In August 2012, two friends and I started a small college program at the Indiana Women’s Prison (IWP), which historians consider to be the first women’s prison in the nation. Over two years, our program grew to 15 teachers and 80 students. Although many of our students need remedial help, some are truly outstanding, and nearly all are highly motivated. Our faculty members are mostly retired professors from some of central Indiana’s best universities. For example, John Dittmer, a retired historian from DePauw University, teaches two of our most popular courses—on the US civil rights movement, and the United States in the 1960s.

A major challenge for college faculty in prisons is finding a way to teach students how to do research when they have no access to the Internet and virtually none to books and articles. I knew that our prison and the Indiana State Archives had reams of original documents about the prison dating back to its founding in 1873. Thus, I set out to teach our best students how to do research by writing a history of the prison—in one semester. Four semesters later we are still at it. Along the way, our initially happy tale of two noble Quaker women who rescued their sisters from a brutal male prison and founded the nation’s first women’s prison has taken many dark and surprising turns, some of which are noted in the accompanying article by Michelle Jones. In the process, the students have begun to present their research at academic conferences via videoconferencing and to publish their findings, a process that I expect will continue for at least four more semesters.

I am not a historian, but I am no stranger to prisons and prison history. After graduating from college, I worked as a prison officer at the Connecticut State Prison for Women, and I later went to graduate school at Harvard, where I wrote Prison Officers and Their World (1988). The book includes a long chapter on the history of the Massachusetts prison system. Since then I have maintained a keen interest in prison history, including the Indiana Women’s Prison, which is how I knew of the documents and various accounts by historians about that prison.

It was not until we were well into our history project at IWP that I realized that historians and I had been asking the wrong questions about the prison. My students, on the other hand, have consistently asked the right questions—often-cynical, penetrating, exacting ones that not only have exposed new information about the founders of this prison, but have challenged prevailing ideas about where, when, and by whom prisons for women were started and, most importantly, why. Jones’s article discusses some of their key findings.

This is not the first time that I have come to realize how valuable my prison students’ insights are and what we miss by excluding their voices. One of the courses we teach at IWP is Public Policy; in it the students learn standard information about state and local governments and how to analyze existing policies and advocate effectively for new ones. Then they turn their attention to bills before the Indiana state legislature on which they have genuine expertise—prisons and the criminal code, of course, but also poverty, sexual assault, drugs, and mental illness. After careful analysis and much debate, they write testimony on these bills that others present on their behalf before House and Senate committees. (For example, our students were the first to bring to the attention of the legislature that none of the nearly 30,000 people in Indiana prisons is currently diagnosed as having autism, and that some behaviors that are construed as oppositional by prison staff may be due to autism instead.) So useful and constructive have their insights been that Indiana state legislators of both parties regularly come to the prison to discuss these issues with our students.

Not only do people in prison make highly motivated, often strikingly original students, research shows that attending college while in prison also substantially improves recidivism rates.1 Another benefit is that college programs change prison environments by giving hope and meaning to those who are enrolled, as well as to those who aspire to be enrolled.

Yet college programs exist in only a small fraction of prisons in the United States. Many more programs existed before Congress passed the Omnibus Crime Bill of 1994, which included a ban on Pell Grants to people in prison. The United States had already begun its mad rush to incarcerate people—especially people of color—that would increase the number of state and federal prisoners seven-fold in 30 years. Indiana was one of the few states that maintained college programs using state funding, and it soon had perhaps the best and most extensive prison college program in the nation. Ten percent of all men in prison in Indiana were enrolled full-time and 15 percent of women. Then, in 2011, abruptly and without debate, the legislature withdrew all funding. College programs in all but one of the state’s prisons collapsed almost overnight as colleges and universities—public and private—quickly withdrew not only their instructors but also their books, computers, and supplies. The thousands of men and women who had been enrolled in those programs were, of course, deeply disappointed; so too were many of those who worked in Indiana’s prisons. When we approached the Indiana Department of Correction and the Women’s Prison a few months later with the idea of restarting the college program at IWP with an all-volunteer faculty and at no cost to the state, we were welcomed with open arms.

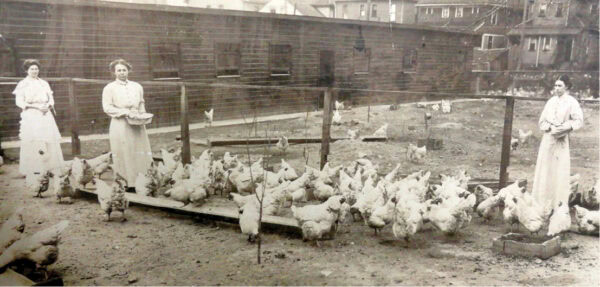

Women feeding chickens at the Indiana Women’s Prison.

The only problem was finding a private college that would partner with us. We would spend no money, but we would also generate none. Plus, there was the prickly problem of giving college degrees to prisoners—not good for the college brand. Finally, a small private college with a mission close to our own agreed to be our degree-granting institution, only to have to withdraw 18 months later for reasons unconnected to our program. We have now spent nearly a year searching for another Indiana college to take us on, with no luck. Thus, we find ourselves a thriving college program with wonderful students, strong faculty, great courses, supportive administration, no cost—and no college.

It has been a frustrating quest, yes, but in the process we’ve learned the essential lesson that the problem isn’t Indiana’s alone. Colleges and universities, in general, are loath to provide credit and degrees to prisoners. Of the prison college programs that exist, far too many allow “inside” and “outside” students to take courses together or in parallel, yet they grant credit only to the “outside” students, a model that I think is unfair and perhaps exploitative. A few colleges—most notably Bard—do grant degrees, but those programs tend to be highly selective and take few students. We have too many “gems in the rough” at our prison to pass up the opportunity to educate as many people as we possibly can.

I don’t know what the solutions are—one might be consortiums of colleges to grant credit and degrees to people in qualified prison programs—but we need to find or create them soon. Prisons in the United States are, as Michelle Alexander observes, the “new Jim Crow” and have done much to destroy what the civil rights movement gained, to say nothing of efforts to lessen poverty in this nation.2 Yet, ironically, prisons today offer an extraordinary opportunity to provide quality higher education to historically marginalized groups of all colors if only we will seize it. So far, we have not.

I would like to end with two invitations. The first is to retired historians and other researchers. As Michelle Jones notes in her article, one of the greatest frustrations that my students in the prison history project experience is how long it takes me to respond to their many requests for information. I need help tracking down myriad leads on such topics as Sarah Smith’s roots in England; the history of the Magdalene laundry in Buffalo, New York; 19th-century sewage systems; and the incidence of female circumcision in the 1870s. We would be delighted and grateful to have your help.

The second invitation is to historians in the Indianapolis area to teach in our program. The courses we offer are those that our volunteer faculty members want to teach. Thus, math has become our top subject for the simple reason that we have four excellent math teachers willing to teach every semester. (Next semester we will have eight women taking calculus—not bad for a female population whose median age is the late 30s.) Between John Dittmer’s seminars and the prison research project, our advanced students have had excellent opportunities to study and research history. But we don’t currently offer any 100- or 200-level history courses even though our beginning students are keenly interested in taking those courses.

If you are interested in volunteering, please contact me at kelsey.kauffman@gmail.com.

is the volunteer director of the Higher Education Program at the Indiana Women’s Prison and also teaches in the program. She has worked as a prison officer and has taught in three prisons. Her research, which has taken her to more than 80 prisons on four continents, focuses primarily on the impact prison employment has on officers, problems of white supremacy among prison employees, and mothers in prison.

Notes

1. Wendy Erisman and Jeanne Bayer Contardo, “Learning to Reduce Recidivism,” Institute for Higher Education Policy, November 2005, https://www.ihep.org/sites/default/files/uploads/docs/pubs/learningreducerecidivism.pdf.

2. Michelle Alexander, The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness (New York: New Press, 2010).

The American Historical Association welcomes comments in the discussion area below, at AHA Communities, and in letters to the editor. Please read our commenting and letters policy before submitting.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.