We offer these pieces with a few caveats. Much of what can be done quickly is not properly online instruction(courses envisioned for online or hybrid execution). Rather, for many, this is a rapid transition to remote instruction. Similarly, much of the advice depends on your own institutional circumstances; with regard to policy, particularly ADA policy, always defer to the rules of your home institution. Still, we hope these posts will help support student learning during these turbulent times, and we invite discussion of them and an exchange of ideas—both broadly conceived and narrowly practical—on the AHA Members’ Forum.

Like many of you, I will be moving my face-to-face courses to an online platform for the remainder of the semester. This method is not new to me: I have taught online courses for the last 10 years and have a few tips that might help those now settling into remote teaching, particularly ideas for communicating with and assessing students as we move through these last few weeks of the semester.

Lean Forward/Flickr/CC BY-SA 2.0

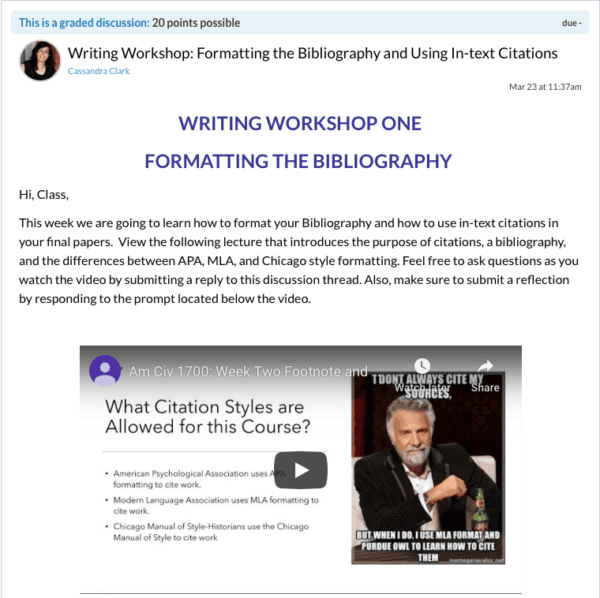

In remote teaching, assessment takes on a different purpose. Assignments allow us to teach important concepts and track student progress. My first objective for the transition to remote learning is to ensure that students understand the content of the recorded lectures. Because students tend to stop watching course videos that last longer than 10 minutes, I’ll break the lectures into mini-presentations and embed them into separate Canvas discussion posts. Underneath each lecture video, I’ll post graded questions and reflection prompts that relate to the video content. Clear and detailed rubrics are essential to effective discussion threads: designing a rubric with separate categories for content, analysis, format, and grammar/word count lend structure to student interactions with each other and with their instructor. Assigning grades will help me to determine both who is watching the material and to clarify my ideas and respond to theirs.

The next objective is to transfer all assignments online. In the US history survey, I assign a semester-long research project. So far this term, students have chosen their topics, learned how to search for primary and secondary sources, practiced analyzing both, and turned in a list of sources they will use to complete their projects. Next, they will submit a bibliography. Since I am unable to conduct the in-class writing workshop from the classroom as planned, I have recorded a video to demonstrate how to format a bibliography and footnotes. I added graded discussion prompts that encourage students to ask questions and share what they learned in order to simulate a classroom environment, and will upload a sample bibliography to the module for visual learners. The assignment rubric will cover formatting expectations and stipulate the minimum number of sources. The activity looks like this:

-600x464.png) As institutions transition to online instruction in the face of COVID-19, historians are struggling with what it means to teach history online. The AHA had planned to announce guidelines in June 2020 for online teaching in history, and we will continue to work to do so. In the meantime, we are publishing a series of short pieces in Perspectives Daily to help the many historians now working to navigate this emergency.

As institutions transition to online instruction in the face of COVID-19, historians are struggling with what it means to teach history online. The AHA had planned to announce guidelines in June 2020 for online teaching in history, and we will continue to work to do so. In the meantime, we are publishing a series of short pieces in Perspectives Daily to help the many historians now working to navigate this emergency.

Lecture-based discussion prompts are not the only assessment tool for tracking students’ comprehension and retention of course materials. Discussion prompts (one- or two-paragraph responses to a question about a reading or topic) and engagement prompts (a student’s reply to another student’s response) designed to enhance critical thinking skills are also effective online learning resources. A rubric with prompts can clearly outline course expectations, including a word limit for all student posts, due dates, and the quality of evidence required to support their answers. Discussion and engagement posts have different due dates. In this case, the initial post is due by 11:59 p.m. on Thursday of a discussion week and the two engagement posts are due no later than 11:59 p.m. on Sunday of the same week. Discussion/engagement activities offer students space to think critically about a topic while also providing them with the opportunity to improve their written communication skills.

Positive and supportive feedback is particularly essential to online instruction. Remember, from this point forward, your students will engage with you only within the limits of a digital realm. This means that their impression of you is based entirely on the way you communicate with them online. Short, disapproving comments added to a paper—“this is unclear,” “passive voice,” or “rewrite this paragraph”—are less helpful than something like: “I can tell you have the right idea in this paper, but grammatical mistakes and organizational issues make it difficult for me to follow your thoughts. Please review my comments, rewatch the instructional video, and complete a new draft within the next seven days to ensure you meet the assignment objectives and earn a grade worthy of the work you’ve done here. Do not hesitate to send me a working draft of your revised essay before you submit. I am happy to help.”

Finally, getting certain details right can improve student learning outcomes: make sure your instructions and rubrics are clear, that your links work, that you provide contact information for your school’s technical support, and that you grade work often.

Cassandra L. Clark graduates with her PhD from the University of Utah this spring, and is an adjunct instructor at Salt Lake Community College and a member of the AHA’s ad hoc committee on online teaching. She tweets @cassiel_clark and can be reached at Cassandra.clark@utah.edu with questions about teaching online.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.