I stand on a narrow gravel beach on the northern shore of a lake in a wondrous national park often claimed to be the world’s first. The lake is the largest in North America at such an elevation, 7,730 feet above sea level, and its southern end is beyond sight. To my left, east-southeast, is a range of snow-capped peaks. The sky is blue, the water is crystal clear and as placid as glass, and as my eyes sweep westward, they take in a long, dark strip of lodgepole pine forest that stretches across the horizon.

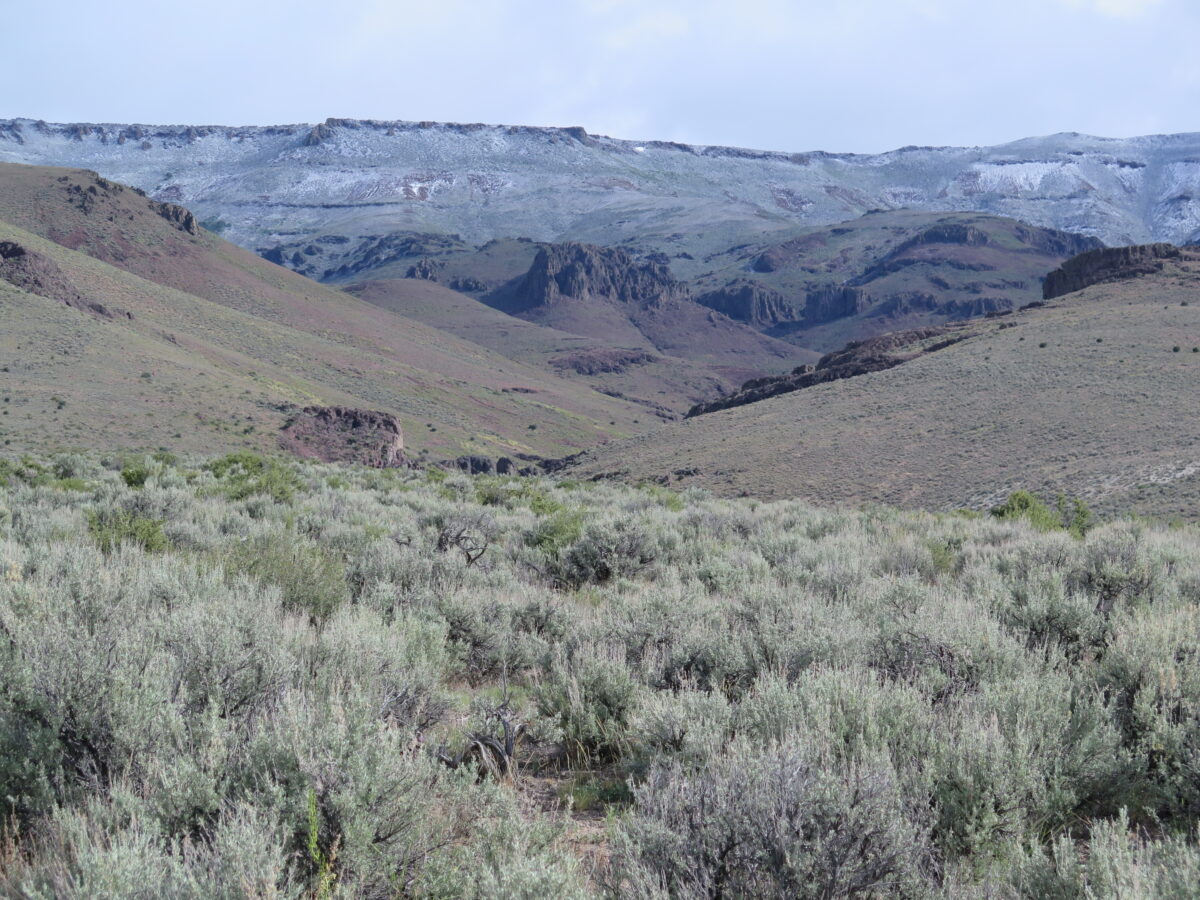

The Yellowstone magma plume, hot spot, and plate tectonics created a geological Greater Yellowstone that connects distant ancient landscapes to today’s national park, including the McDermitt Caldera Rim, pictured here. Mark Fiege

I have been visiting Yellowstone National Park for 60 years, reminded every time of my smallness, my irrelevance, in the face of almost unimaginable spans of time and distance. As spectacular as it is, however, the lake vista obscures a perspective that dramatically enlarges Yellowstone’s historical significance. To find the full story, I must turn my back on the lake’s breathtaking beauty and look in the opposite direction.

At Yellowstone or any national park—and indeed any place on Earth—landscape features that are hidden, small, subtle, obscure, or common often reveal more than those that instantly catch the eye. The significance of geysers, waterfalls, wolves, bison, and the lake is self-evident to most visitors; Yellowstone’s icons evoke an instantaneous rush of wonder. But as a historian, I want to dig down and think harder to understand why things are the way they are. The reward is just as great, but it requires a little more effort. It requires me, a historian trained in textual methods and landscape studies, to recognize how deep history casts a long shadow over the recent past and the present.

Looking north from Yellowstone Lake, I see stretches of sand and gravel beaches rising from the shore that sit higher than the lake and higher than its water can reach in storms. Geologists call them “stranded beaches,” and they manifest an immense force without which Yellowstone National Park as we know it would not exist. About two miles beyond the beaches, a vast, irregular, extremely hot thermal plume of magma rises from deep within the Earth, swells the rocky crust, and pushes up a forested area some 800 feet higher than the lake and maybe 25 square miles in area. The thermal plume and its surface manifestation, the Yellowstone Hot Spot, create the Sour Creek Dome and cause the north end of the lake to tilt upward, leaving stretches of beach high and dry. Some 20 miles to the south of where I stand, the effect is the opposite, but just as astonishing. There the lake is tilting downward, its water submerging tree trunks on islands and along the shoreline. Although the tilt is happening in minute increments, it is ongoing, in real time.

It is impossible to overstate the causal power and historical significance of the Yellowstone Hot Spot and the volcanic caldera in which it sits. The hot spot is why Yellowstone National Park is so high, why so much precipitation falls there, why it has so many waterfalls and geysers, and why it was covered by a mile-deep cap of ice during periods of glaciation. That magnificent magma plume explains why the park is covered so thickly with highly flammable lodgepole pines and why it became a refuge for wolves, grizzlies, bison, pronghorn, and other wildlife. The beautiful and abundant landscape that the hot spot produced is why so many Native cultures visited the area, why Shoshone, Bannock, and Crow people called the place home, and why some Shoshone people once lived there year-round. It is why Yellowstone became a national park and not something else, like cattle ranches and westward moving migration routes. The hot spot, finally, puts into perspective the relatively recent story of Yellowstone’s “discovery” and the creation of the national park in 1872 and its subsequent history.

Indeed, the hot spot is the chief protagonist, the predominant more-than-human or other-than-human actor, in the formation of the park and areas well beyond it. It has inspired geologists to break free from neutral objectivity and the passive voice to write and speak with imagination and verve, as geologist Robert Smith did when he described the Yellowstone caldera as “a living, breathing caldera.” The hot spot calls to historians like me to see beyond shallow periodization and stereotyped icons to a deep past that expresses a profound struggle. Whenever I think of the hot spot’s staggering eruptive potential, I think of William Faulkner’s observation that the only subject “worth writing about” is “the human heart in conflict with itself.” The hot spot is Yellowstone’s beating heart, its animating force and its reason for being, the source of its immensely destructive power and its capacity for endless generative creation.

The hot spot is the chief protagonist, the predominant more-than-human or other-than-human actor, in the formation of the park and areas well beyond it.

Evidence for the Faulknerian drama of Yellowstone is everywhere, but recognizing it requires a geographical imagination that transcends the national park box and its “logo map,” as historian Daniel Immerwahr might call it, and expands upon the current popular and useful concept of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. An even greater “Greater Yellowstone” took shape over the past 16.5 million years from the encounter between the hot spot and the North American tectonic plate. As the giant plate crept west-southwest across the hot spot an inch or two every year, a huge underground magma chamber formed at the apex of the thermal plume. Eventually, the chamber built immense pressure and erupted with catastrophic force. As the plate inched onward, each successive caldera eventually became extinct, and the cycle of destruction and creation began again. The result over millions of years is a geologically and genealogically Greater Yellowstone consisting of a series of silent caldera groups (perhaps we might call them families), a record of ongoing death and rebirth, that extends hundreds of miles from Yellowstone National Park almost as far west as California.

McDermitt Caldera, which straddles the Oregon–Nevada line, is exemplary, and it once sat above the hot spot exactly where Yellowstone National Park is today. Although one of the oldest calderas at about 16.5 million years, it is strikingly similar to the most recent caldera within the national park, which dates back only some 640,000 years. The eruptions that formed them were virtually the same size. McDermitt once included a large freshwater body much like today’s Yellowstone Lake. And like the current Yellowstone, McDermitt was forested. In other respects, however, McDermitt is a relic of its former self. The lake and the forests are gone, as are the geysers and other steaming thermal features. Silent and austere, McDermitt today is a windswept place of rock, bunchgrass, and sagebrush—a kind of geological graveyard or mausoleum—bisected by shallow streams with a fauna that ranges from mule deer to rattlesnakes.

Yet an eerie similarity endures. Although heavily eroded, the jagged rock of the curving caldera rim still is evident along McDermitt’s northernmost extent. The significance of that rim occurred to me shortly after I returned from my exploration of McDermitt. I was in Yellowstone National Park and traveling south on the historic loop road. As I neared Madison Junction and the confluence of the Gibbon and Firehole rivers, the most intact portion of the 640,000-year-old curving caldera rim came into view. In an instant, despite the differences between the heavily eroded formation I had investigated at McDermitt and the relative youth and robust size of the one that now loomed above me, the similarities between the two seized my imagination. McDermitt Caldera is, at once, both the past and the future of our beloved Yellowstone National Park.

McDermitt Caldera once sat above the hot spot exactly where Yellowstone National Park is today.

The connections run deeper still, across time, distance, and experience. In the past, the US government systematically removed Native people from Yellowstone. Today, in an effort to reverse their exclusion, no fewer than 27 tribes claim historic ties to the park. A related act of colonial dispossession excluded Native people from McDermitt Caldera, now administered by the federal Bureau of Land Management. Confined to an adjacent reservation, the Fort McDermitt Paiute and Shoshone still claim the caldera as their homeland. At issue now between the federal government and corporations on one side and the Paiute and Shoshone people on the other is a natural element common to calderas that leaches from volcanic rock and accumulates at the bottom of ancient lakes: lithium. At Thacker Pass near the southern end of McDermitt, on land sacred to the Paiute and Shoshone, Lithium Americas in partnership with General Motors is mining the metal for batteries. No such mine is projected for Yellowstone National Park, but there have been proposals for gold mines on public lands to its north. And, of course, it is easy to imagine a moment soon when visitors arrive in the park in vehicles powered by batteries with lithium extracted from an ancestor caldera far to the west that is the homeland of its own Native people. Such are the connections—geological, cultural, economic, technological, political, historical—that give unity to an enlarged notion of Yellowstone.

In Searching for Yellowstone (1997), Paul Schullery wrote that the park is the site of “a great journey of discovery,” an endless “perceptual experiment” in which people continually shift their angle of vision and see ever more sides of nature’s infinite possibilities—and in seeing nature and the cosmos in that unconstrained way, recognize unlimited potential in themselves. Yellowstone is not a place of stasis. It is a landscape in motion, a dramatic, expansive, dynamic place of death but also of perpetual rebirth, a place in which the only limit is the boundaries—the walls, cages, and prisons—that people impose on their imaginations. Stand on the beach of an unspeakably beautiful lake, then look in the opposite direction and realize that the shining jewels on the surface of a great and wondrous national park are not the end of the quest, but only the beginning.

Mark Fiege recently retired as professor of history and the Wallace Stegner Chair in Western American Studies at Montana State University.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.