My mother, Mary Elizabeth Lunny Norton, died this past August, about a month before her 105th birthday. For years in my women’s history course I used episodes from her life to illustrate aspects of modern American women’s lives. I think it appropriate that I recount her life story in my final column as president of the American Historical Association, because our lives as professional women were both similar and dissimilar, in ways that illuminate recent changes in American women’s experiences.

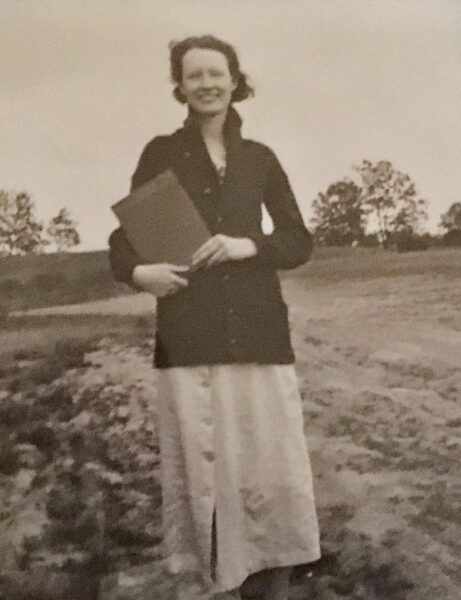

Mary E. Lunny on her 21st birthday, in 1934, in a photo taken by her future husband, Clark Norton. Courtesy Mary Beth Norton

My maternal grandparents were both immigrants from Ireland, but they arrived in the United States under different circumstances. Margaret Jane (Jennie) Stephenson was brought by her parents from County Monaghan in 1879, when she was three. Her eventual husband, Richard Lunny, one of nine children, emigrated alone from County Fermanagh in 1890 at the age of 22, following an older brother. The two ended up in Ann Arbor, Michigan, where they married in 1912. My mother was born the following year.

The family struggled throughout my mother’s childhood and youth. Richard was an uneducated laborer, partly disabled from a fall at work, but with a green thumb that he put to work by growing vegetables and berries that my mother peddled. Meanwhile, my grandmother took in boarders and the family also “flipped” houses—they lived in them, fixed them up, then sold them while buying another. There was no money for extras, including books; neighbors, recognizing that Mary loved to read, occasionally purchased books for her, some of which she treasured for the rest of her life.

My mother and I became professional academics in the same years of the late 1960s (when I was in graduate school) and the 1970s.

She would never have been able to afford college had she not been able to live at home. Enrolled at the University of Michigan during the Depression, she majored in history, with a minor in classics; she loved Latin. She must have been a remarkable student, as she graduated Phi Beta Kappa with a straight-A average. Her highest aspiration was to become a high school teacher, and after graduation in 1935, she started teaching in a nearby town, commuting home on weekends to help her father, a widower after her mother’s death from cancer that year, and her younger sister. She also earned an MA in history at Michigan in the summers.

Meanwhile, in college she met the man she would marry, my father, Clark Norton. They were engaged for five years, since he could not support her on his teaching fellowship while he earned a PhD, and she would have lost her job had she married, because of the Depression-era state law that forbade married women to hold publicly funded jobs. They therefore married after he earned his degree. Their honeymoon was a drive to his first teaching job, at the University of Montana in Missoula, where he taught multiple courses in a combined history-political science department. She spent many hours writing the lectures he would give a few days later; otherwise he could not have kept up with all the classes.

In 1942, they moved back to Michigan to be close to their families, and my younger brother and I were both born in Ann Arbor while my father taught political science at the university. In 1948, he moved to DePauw University in Greencastle, Indiana, where we were raised and where my mother became the quintessential 1950s housewife, participating in a sewing circle with other faculty wives, teaching Sunday school, and volunteering with the local League of Women Voters, of which she served as president for a time. (Born before American women had the right to vote, she voted regularly throughout her life, including in a primary just two months before her death, when she was in failing health.) After my brother entered junior high, she renewed her teaching credentials and again taught high school for a year but found the job unsatisfactory. Fortunately, a neighbor of ours was the chair of the classics department at DePauw and needed someone to teach introductory Latin. Knowing my mother’s training in college, he hired her . . . and that was the beginning of a dramatic change in her life, as she then continued to teach Latin courses at DePauw.

I once asked her if she regretted not studying for a PhD. She replied that she wished one of her professors had suggested such an option.

A few years later my father, who had been active in Democratic Party politics in Indiana, was offered the position of legislative assistant to Birch Bayh, then in his second year in the US Senate. My parents accordingly moved to the Washington area. My father shopped my mother’s résumé around to local colleges, and George Washington University hired her as a lecturer in the classics department. For the next 20 years, she taught a variety of courses there, primarily part time but occasionally full time. Starting with Latin language and literature (at both beginning and advanced levels), she moved on to teach courses on such subjects as classical civilization, Latin word origins, and women in antiquity, among others.

What that meant was that my mother and I became professional academics in the same years of the late 1960s (when I was in graduate school) and especially the 1970s. We both developed courses on women’s history, and we once were invited to give a joint presentation at a college where a friend of mine was on the faculty, which we both greatly enjoyed. She won a Fulbright to study one summer at the American Academy in Rome; she wrote articles for various publications in the field of classics; and she compiled a comprehensive bibliography on classics teaching. She loved teaching at the university level, and her students adored her. When she retired, she was honored at a GWU commencement ceremony, which I think was unprecedented for a non-tenure-track lecturer. But she was always underpaid, like all adjuncts.

I once asked her if she regretted not studying for a PhD. She replied that she did not regret the life she had led but wished that one of her professors at Michigan in the 1930s had suggested such an option to her. When I was at my parents’ house during one semester break in the 1970s, I found her crying while reading job ads for beginning classics professors. “I just wish someone had told me I had a choice,” she told me. As the daughter of a poor immigrant family, earning a PhD was a goal she simply could not envision for herself. She thought that if someone had mentioned that idea to her, at least she could have considered it, whether she had followed up on the suggestion or not. I probably need not add that she and my father both encouraged me to earn a PhD, at a time in the mid-1960s when attitudes had changed only slightly from those she encountered, and that my own career path owes a great deal to that encouragement.

As a longtime professor of women’s history, I think of my mother’s life as emblematic of those of so many other women of her generation. She had a good life, one that began in poverty and ended as solidly middle class, but it was also one of missed opportunities. I think of the standout student she must have been in the 1930s and deeply resent the sexism that prevented her professors from urging her to continue her education. She remained intellectually alert and engaged till near the end of her life; even after she reached 100, she avidly surfed the web and kept in touch with friends and relatives via email. In 2017, she was one of the women featured in Sarah Bunin Benor and Tom Fields-Meyer’s We the Resilient: Wisdom for America from Women Born Before Suffrage (Luminare Press). And that is the correct word to describe her: resilient.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.