AHA Today.

Katy Lasdow is a PhD candidate in early American history at Columbia University and the assistant public historian at the Brooklyn Historical Association. Her dissertation is entitled “Spirit of Improvement: Construction, Conflict, and Community in Early-National Port Cities.” Katy passed her oral exams with distinction in December 2014.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.