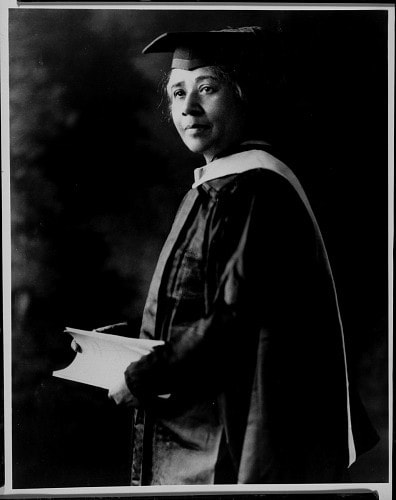

Anna Julia Cooper. Scurlock Studio Records, Archives Center, National Museum of American History. Smithsonian Institution.

One of the most prominent intellectuals and courageous educators of her time, Anna Julia Cooper was an outspoken advocate for racial and gender equality. Most well known for A Voice from the South by a Black Woman of the South (1892), in which she theorized intersecting forms of oppression and advocated for a broad and inclusive approach to liberation and human rights, Cooper was also likely the first Black woman from the United States to earn a PhD with a dissertation in history. Now recognized as a foremother of Black feminist thought and intersectionality and a forerunner in the fight for Black education, Cooper was forced by prejudice to take a circuitous route to secure education for herself and others.

Born into slavery in Raleigh, North Carolina, on August 10, 1858, Anna Julia Haywood Cooper was the youngest of three children born to Hannah Stanley Haywood and presumably her enslaver, George Washington Haywood. In 1867, Cooper entered the first class of Raleigh’s St. Augustine’s Normal and Collegiate Institute, where she went on to be a teacher. From there, she launched her first protests for equal rights, including calling for state support for Black education. She was married to George A. C. Cooper from 1877 until his death in 1879. Cooper then attended Oberlin College, where she earned BA (1884) and MA (1888) degrees in mathematics.

From the mid-1880s through the turn of the 20th century, as white politicians and publics abandoned Reconstruction reforms, Cooper published widely and delivered speeches across the nation and the world, arguing against the revisionist histories of Reconstruction taking shape and advocating for Black rights and equality. In 1887, she moved to Washington, DC, where she helped found institutions including the Colored Women’s League, the Phyllis Wheatley YWCA, and the Colored Settlement House. In 1896, she worked with other prominent women to found the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs, uniting hundreds of local and state groups and moving Black women unapologetically to the forefront of their own national organizing efforts.

In 1901, she was appointed principal of the prestigious Washington Colored High School, known as M Street and later Dunbar High School, where she headed a rigorous classical and liberal arts program and succeeded in sending Black students to elite colleges and universities. Her success, however, brought her face-to-face with bitter local, regional, and national politics, and in 1906, her “courageous revolt” against a “lower colored curriculum” led to her removal as principal, though she would later return to the teaching staff.

Immediately after her removal, Cooper initiated efforts to pursue a PhD, but she was repeatedly thwarted, delayed, and rerouted by limited opportunities, lack of support and resources, and requirements unforgiving for a single Black woman raising five adopted children. In 1914, Cooper enrolled at Columbia University and completed a scholarly translation of Le Pèlerinage de Charlemagne as her doctoral thesis. Unable to meet the program’s residency requirements, however, Cooper would not earn her PhD until 1925, from the University of Paris, Sorbonne, only the fourth African American woman to earn a PhD and the first to do so with a historical study. Her dissertation, L’Attitude de la France à l’égard de l’esclavage pendant la Révolution, is a deeply archival historical study situating the French Revolution in the context of the transatlantic slave trade and reconstructing the history and dialectical relationships between the French and Haitian Revolutions.

Cooper taught at Dunbar High School until her age-mandated retirement in 1930. After her retirement, she continued to write, edit, and teach, contributing at least 28 articles to local newspapers and privately printing a two-volume collection of writing by and about fellow educator and activist Charlotte Forten Grimké. In 1930, she became president of Frelinghuysen University, a group of community schools that served the working Black adults of Washington, DC. Throughout her life, she remained steadfast in her faith in education as a vehicle for individual and social transformation and unmoved in her critique of systems of oppression and domination that diminished the freedom and life chances of African Americans generally and Black women specifically.

Cooper died on February 27, 1964, at her home in the LeDroit Park neighborhood of Washington, DC. She was 105 years old. Fellow Dunbar graduate Mary Gibson Hundley remembered Cooper as “a woman of rare courage and conviction.”

Shirley Moody-Turner

Penn State University

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.