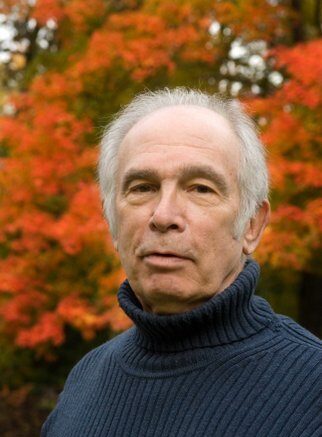

James M. Banner, Jr., is a retired historian. He lives in Washington, DC, and has been a member since 1960.

Beverly Reznick

Social Media: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_M._Banner_Jr.

Alma maters: BA, Yale University, 1957; PhD, Columbia University, 1968

Fields of interest: early American Republic 1765–1865, discipline of history, historical thought

Describe your career path. What led you to where you are today?

I entered graduate school in 1960 with the intention of becoming an academic historian, a goal I achieved when appointed instructor in the Princeton history department in 1966. After gaining tenure, I remained a member of that department until resigning my professorship in 1980. Some thought that rather than taking leave of that extraordinary faculty, I had instead taken permanent leave of my own faculties. I have never thought so.

The reasons I left were two. First, after six years of service, including years of the Watergate Crisis, on the national governing board of Common Cause, the “citizens’ lobby” founded by John W. Gardner, I had gained experience and satisfaction in helping govern a general membership organization. Second, increasingly concerned about the growing troubles facing the humanities in the United States, my colleague Theodore K. Rabb and I in 1979 founded the American Association for the Advancement of the Humanities. It gathered steam until the economic recession during the Reagan administration and the inherent difficulties of gathering scholars in the humanities disciplines into a common enterprise made its continuance untenable. With academic positions beginning their decline, I became what we now call a “public historian.”

To make a living, I assumed posts at a research institute as its director of publications and at a federal foundation as its academic director. But I remained a historian, continued to teach part-time, to write and do history, and to participate in professional affairs. Was I an academic historian? Maybe not, but I certainly felt and acted like one. A public historian? Perhaps yes; after all, I wasn’t a faculty member. But what, really, was I? “A historian,” I’ve always said, the only suitable honorific for whatever we may do and for whatever purposes we may do it.

How have your historical interests evolved across your career?

I’ve always been a historian of the United States, 1765–1865. But that proved too confining. Interested and involved in many institutions, I’ve written and taught about the discipline of history and most recently about historical thought. Taking cues from my own life, I’ve written about teaching and learning, about presidential misconduct, and, because of a conversation some years ago with Justice Clarence Thomas, about revisionist history.

What projects are you currently working on?

I’m writing a book about historians—who we are, what we do, and why we do it.

What’s the most fascinating thing you’ve ever found at the archives or while doing research?

Too late for inclusion in my first book, I found a collection of documents, the first known, containing tabulations of the funds raised and the methods used to raise funds for Federalist election campaigns in Massachusetts in the early 19th century.

Who in your life served as a teacher or mentor and influenced your understanding of history?

Too many to name—not all of them historians. The three most important: Winton U. Solberg at Yale, Richard Hofstadter and Eric L. McKitrick at Columbia.

What do you value most about the history discipline and community?

Its success in containing multitudes—of different people, minds, dispositions, interests, and commitments.

Do you have a favorite experience with the AHA?

My first annual meeting, a year after I’d joined the AHA. The setting: The Shoreham Hotel, Washington DC, late December 1961, 9:00 a.m. Opening session. Subject: the Populist movement. Dramatis personae: Stanley Parsons, a solid paper on Nebraska populism; Norman Pollack on the Populist response to industrialism. Pollack may have delivered a paper of exceptional learning and interpretive power. But who could tell? Crushing 40 minutes of text into 20, he spoke his words at a speed greater than the rate of the machine guns I’d fired in military service. Two commentators. Open discussion. But not a word about Populism below the Mason-Dixon Line, nor about Pollack’s incomprehensible paper. Was this how historians acted? Then the final scene. Moderator C. Vann Woodward rises to end the session. Not wanting the opportunity to slip away, in his soft, southern-inflected voice and with the sly wit I later came to know well, Vann utters only four words before adjourning the session: “What about the South?” The room erupts in knowing laughter. I have received my AHA baptism. My relationship with the organization, now 65 years long, has begun.

If you have served on the AHA Council, a committee, or an AHR advisory board, what has been your favorite part of that experience?

As one of two historians who proposed what became the AHA Review Board of the early 1970s, I found deeply satisfying my work under the chairmanship of Hanna H. Gray to draft and see adopted a new AHA constitution, the one under which the AHA continues to be governed.

AHA members are involved in all fields of history, with wide-ranging specializations, interests, and areas of employment. To recognize our talented and eclectic membership, Perspectives Daily features a regular AHA Member Spotlight series.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.